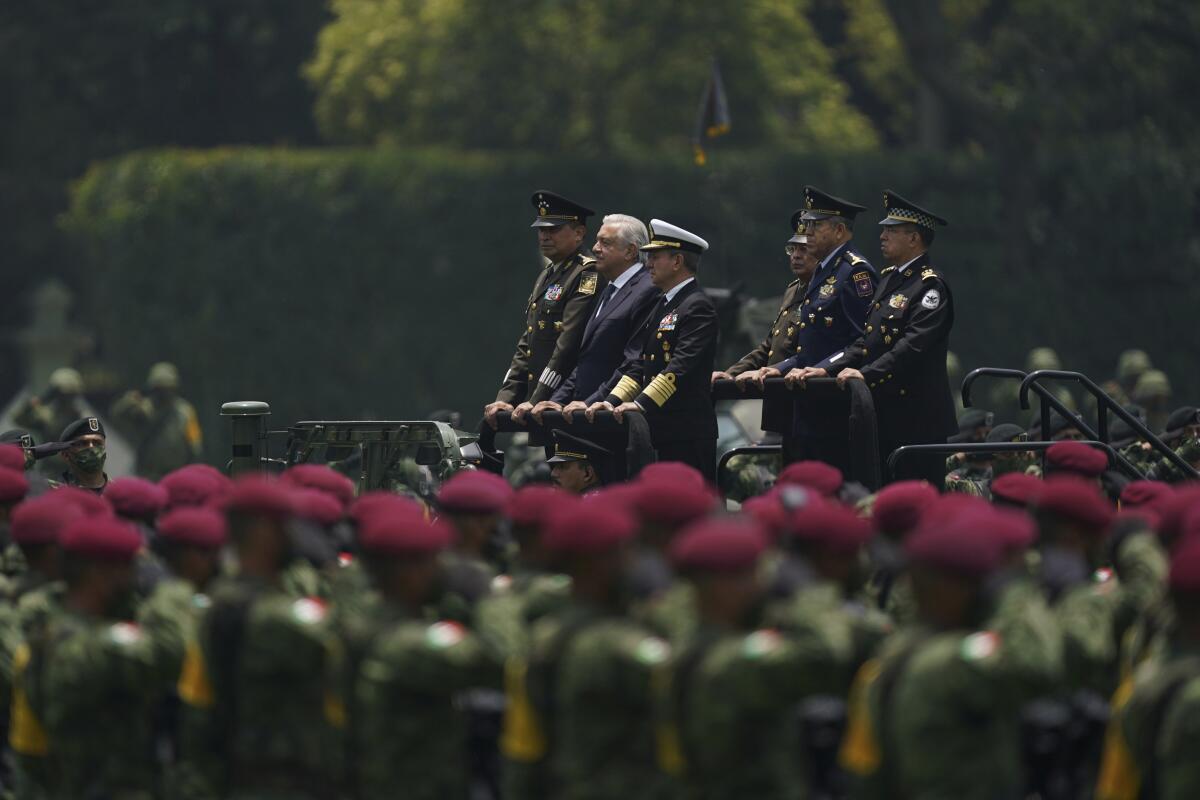

Mexico’s president vowed to end the drug war. Instead he’s doubled the number of troops in the streets

MEXICO CITY — After cartels unleashed a wave of violence across Mexico last week, killing civilians, blocking roads with burning vehicles and setting dozens of stores on fire, the government here responded as it often does to an outbreak of lawlessness: It sent in the troops.

The thousands of soldiers and National Guard members who arrived in the cities of Tijuana, Juarez and Guadalajara in recent days appeared ready for combat with helmets, camouflage and assault rifles strapped across their ballistic vests.

American tourists and remote workers are gentrifying some of Mexico City’s most treasured neighborhoods. Backlash is growing.

It was a reminder of not only the ongoing security crisis gripping this nation but also President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s failed promise to pull soldiers off the streets.

As a candidate, López Obrador vowed a radical break with the militarized security strategy of his predecessors, which he blamed for turning Mexico “into a cemetery.”

He floated the idea of drug legalization and amnesty for criminals and promised to lift up poor communities with “hugs, not bullets.” Insisting that soldiers “don’t solve anything,” he repeatedly vowed to “return the army to the barracks.”

Yet since taking office nearly four years ago, López Obrador has embraced the armed forces with unprecedented fervor, expanding many of the same policies that he once attacked.

More than 200,000 federal troops are deployed across Mexico — more than twice as many as at any point since the country launched its war on drug traffickers 16 years ago.

That includes members of an expanded military and navy as well as more than 92,000 members of the National Guard, a new force created by López Obrador that is trained by the army and is mostly made up of former soldiers.

The president initially pledged to keep the National Guard under civilian rule and to remove the army from the streets entirely by the end of his term in 2024.

