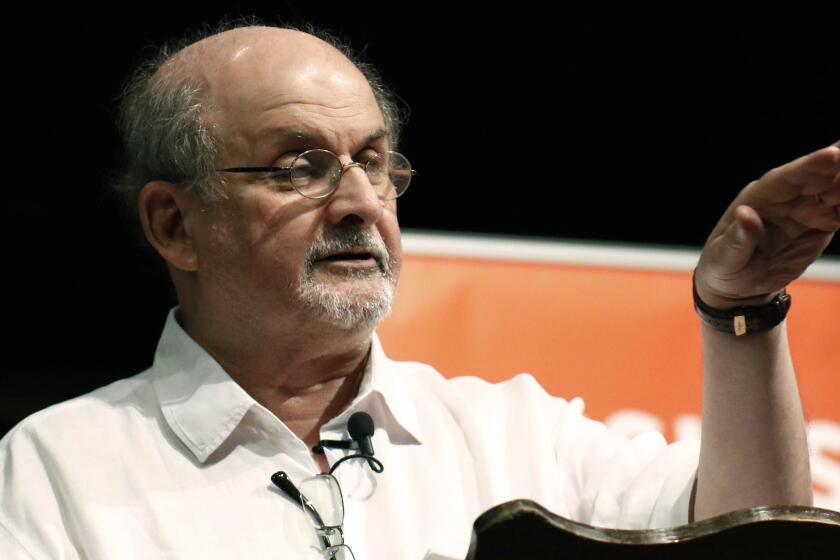

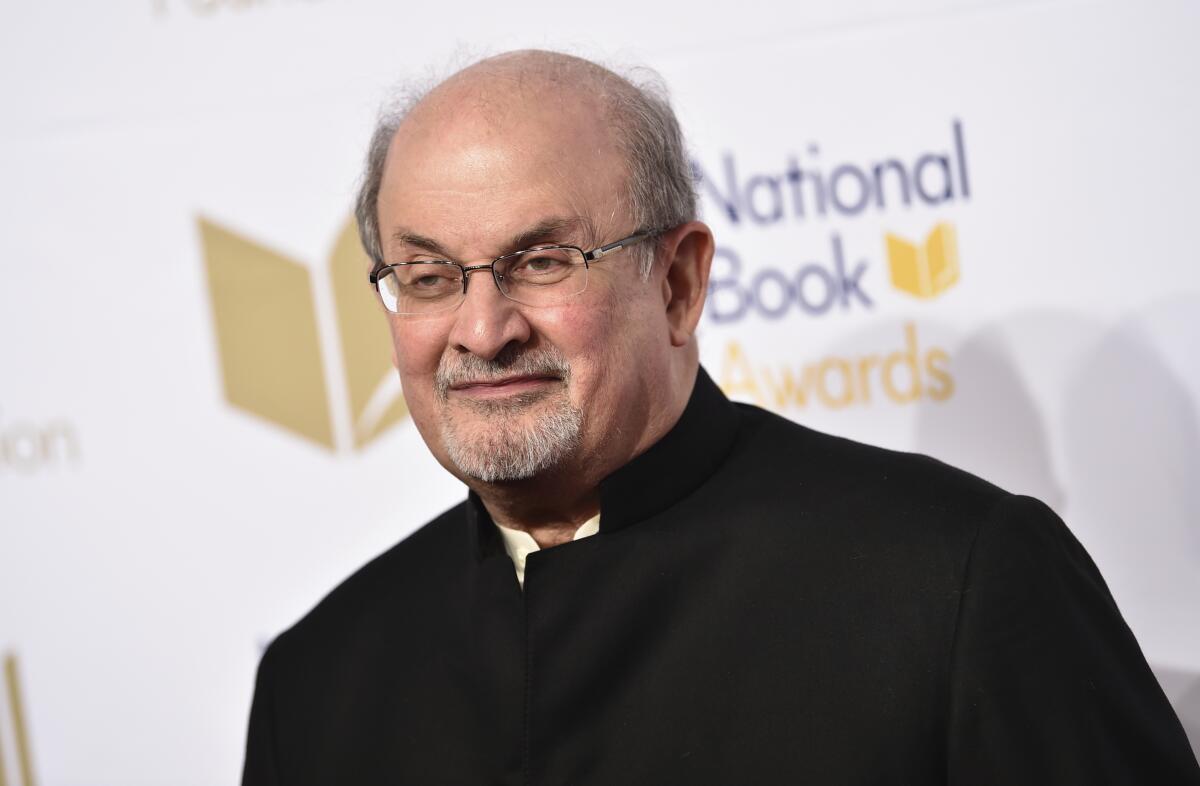

Attack on Salman Rushdie praised by some Iranians. Others worry it could hurt their country

TEHRAN — Iranians reacted with praise and worry Saturday over the attack on novelist Salman Rushdie, the target of a decades-old fatwa by the late Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini calling for his death.

