MEXICO CITY — Luis Rodríguez spends three hours on the subway most days traveling between his home on the northern edge of Mexico City and his university 25 miles south.

It’s a long commute for the 21-year-old student. His mother hates every minute of it.

Like the rest of the country, she’s watched as the aging subway system here has been crippled by deadly accidents, including a collapse in 2021 that killed 26 people and a collision this month that left an 18-year-old student dead.

“She tells me to be very safe, but the truth is, it’s out of our hands,” Rodríguez said as he steadied himself on a shuttering subway car on a recent morning. “It’s not up to me whether this line collapses. We’re all vulnerable here.”

The inauguration of the Mexico City Metro shortly after the 1968 Olympics was supposed to modernize this bustling mountain capital, bringing it on par with great world cities such as Paris and New York.

It promised too to be a great equalizer, giving the millions of workers living in informal settlements on the city’s periphery access to the thriving culture and economy at its center.

An overpass of the Mexico City Metro collapsed, sending a train crashing onto the road below, trapping cars and killing at least 24 people.

But after years of neglect, the Metro has instead become a stand-in for Mexico’s broader problems: entrenched inequality, unreliable public services and corruption so flagrant and pervasive that at times it actually kills.

These days, the Metro is also a political battlefield.

In addition to the deadly crashes, other alarming incidents in recent months include electrical failures, train cars spontaneously separating and a series of underground fires that have sickened dozens of riders. On Monday, 18 people were hospitalized after high-voltage cables overheated and choked a station with black smoke.

Opponents of Mexico City Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum — a favorite to become the country’s next president — blame her for the breakdowns, saying her government has not properly maintained the system.

Despite spiraling violence and a stagnating economy, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has maintained sky-high approval ratings because he speaks to the working poor.

Sheinbaum, in turn, has blamed unnamed saboteurs for what she describes as an “atypical” uptick in system failures.

She is backed by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a longtime political ally who granted her request to deploy more than 6,000 national guard troops to the Metro to ward against what he termed — without offering evidence — possible “premeditated” attacks.

Critics say the government should be sending engineers, not soldiers, to address the Metro’s problems. During a series of protests in recent days, activists scrawled graffiti linking the troop deployment to López Obrador’s broader militarization of the country and calling Sheinbaum an “assassin.”

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s election in Brazil is the latest triumph for the left, which now controls six of Latin America’s seven largest countries.

As prosecutors investigate the recent incidents, one thing is clear: The crashes, political discord and now troops in fatigues at every train station have unnerved many of the 5 million mostly working-class people who rely on the Metro daily.

“None of us are comfortable,” said Armando, a 72-year-old textile vendor who declined to give his last name precisely because the Metro has become so politicized. “But we suffer it anyway because there is no other option.”

For the 22 million people who live in and around Mexico City, an unruly metropolitan area that spans 3,000 square miles, transportation has always been a thorny issue.

Many can’t afford cars, and anyway, roads and highways are notoriously snarled with traffic. Privately run buses are ubiquitous but frequently targeted by armed robbers.

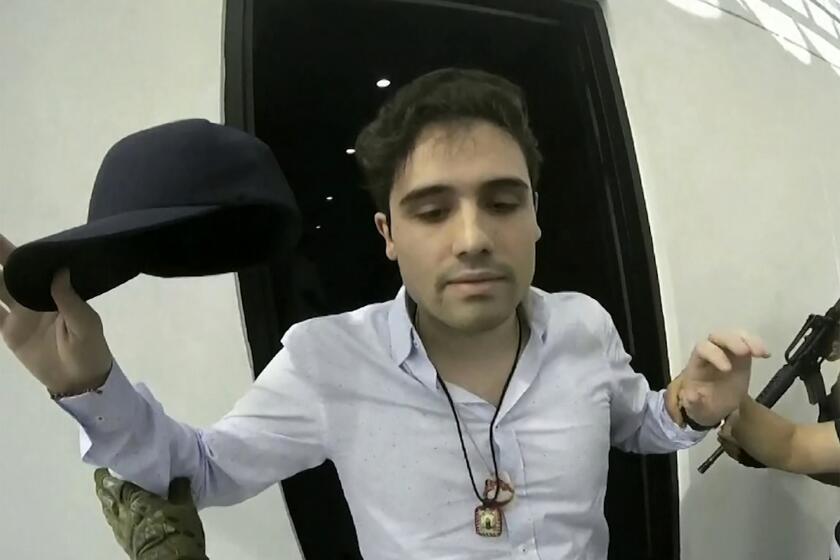

In Mexico stronghold of Sinaloa cartel, armed men burn vehicles, storm airport to try to prevent capture of drug lord Joaquín ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán’s son.