Now he says he plans to place the National Guard under control of the armed forces — and mandate that the armed forces be allowed to continue their policing role indefinitely.

Derided by lawmakers as unconstitutional, his proposal has revived a long-running debate about whether the military, a force designed to battle foreign armies, should be used to fight domestic crime.

The consensus among security experts, human rights advocates and many public officials is that federal troops are simply not cut out for a job that requires an intimate knowledge of local communities and training in investigations and crime prevention.

To make their case they point to the soaring death toll in the years since 2006, when then-President Felipe Calderón first called on the military to help combat drug cartels — an arrangement he said would be temporary.

That year, 10,452 people were killed in Mexico.

Homicides today hover at more than 35,000 a year. An additional 30,000 people have gone missing during López Obrador’s term alone.

Entire industries here are now dominated by organized crime, and a U.S. military official recently estimated that a third of Mexico is “ungoverned territory,” where criminal groups operate with impunity.

“We have decades of accumulated evidence to show that militarizing public security doesn’t solve Mexico’s violence problem,” said Stephanie Brewer, an expert on security and human rights at the think tank Washington Office on Latin America. “It’s not realistic to expect that by doing the same thing you’re going to produce different results.”

Brewer and others have long insisted that peace in Mexico depends on reforming the nation’s corrupt police forces and reducing impunity by teaching prosecutors how to properly investigate crimes. The U.S. government agrees, and it has spent hundreds of millions of dollars on training programs for the armed forces and police.

But López Obrador has slashed police budgets. He also disbanded the federal police force, which had been dogged by allegations that authorities were colluding with the criminals they were supposed to be fighting.

Instead of trying to reform law enforcement, López Obrador put his faith in the army and the navy — which are consistently ranked as two of the nation’s most trusted institutions.

Traditionally, the military played a limited role in public security and civilian affairs here, setting Mexico apart from other parts of Latin America that suffered coups and military governments.

Under an arrangement set eight decades ago by the then-dominant Institutional Revolutionary Party, the military was left to its own devices so long as it didn’t interfere in governance. Without wars to fight, the troops attracted little public attention.

López Obrador has not only kept the armed forces in charge of policing but also expanded their duties well beyond security, giving them control of civilian tasks.

Troops now lead the fight against illegal immigration, the COVID-19 pandemic and the theft of fuel from gas lines. They run the country’s biggest infrastructure projects — including construction of an airport and a major train line — and control the nation’s ports and border crossings.

It’s not just drugs. Mexico’s cartels are fighting over avocados.

The newfound alliance between the president and the armed forces has fueled speculation and fear about his motives. Some say López Obrador needs the military because he has alienated many of the nation’s traditional power brokers — including its business elite and the opposition parties that maintain strong links to public-sector unions.

Others worry he is consolidating power before a potential attempt to stay in office after his term ends.

“Why does he insist on giving more and more responsibilities to the army?” security expert Ernesto López Portillo said. “What does the president want after 2024?”

López Obrador, who denies that he intends to violate the constitution by serving more than one six-year-term, says he has turned to the army because it is one of the most efficient and least corrupt branches of government in Mexico.

Human rights officials worry about the potential for abuse.

Misconduct in the armed forces — including killings, forced disappearances and torture — is typically investigated by the military institutions themselves instead of by civilian prosecutors and rarely results in punishment.

There are some indications that suggest the armed forces have taken a new, less aggressive tack under López Obrador. Whereas the military once confronted organized crime head on, sometimes killing bystanders in shootouts, today’s troops seem more focused on street patrols than cartel battles.

In Michoacan state, for example, locals have complained that the army simply acts as a buffer between criminal groups instead of directly challenging them.

Data show troops have been engaged in fewer shootouts than under the two previous presidents and have seized fewer numbers of guns — perhaps a sign that the president’s “hugs, not bullets” rhetoric has trickled down to the troops on the ground.

Still, hundreds of people have filed complaints about the armed forces with the National Human Rights Commission since López Obrador took office. There have been high-profile cases in which troops appeared to act extrajudiciously, including one in which a National Guard member killed a 19-year-old university student.

Even with homicides near all-time highs and regular bursts of violence such as the one seen last week, López Obrador and the armed forces maintain high approval ratings.

It may seem like a paradox, but it’s not, said Carlos Bravo Regidor, a professor at the CIDE public research institute in Mexico City.

“In times of uncertainty, in times of fear, institutions built around the image of discipline become the place where people run to,” he said. “People gravitate toward solutions of order more than solutions of justice.”

He said he felt dispirited.

“We’ve been here for 15 years, and it’s disheartening to feel that we’ve dug ourselves into such a profound hole, and we’re still saying, you know, our only chance is to keep digging,” he said.

Special correspondent Cecilia Sánchez in The Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.