LONDON — Britain bade its final farewell to Queen Elizabeth II on Monday, honoring its longest-reigning monarch with a state funeral that provided pomp in solemn circumstances, drew dignitaries from around the world and captivated a global television audience.

The hourlong event inside Westminster Abbey, a service attended by 2,000 people and which reflected the Old World grandeur of Britain’s monarchy, followed 11 days of national mourning and highly choreographed public ceremonies.

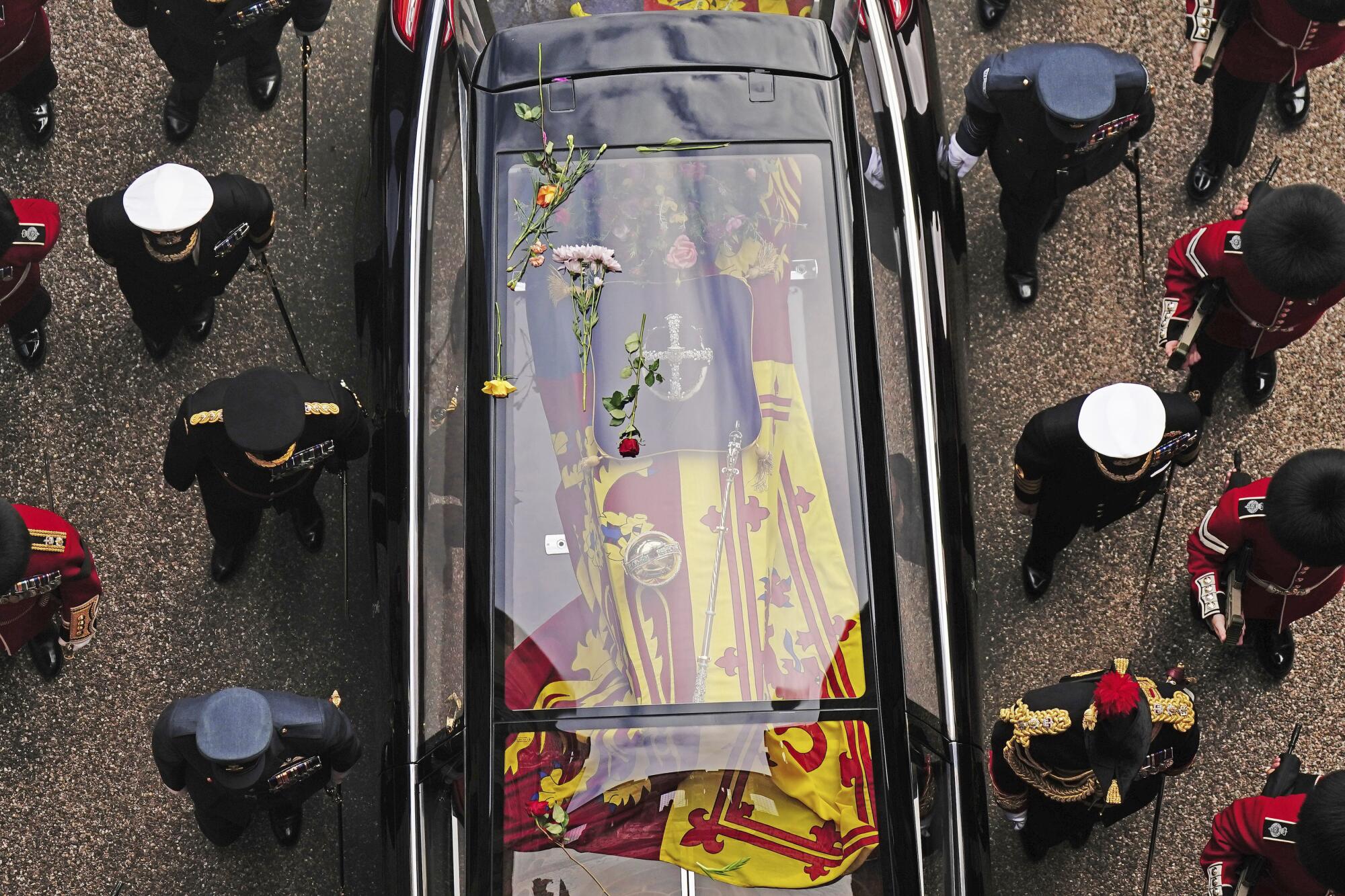

Afterward, the queen’s coffin, topped by symbols of state, made its slow procession through the streets of London on its way to St. George’s Chapel in Windsor Castle, where it was lowered into the royal vault ahead of a more intimate interment ceremony involving King Charles III and other royal family members, which officials described as a “deeply personal family occasion” that would be held without media coverage.

The ceremony at St. George’s, a committal service with 800 people, was the last in a series of public events commemorating a figure whose life many felt served as the very model of a modern major monarch. Dean of Windsor David John Conner opened with a nod to the stoicism and stiff-upper-lip ethos the queen appeared to embody for many of her subjects.

“In the midst of our rapidly changing and frequently troubled world, her calm and dignified presence has given us confidence to face the future, as she did, with courage and with hope,” he said.

Then followed moments steeped in the symbolism of the royal transfer of power: The lord chamberlain, the top official in the queen’s household, broke his wand of office, which was buried with the late monarch to indicate the end of his service. Later, the crown jeweler took the diamond-encrusted imperial state crown, the orb and scepter from atop the queen’s coffin and passed them to Conner to place on the altar. Her casket was lowered to the strains of a lament from the queen’s bagpiper.

When the national anthem played, crowds gathered outside Windsor stood as one. Along the tree-lined avenue leading to Windsor Castle known as the Long Walk, more than 100 police officers in traditional black-and-white uniforms took up positions to keep the peace.

Earlier in London, tens of thousands of people streamed to the environs of Buckingham Palace, hoping to catch a glimpse of the cortege on its route and to pay their final respects.

