Nicaragua frees 222 political prisoners, sends them to U.S.

MEXICO CITY — Nicaragua’s authoritarian government freed 222 political prisoners and sent them to the United States on Thursday in a surprise move that appears aimed at easing stinging U.S. economic sanctions.

The former prisoners, some of whom spent years in jail, landed at Washington’s Dulles International Airport, where a crowd of tearful friends and family members waited, clutching blue and white Nicaraguan flags.

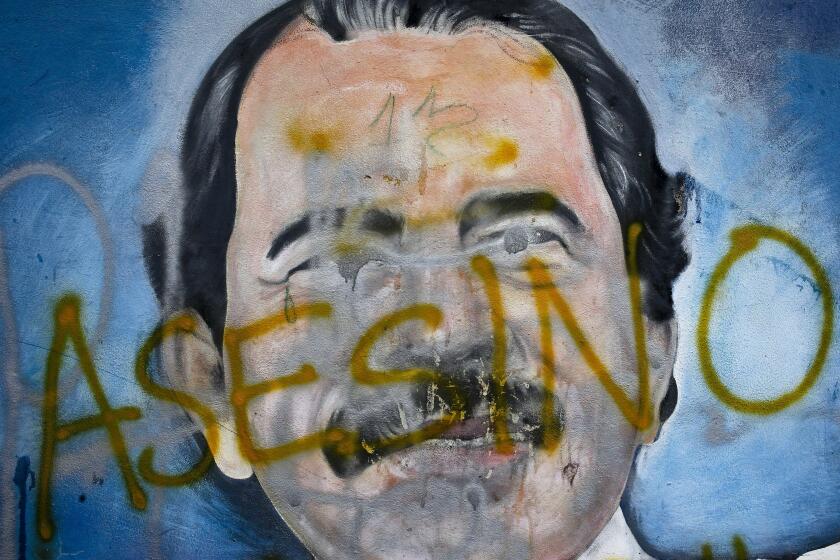

The prisoner release was a stunning turn of events for Nicaragua, which has been punished by stiff sanctions after its ruler, former Sandinista revolutionary Daniel Ortega, rigged elections, violently repressed protests and jailed hundreds of critics, including business and religious leaders, activists, journalists and presidential candidates.

The release was a “unilateral” action taken by Ortega, U.S. officials said, but it came after a lengthy campaign of public and private pressure on his government from Washington, the Vatican and countries across Latin America. U.S. officials said they promised nothing concrete in exchange for the release but praised the move for its potential to improve relations with Managua, with Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken deeming the release “a constructive step” that “opens the door to further dialogue between the United States and Nicaragua.”

News of the release was celebrated worldwide, yet for many Nicaraguans it was bittersweet.

“The political prisoners ... were put on a chartered plane and sent into exile at dawn in the same arbitrary manner in which they were detained,” wrote famed writer and former Ortega ally Sergio Ramírez in a column in El País newspaper. Their release, he said, is a “small joy” for a country “that has not yet awakened from its long nightmare.”

Hours after the prisoners were released, the country’s legislature declared them “traitors to the nation” and modified the constitution to strip them of their citizenship.

The prospect that the United States and Nicaragua could be inching toward rapprochement speaks not just to the severity of the sanctions in Nicaragua, already one of the poorest countries in the region, but also to a strategic shift by the Biden administration, which has shown new willingness to engage with Latin American autocracies long blacklisted by the U.S.

The prisoner release, which Blinken atrributed to “concerted American diplomacy,” represents the Biden administration’s latest engagement, however limited, with three socialist nations — Nicaragua, Cuba and Venezuela — that John Bolton, former national security advisor under President Trump, once labeled the “troika of tyranny.”

In Venezuela, the Biden White House has ditched the confrontational approach of the Trump administration, which fruitlessly sought to overthrow the government of Nicolás Maduro, and last year sent a high-level delegation to negotiate the release of several U.S. citizens detained there. Nine were eventually freed, and Maduro’s government agreed to renew talks with the opposition. In exchange, the U.S. slightly eased sanctions to allow energy giant Chevron to resume oil production in Venezuela, which is home to some of the world’s largest petroleum reserves.

