Jaded about education, more Americans are skipping college

JACKSON, Tenn. — When he looked to the future, Grayson Hart always saw a college degree. He was a good student at a good high school. He wanted to be an actor, or maybe a teacher. Growing up, he believed college was the only route to a good job, stability and a happy life.

The pandemic changed his mind.

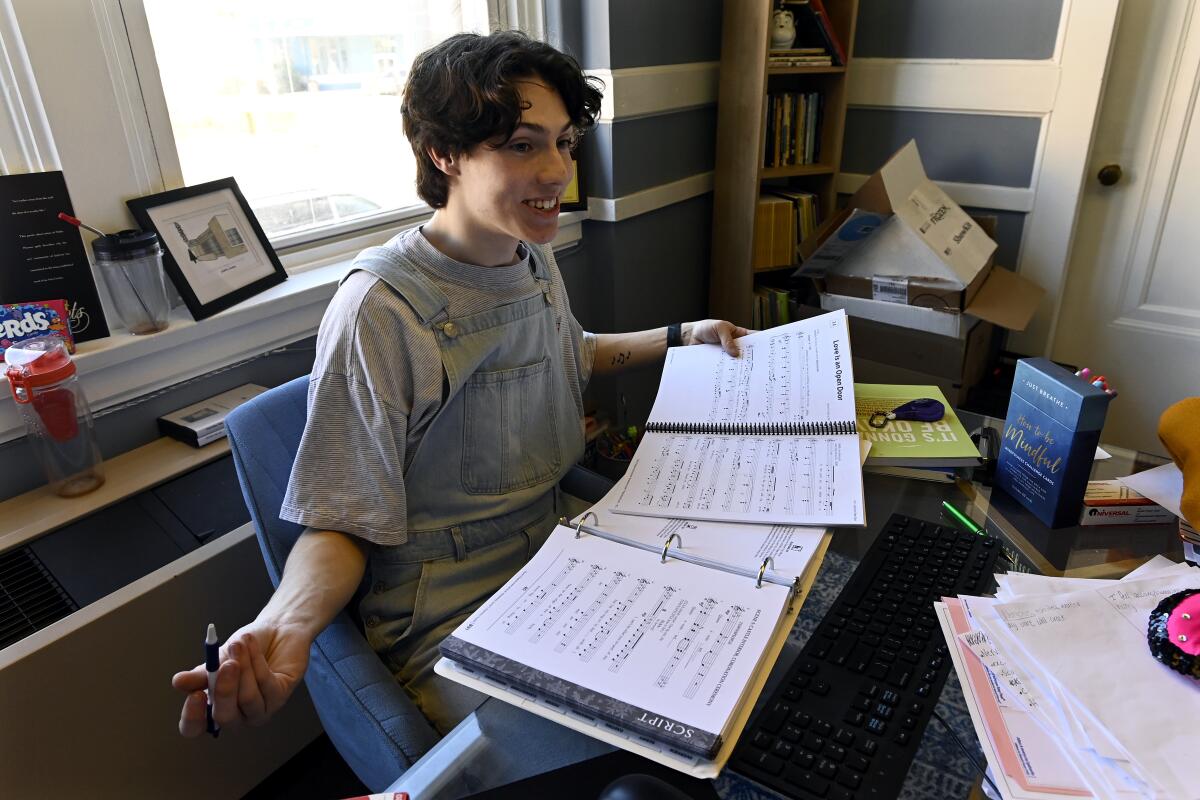

A year after high school, Hart is directing a youth theater program in Jackson, Tenn. He got into every college he applied to but turned them all down. Cost was a big factor, but a year of remote learning gave him the time and confidence to forge his own path.

“There were a lot of us with the pandemic, we kind of had a do-it-yourself kind of attitude of like, ‘Oh — I can figure this out,’” he said. “Why do I want to put in all the money to get a piece of paper that really isn’t going to help with what I’m doing right now?”

Hart is among hundreds of thousands of young people who came of age during the pandemic but didn’t go to college. Many have turned to hourly jobs or careers that don’t require a degree, while others have been deterred by the prospect of student debt.

What first looked like a pandemic blip has turned into a crisis. Nationwide, undergraduate college enrollment dropped 8% from 2019 to 2022, with declines even after returning to in-person classes, according to data from the National Student Clearinghouse.