“She’s just been a part of our lives forever,” said Angie Judge, who along with her sister, Maureen, had woken up before daybreak to make sure to nab spots in Hyde Park to watch the funeral on a giant screen. Both women wore crisp white T-shirts with the words “Forever in our hearts” printed above a portrait of the queen.

“It’s not going to be the same ever again. I love Charles, but I can’t say ‘God save the king’ yet,” Judge said, referring to the new King Charles III.

Before her death Sept. 8, Elizabeth reigned for a record-breaking 70-year span that saw Britain emerge from the ashes of World War II and eventually enter the digital age. Before the funeral began Monday morning, Westminster Abbey’s largest bell tolled once a minute for 96 minutes to mark each year of the late monarch’s life.

Queen Elizabeth II’s state funeral draws presidents and kings, princes and prime ministers — and crowds of mourners in the streets of London.

Her casket, which had lain in state in the Houses of Parliament for more than four days for hundreds of thousands of mourners to file past, was drawn on a gun carriage by an honor guard to the abbey, the ancient church where Elizabeth was married in 1947 and crowned in 1953. Among those walking behind the carriage were Charles, his sister and two brothers, and his two sons, Harry and William, who is now first in line to the throne.

Eight pallbearers from the Queen’s Company 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards took the coffin inside for the service, which began at exactly 11 a.m. when David Hoyle, the dean of the abbey, exhorted congregants to pray in “a church where remembrance and hope are sacred duties.”

The attendees included the royal family, President Biden and First Lady Jill Biden, the kings of Spain and Belgium, emirs from the Middle East, other government heads and selected members of the British public, most of them having known no other sovereign but Elizabeth.

“With gratitude we remember her unswerving commitment to a high calling over so many years as queen and head of the Commonwealth,” Hoyle said. “With admiration we recall her lifelong sense of duty and dedication to her people. With affection we recall her love for her family and her commitment to the causes she held dear.”