Also last year, Washington relaxed some sanctions against communist-run Cuba, which has been the target of a six-decade U.S. trade embargo. Among other steps, the Biden administration agreed to bolster consular services in Havana, expand authorized travel to the island and increase limits on family remittances sent to Cuba.

Whether any sanctions relief will be forthcoming for Nicaragua remains to be seen.

The sanctions have targeted Ortega and his family, many of their backers and key industries including sugar production and gold mining.

The country’s economic situation has become more precarious as one of its longtime backers — Russia — has been sapped by war in Ukraine and sanctions of its own.

Analysts said that while relaxing sanctions is of critical importance to Ortega, his motives may be more complex: Ortega may have decided that it is advantageous to have his most vocal opponents out of the country and disenfranchised.

“It’s hard to read Ortega’s mind,” said Michael Shifter, senior fellow at the Inter-American Dialogue, a Washington think tank, who has tracked Central America for decades. “Perhaps he acted now because the costs of keeping these prisoners, with the chance that more would die, outweighed the benefits.”

With virtually no independent journalists left inside and foreign reporters banned from entering, Nicaragua has become ‘an information black hole.’

A former leader of the leftist Sandinista rebels, Ortega helped overthrow the country’s right-wing dictatorship in 1979.

He first served as president in the 1980s during a civil war that pitted Sandinista fighters against U.S.-backed Contra rebels. He was voted out in the 1990 presidential election but returned to power in 2007. By manipulating elections, he has remained president ever since, becoming the longest-serving leader in Latin America.

After violently suppressing pro-democracy protests in 2018, Ortega and his wife, Vice President Rosario Murillo, cracked down further, imprisoning hundreds of people whom they derided as “coup plotters,” “terrorists” and “termites.”

Those jailed in recent years include presidential candidate Miguel Mora, two adult children of former President Violeta Chamorro and several Catholic priests. They also include some of Ortega’s former leftist comrades, among them Dora María Téllez, a Sandinista commander who accused Ortega of betraying the revolution’s promise of a socialist utopia and coming to resemble the dictator they once helped overthrow.

Many were jailed at Managua’s infamous El Chipote prison, where, according to people imprisoned there, torture was common and food and medical care was scant. At least one political prisoner, 77-year-old former Sandinista leader Hugo Torres, died while in custody.

News of a possible surprise release began circulating on Wednesday night.

Dolly Mora, a 30-year-old leader of the Nicaraguan University Alliance, a political youth movement, said she began hearing reports that inmates were being moved out of various prisons.

The Inter-American Human Rights Court has declared the government of Nicaragua in contempt of court for ignoring rulings on political prisoners.

She was so excited she didn’t sleep. The group that landed in Washington included four people from her university group who had been sentenced to years in prison, including for violating a sweeping treason law, she said.

“We are happy that our friends and all the prisoners are going to be free,” said Mora, who left Nicaragua last year — one of hundreds of thousands of people who have fled the country — and is living in the United States.

But she added: “This is not over. They freed the prisoners, but there’s still the fight for freedom in Nicaragua.”

Luis Carrillo, a Colombian priest who was forced to leave Nicaragua in 2020 after he had his permanent residency revoked for speaking out against the government, said the country’s decision to strip the former prisoners of their nationality suggests there is a long road ahead in the quest of restoring the country’s democracy.

“Simply for not thinking like them and not agreeing with all the barbarities and Machiavellian atrocities, today they are practically exiled,” he said of the released prisoners.

“I’m very grateful to the United States for receiving them,” he said. “But it also hurts a lot.”

Linthicum, McDonnell and Miller reported from Mexico City and Wilkinson from Washington.

The Inter-American Human Rights Court has declared the government of Nicaragua in contempt of court for ignoring rulings on political prisoners.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.