The Metro, with its 140 miles of underground and elevated tracks, has long been the most efficient and inexpensive way to get around. It is a city in itself: a labyrinth of echoing corridors and 195 stations boasting internet cafes, dress shops, pizza places, libraries and even yoga classes.

A ride costs just 5 pesos — around 25 cents — and is heavily subsidized by the government. That cheap fare is part of the problem: The system has never come close to paying its own costs, so maintenance depends on how much money political leaders allot it. Until 2021, funding for the Metro had steadily fallen, part of a broader austerity plan pushed by López Obrador.

The disrepair is obvious. On some lines, train cars that debuted when the Metro opened 54 years ago are still in use. Stations are poorly lighted, and many escalators are perpetually broken, so old that replacement parts are no longer manufactured.

“A lot of equipment and systems have already exceeded their useful lifespan and should have been replaced 20 years or 15 years ago,” said Jorge Jiménez Alcaraz, who heads Mexico’s trade group for engineers and architects and who served as the director of the Metro system in 2018. He said that he and other Metro officials frequently asked for more resources, but that politicians were loath to raise train fares because of the protest it would provoke.

Although the Metro has long been beset by pickpocketing and sexual harassment — so much so that a few years ago the city began segregating train cars by gender and handing out rape whistles — its safety problems have come into focus more recently, spurred in part by a string of dramatic wrecks.

In 2020, two trains collided, killing one person and injuring 41 others.

The following year, a fire in a Metro control center killed one and injured 31.

Later in 2021, an elevated train line buckled in half, dragging two subway cars onto the highway below. The crash on Line 12 killed 26 people, injured 100 and made the Metro’s failings global news.

As soon as that line had been inaugurated in 2012, passengers had begun complaining about cracks in the structure of the concrete viaduct over which the trains passed. A congressional investigation in 2014 found major structural flaws, low-quality construction materials and a “deficient, hasty and incomplete certification of the functionality and safety of the line.”

A Norwegian firm hired to investigate the accident blamed faulty construction and a lack of maintenance under Sheinbaum, who took office in late 2018, and the previous mayoral administration. Sheinbaum rejected the findings and threatened to sue the firm.

The political ramifications were immediate. The section of train line that collapsed had been built by a company owned by Mexico’s wealthiest man, telecom and construction magnate Carlos Slim, during the mayoral term of Marcelo Ebrard, now foreign secretary and Sheinbaum’s top rival for the presidential nomination of their political party, Morena.

After the crash, protesters demanded more investment in the Metro: “It wasn’t an accident, it was negligence,” read messages written around the city.

Sheinbaum promised to rebuild Line 12 and make other improvements.

But the problems have continued. This month, two trains collided, killing one person and injuring 57.

There are signs the incidents are damaging the mayor’s political standing.

As President Biden visits El Paso, thousands of people who fled oppressive countries are marooned in Mexico in the wake of his expansion of a Trump-era policy.

A January poll by El Financiero newspaper showed support for Sheinbaum had dipped in one month by 5 percentage points to 41%.

Her opponents say the sabotage allegations are attempts to shift blame.

“She is incapable of understanding the criminal responsibility that she bears for the unfortunate death of people on the Metro during her government,” said Luisa Gutiérrez, a local deputy for the right-of-center National Action Party.

Riders themselves are worried but resigned. Chilangos, as Mexico City residents call themselves, are used to living with the unknown: major earthquakes, unexpected water shortages, electrical blackouts.

“We’re resilient people,” said Miguel Ángel Sanchez, 69, who was waiting in a crush of morning rush-hour commuters, hoping to board a train. As usual, there were long delays. Earlier, another train he had been riding on had stopped on the tracks for several minutes, not moving, as the smell of smoke filled the tunnel.

He said he wished the politicians deciding the fate of the Metro actually rode it.

“Which among them would get on the Metro?” he asked. “No, they all have high-end cars: Mercedes, BMWs, Audis.”

In front of him, people pushed onto an already crowded waiting train. One man’s backpack got caught between the doors and other passengers scrambled to free it. Sanchez looked on in disgust. “Look at this,” he said. “It makes me want to move to the country.”

Cecilia Sánchez Vidal in The Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.