It remains unclear why Rushdie’s attacker, identified by police as Hadi Matar of Fairview, N.J., stabbed the author as he prepared to speak at an event Friday in western New York. Iran’s theocratic government and its state-run media have attributed no motive to the assault.

But in Tehran, some willing to speak to the Associated Press offered praise for an attack targeting a writer they believe tarnished the Islamic faith with his 1988 book “The Satanic Verses.” In the streets of Iran’s capital, images of Khomeini still peer down at passersby.

“I don’t know Salman Rushdie, but I am happy to hear that he was attacked since he insulted Islam,” said Reza Amiri, a 27-year-old deliveryman. “This is the fate for anybody who insults sanctities.”

Others, however, worried aloud that Iran could become even more cut off from the world as tensions remain high over its tattered nuclear deal.

“I feel those who did it are trying to isolate Iran,” said Mahshid Barati, a 39-year-old geography teacher. “This will negatively affect relations with many — even Russia and China.”

A fatwa was issued against Salman Rushdie in 1989 over his book ‘The Satanic Verses.’ But what is a fatwa and how has it affected his life and career?

Khomeini, in poor health in the last year of his life after the grinding, stalemate 1980s Iran-Iraq war decimated the country’s economy, issued the fatwa on Rushdie in 1989. The Islamic edict came amid a violent uproar in the Muslim world over the novel, which some viewed as blasphemously making suggestions about the prophet Muhammad’s life.

“I would like to inform all the intrepid Muslims in the world that the author of the book entitled ‘Satanic Verses’ ... as well as those publishers who were aware of its contents, are hereby sentenced to death,” Khomeini said in February 1989, according to Tehran Radio.

He added: “Whoever is killed doing this will be regarded as a martyr and will go directly to heaven.”

Early Saturday, Iranian state media made a point to remember one man who died trying to carry out the fatwa. Lebanese national Mustafa Mahmoud Mazeh died when a book bomb prematurely exploded in a London hotel on Aug. 3, 1989, a little more than 33 years ago.

Matar, the man who authorities say attacked Rushdie on Friday, was born in the United States to Lebanese parents who emigrated from the southern village of Yaroun, said the town’s mayor, Ali Tehfe.

Yaroun is only miles from Israel. In the past, the Israeli military has fired on what it described as positions of the Iran-backed Shiite militia Hezbollah around that area.

At newsstands Saturday, front-page headlines offered their own takes on the attack. The hard-line Vatan-e Emrouz’s main story covered what it described as: “A knife in the neck of Salman Rushdie.” The reformist newspaper Etemad’s headline asked: “Salman Rushdie near death?”

The conservative newspaper Khorasan bore a large image of Rushdie on a stretcher, its headline blaring: “Satan on the path to hell.”

But the 15th Khordad Foundation — which put a bounty of more than $3 million on Rushdie — remained quiet. Staffers there declined to immediately comment.

The foundation, whose name refers to the 1963 protests against Iran’s former shah by Khomeini’s supporters, typically focuses on providing aid to disabled people and others affected by war. But it, like other foundations known as “bonyads” in Iran funded in part by confiscated assets from the shah’s time, often serve the political interests of the country’s hard-liners.

Reformists in Iran, those who want to slowly liberalize the country’s Shiite theocracy from inside and have better relations with the West, have sought to distance the country’s government from the edict. Notably, reformist President Mohammad Khatami’s foreign minister in 1998 said that the “government disassociates itself from any reward which has been offered in this regard and does not support it.”

Rushdie slowly began to reemerge into public life around that time. But some in Iran have never forgotten the fatwa against him.

On Saturday, Mohammad Mahdi Movaghar, a 34-year-old Tehran resident, described having a “good feeling” after seeing Rushdie attacked.

“This is pleasing and shows those who insult the sacred things of we Muslims, in addition to punishment in the hereafter, will get punished in this world too at the hands of people,” he said.

Others, however, worried the attack — regardless of why it was carried out — could hurt Iran as it tries to negotiate over its nuclear deal with world powers.

Since then-President Trump unilaterally withdrew America from the accord in 2018, Tehran has seen its rial currency plummet and its economy crater. Meanwhile, Tehran enriches uranium now closer than ever to weapons-grade levels amid a series of attacks across the Mideast.

“It will make Iran more isolated,” said former Iranian diplomat Mashallah Sefatzadeh.

Though fatwas can be revised or revoked, Iran’s current supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who took over after Khomeini, has never done so.

“The decision made about Salman Rushdie is still valid,” Khamenei said in 1989. “As I have already said, this is a bullet for which there is a target. It has been shot. It will one day sooner or later hit the target.”

As recently as February 2017, Khamenei tersely answered this question posed to him: “Is the fatwa on the apostasy of the cursed liar Salman Rushdie still in effect? What is a Muslim’s duty in this regard?”

Khamenei responded: “The decree is as Imam Khomeini issued.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.