Outside, some people had lined up overnight to gain entry to designated viewing areas, which by 10 a.m. had filled to capacity, with police sealing entry from the Mall, the wide boulevard leading from Buckingham Palace, and directing the endless flow of people to Hyde Park. Street vendors made brisk business selling all things Britannia, including hats, shawls, flags and other knickknacks featuring the Union Jack.

Barring tragedy or revolution, Britain is set to have a man instead of a woman on the throne for the next 75 years at least.

When the congregation inside Westminster Abbey stood for the first hymn, the entire crowd in Hyde Park also rose up from their blankets and lawn chairs, and remained standing until the singing finished. One of two Scripture readings was delivered by Liz Truss, the British prime minister, whom the queen formally appointed to the post just two days before her death, in a reflection of the sense of duty that endeared her to her subjects throughout the United Kingdom.

“She just summed up what the country was and what it means to be British,” said Dan Schofield, who came from outside London with his wife and their two daughters. “We just wanted to pay our respects and for our kids, when they’re older, to be able to say they were here.”

But not all Britons shared equally in the moment. Many went about their daily business or found other ways to enjoy the unexpected public holiday.

Tina Thorpe, a Londoner, said the wall-to-wall coverage by the British media over the last week was too much.

“I think it’s going overboard,” said Thorpe, 62. “It’s interesting, but I don’t like the endless royal commentary. We are being told how to mourn.”

Thorpe said she enjoyed celebrating the queen’s Platinum Jubilee in the summer and organized a street party, but that was more about the community coming together. The queen’s death has elbowed aside news of anything else.

“What is going on in Pakistan? What’s going on in the rest of the world? What about Ukraine?” Thorpe said.

Los Angeles Times photographer Marcus Yam is on the ground in London to bring a visual perspective as Britain says goodbye to the queen.

Such concerns were set aside inside the abbey, where Justin Welby, the archbishop of Canterbury, gave a homily that ended with the words “We will meet again” — an echo of a message delivered by the queen during the COVID-19 pandemic to comfort those who had lost loved ones. Her use of the phrase was itself drawn from the song “We’ll Meet Again” by Vera Lynn, an iconic piece in Britain from World War II.

Soon after, a military bugler played the Last Post, similar to Taps in the U.S., signaling the service’s conclusion and the start of two minutes of silence in remembrance of the queen. It was a quiet that hung heavy outside the abbey’s walls: Takeoffs and landings at London’s Heathrow Airport, one of the world’s busiest, were suspended for half an hour so as not to disrupt the silence. In Hyde Park, many stood ramrod straight, with heads bowed in a moment of uniform solemnity remarkable for a crowd that size.

Funeral attendees then sang the national anthem, some of them saying the words “God save the king” for the first time. A final lament from the queen’s bagpiper brought the service to a close.

Then, as the sun pierced through the heavy cloud cover that had blanketed London in the morning, Royal Navy sailors took the casket once more to Wellington Arch, to the sounds of a funeral march backed by Big Ben’s tolling and the loud report of artillery guns. The coffin was loaded onto a hearse, which drove to Windsor Castle.

After the funeral, the tables outside the City of Quebec pub just across from Hyde Park filled up quickly.

“To the queen,” a group of three friends said as they clinked glasses of Guinness beer and watched ongoing BBC coverage of the procession on a cellphone.

Royal mourning will temporarily turn attention away from Britain’s many pressing problems and how a new prime minister will tackle them. Then what?

Reflecting on “the end of an era,” Zoe Dearsley marveled at the queen’s seven decades of service.

“She served for all that time with such grace. To be 96, two days from death and still doing her duty, meeting with Boris Johnson and Liz Truss, probably the last thing she wanted to do, it’s just remarkable.”

Her boyfriend, Dan Ellis, said that, as a native South African, he’s always been somewhat less enamored of the British monarchy but still recognized the queen’s dedication and staying power.

“I’m somewhat skeptical of monarchy generally, but she had such character,” he said. “She was the best of leadership.”

Bulos, Stokols and Chu are staff writers. Boyle is a special correspondent. Times foreign correspondent and photographer Marcus Yam contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.