After difficulties with injection, Alabama cancels execution greenlighted by Supreme Court

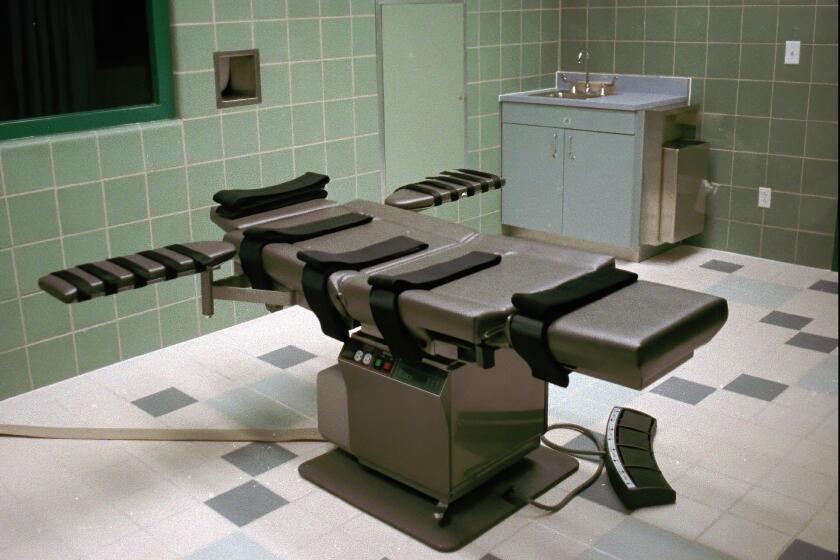

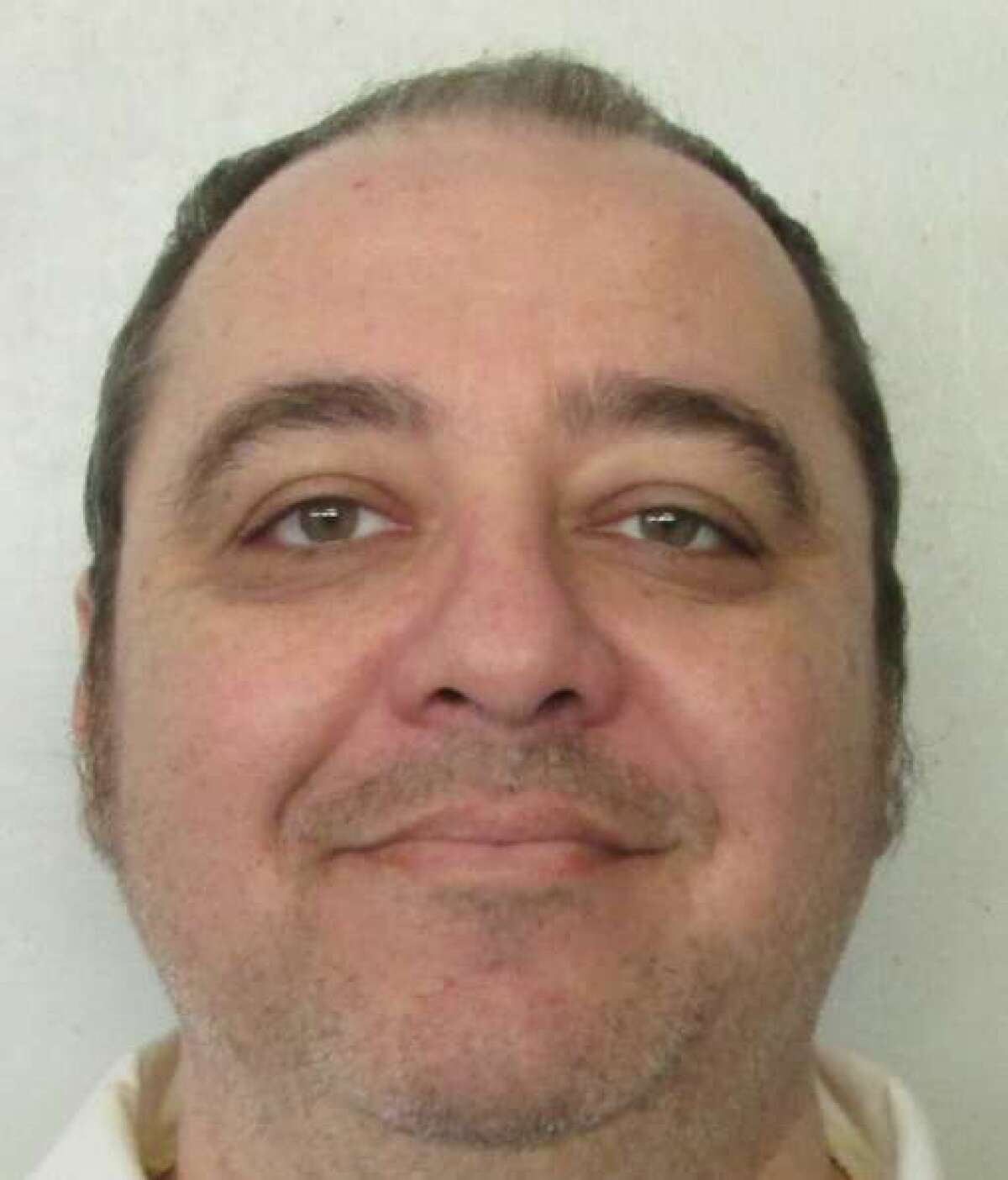

ATMORE, Ala. — Alabama’s execution of a man convicted in the 1988 murder-for-hire slaying of a preacher’s wife was called off Thursday just before the midnight deadline because state officials couldn’t find a suitable vein in which to inject the lethal drugs.