With the high court expressing skepticism about Biden’s debt forgiveness, student loan borrowers are on notice that relief may not materialize.

Economists say the effect could be dire. At worst, it could signal a new generation with little faith in the value of a college degree. At minimum, it appears those who passed on college during the pandemic are opting out for good.

Fewer college graduates could worsen existing labor shortages. And for those who forgo college, it usually means significantly lower lifetime earnings, according to Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce.

In dozens of interviews with the Associated Press, educators, researchers and students described a generation jaded by education institutions. Largely on their own amid remote learning, many took part-time jobs. Some felt they weren’t learning anything, and the idea of further education held little appeal.

As a kid, Hart dreamed of going to Penn State to study musical theater. But when classes went online, he spent less time on coursework and more on creative outlets. He felt a new sense of independence, and the stress of school faded.

“I was like, ‘OK, what’s this thing that’s not on my back constantly?’” Hart said. “I kind of relaxed more in life and enjoyed life.”

He started working at a smoothie shop, and by the time he graduated, he had left college plans behind.

The shift has been stark in Jackson, where just four in 10 of the county’s public high school graduates immediately went to college in 2021, down from six in 10 in 2019.

It’s widely known from test scores that the pandemic set back students across the country.

Jackson’s leaders say young people are taking restaurant and retail jobs that pay more than ever. Some are being recruited by manufacturing companies that have raised wages to fill shortages.

America’s college-going rate was generally on the upswing until the pandemic reversed decades of progress. Rates fell despite economic upheaval, which typically drives more people into higher education.

In Tennessee, education officials issued a “call to action” after finding that 53% of public high school graduates in 2021 were enrolling in college, far below the national average. Other states are still collecting data on recent college rates, but early figures are troubling.

Most alarming are the figures for Black, Latino and low-income students, who saw the largest slides in many states. In Tennessee’s class of 2021, just 35% of Latino graduates and 44% of Black graduates enrolled in college, compared with 58% of their white peers.

After two years of record growth, the University of California received a smaller number of applications for fall 2023, led by drops in students from other states and countries.

Amid the chaos of the pandemic, many students fell through the cracks, said Scott Campbell, executive director of Persist Nashville, a nonprofit that offers college coaching. Many lost access to counselors and teachers who help navigate college applications.

In Jackson, Mia Woodard recalls struggling to fill out online college applications. No one from her school talked to her about the process, she said.

“None of them even mentioned anything college-wise to me,” said Woodard, who is biracial and transferred high schools to escape racist bullying.

She says she never heard back from the colleges. She wonders whether to blame her shaky Wi-Fi, or if she failed to provide the right information.

California’s ‘missing’ students may have moved away, be home-schooling without notifying the state, or simply be out of school.

A spokesperson for the Jackson school system, Greg Hammond, said it provides opportunities for students to gain exposure to higher education, including an annual college fair.

Hammond said school counselors provide additional support for at-risk students like Woodard. “It is, however, difficult to provide post-secondary planning and assistance to students who don’t participate in these services,” he said.

Woodard now works at a restaurant and lives with her dad. Maybe one day she’ll pursue her dream of getting a culinary arts degree.

“It’s still kind of 50-50,” she said of her chances.

If there’s a bright spot, experts say it’s that more young people are pursuing education programs other than a four-year degree. Some states are seeing growing demand for apprenticeships in the trades.

Both 529 plans and I Series Savings Bonds have advantages when saving for education. But for most families, here is why 529 plans have the edge.

Before the pandemic, Boone Williams was the type of student colleges compete for. But when his school outside Nashville sent students home his junior year, he spent his days working at local farms.

When a family friend told him about union apprenticeships, he knew it was what he wanted. Today he works for a plumbing company and takes night classes at a union.

Eventually he expects to earn far more than friends who took quick jobs after high school.

“In the long run, I’m going to be way more set than any of them,” the 20-year-old said.

Back in Jackson, Hart wonders what’s next. His pay provides enough for stability but not a whole lot more. He still thinks about Broadway, but doesn’t have a clear plan for the next 10 years.

“I do worry about the future and what that may look like for me,” he said. “But right now I’m trying to remind myself that I am good where I’m at, and we’ll take it one step at a time.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.