Alabama Department of Corrections Commissioner John Hamm said prison staff tried for about an hour to get the two required intravenous lines connected to Kenneth Eugene Smith, 57. Hamm said they established one line but were unsuccessful with a second line after trying several locations on Smith’s body. Officials then tried a central line, which involves a catheter placed into a large vein.

“We were not able to have time to complete that, so we called off the execution,” Hamm said.

It is the second execution since September that the state has canceled because of difficulties with establishing an IV line with a deadline looming.

The Supreme Court had cleared the way for Smith’s execution when, about 10:20 p.m., it lifted a stay issued earlier in the evening by the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. But the state decided about an hour later that the lethal injection would not happen that night.

The postponement came after Smith’s final appeals, which had focused on problems with intravenous lines at Alabama’s last two scheduled lethal injections. Because the death warrant expired at midnight, the state must go back to court to seek a new execution date. Smith was returned to his regular cell on death row, a prison spokesperson said.

The drop in the number of executions this year was due in part to the pandemic but also came during a decline in support for the death penalty.

Prosecutors said Smith was one of two men who were each paid $1,000 to kill Elizabeth Sennett on behalf of her husband, who was deeply in debt and wanted to collect on insurance. The slaying, and the revelations over who was behind it, rocked the small north Alabama community.

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey blamed Smith’s last-minute appeals for the execution not going forward as scheduled.

“Kenneth Eugene Smith chose $1,000 over the life of Elizabeth Dorlene Sennett, and he was guilty, no question about it. Some three decades ago, a promise was made to Elizabeth’s family that justice would be served through a lawfully imposed death sentence,” Ivey said. “Although that justice could not be carried out tonight because of last-minute legal attempts to delay or cancel the execution, attempting it was the right thing to do.”

Alabama has faced scrutiny over its problems with recent lethal injections. In ongoing litigation, lawyers for inmates are seeking information about the qualifications of the execution team members responsible for connecting the lines. In a Thursday hearing in Smith’s case, a federal judge asked the state how long was too long to try to establish a line, noting that at least one state sets an hour limit.

A lethal injection testing oversight prompted Tennessee’s governor to call off the execution of convicted killer Oscar Smith an hour beforehand.

The execution of Joe Nathan James Jr. took several hours to get underway because of problems establishing an IV line, leading an anti-death penalty group to claim the execution was botched.

In September, the state called off the scheduled execution of Alan Miller because of difficulty accessing his veins. Miller said in a court filing that prison staff poked him with needles for more than an hour, and at one point they left him hanging vertically on a gurney before announcing they were stopping. Prison officials have maintained that the delays were the result of the state carefully following procedures.

Sennett was found dead March 18, 1988, in the home she shared with her husband in Alabama’s Colbert County. The coroner testified that the 45-year-old woman had been stabbed eight times in the chest and once on each side of the neck. Her husband, Charles Sennett Sr., who was the pastor of the Westside Church of Christ, killed himself when the murder investigation focused on him as a suspect, according to court documents.

John Forrest Parker, the other man convicted in the slaying, was executed in 2010. “I’m sorry. I don’t ever expect you to forgive me. I really am sorry,” Parker said to the victim’s sons before he was put to death.

Breaking News

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

According to appellate court documents, Smith told police in a statement that it was “agreed for John and I to do the murder” and that he took items from the house to make it look like a burglary. Smith’s defense at trial said he had participated in the attack but had not intended to kill her, according to court documents.

In the hours before the execution was scheduled to be carried out, the prison system said Smith visited with his attorney and family members, including his wife. He ate cheese curls and drank water, but declined the prison breakfast offered to him.

Smith was initially convicted in 1989, and a jury voted 10-2 to recommend a death sentence, which a judge imposed. His conviction was overturned on appeal in 1992. He was retried and convicted again in 1996. The jury recommended a life sentence by a vote of 11-1, but a judge overrode the recommendation and sentenced Smith to death.

In 2017, Alabama became the last state to abolish the practice of letting judges override a jury’s sentencing recommendation in death penalty cases, but the change was not retroactive and therefore did not affect death row prisoners like Smith. The Equal Justice Initiative, an Alabama-based nonprofit that advocates for inmates, said Smith stands to become the first state prisoner to be executed through judicial override since the practice was abolished.

The Supreme Court on Wednesday denied Smith’s request to review the constitutionality of his death sentence on those grounds.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.