This week’s floods have ‘dramatically changed’ Yellowstone’s landscape, perhaps forever

RED LODGE, Mont. — Floodwaters that rushed through Yellowstone National Park and surrounding communities earlier this week moved through Montana’s largest city on Wednesday, flooding farms and ranches and forcing the shutdown of its water treatment plant.

The water in the Yellowstone River hit its highest level in nearly a century as it traveled east to Billings, home to nearly 110,000 people. It hit 16 feet, a foot higher than the water plant needs to work effectively.

The historic floodwaters raged through the nation’s oldest national park earlier this week and may have forever altered the human footprint on Yellowstone’s terrain and the communities that have grown around it.

The floodwaters tore out bridges and poured into nearby homes. They pushed a popular fishing river off course — possibly permanently — and may force roadways nearly torn away by torrents of water to be rebuilt in new places.

“The landscape literally and figuratively has changed dramatically in the last 36 hours,” said Bill Berg, a commissioner in nearby Park County, Mont. “A little bit ironic that this spectacular landscape was created by violent geologic and hydrologic events, and it’s just not very handy when it happens while we’re all here settled on it.”

The unprecedented flooding drove more than 10,000 visitors out of the park and damaged hundreds of homes in nearby communities, though remarkably no one was reported hurt or killed. The only visitors left in the massive park straddling three states were a dozen campers still making their way out of the backcountry.

The park could remain closed as long as a week, and northern entrances may not reopen this summer, Supt. Cam Sholly said.

“I’ve heard this is a 1,000-year event, whatever that means these days. They seem to be happening more and more frequently,” he said.

Sholly noted that some weather forecasts include the possibility of more flooding this weekend.

Days of rain and rapid snowmelt wrought havoc across parts of southern Montana and northern Wyoming, where it washed away cabins, swamped small towns and knocked out power. It hit the park as a summer tourist season that draws millions of visitors was ramping up during the park’s 150th anniversary year.

Businesses in hard-hit Gardiner, Mont., had just started recovering from the tourism contraction brought by the COVID-19 pandemic and were hoping for a good year, Berg said.

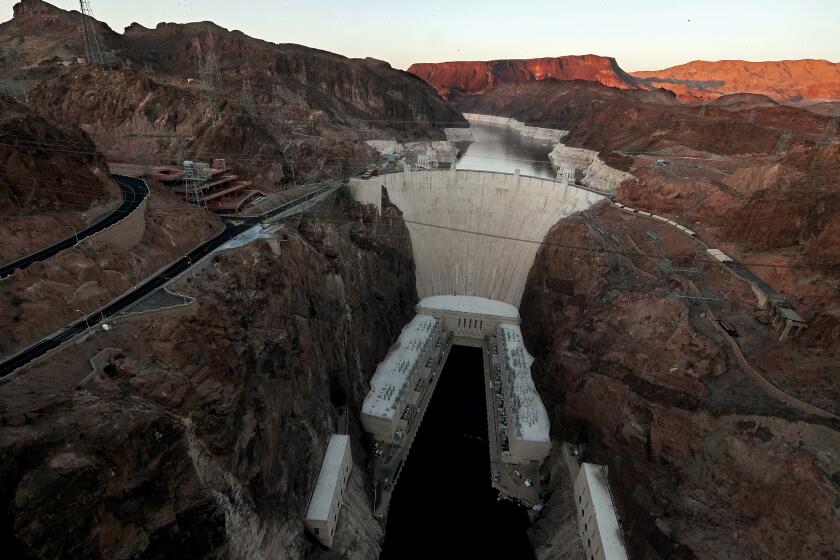

As the Colorado River water shortage worsens, major cutbacks are needed to reduce most perilous risks, a federal official tells senators.

“It’s a Yellowstone town, and it lives and dies by tourism, and this is going to be a pretty big hit,” he said. “They’re looking to try to figure out how to hold things together.”

Some of the worst damage occurred in the northern part of the park and Yellowstone’s gateway communities in southern Montana. National Park Service photos of northern Yellowstone showed a mudslide, washed-out bridges and roads undercut by churning floodwaters of the Gardner and Lamar rivers.

In Red Lodge, a town of 2,100 that’s a popular jumping-off point for a scenic route into the Yellowstone high country, a creek jumped its banks and swamped the main thoroughfare, leaving trout swimming in the street a day later under sunny skies.

Residents described a harrowing scene where the water went from a trickle to a torrent in just a few hours.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The water toppled telephone poles, knocked over fences and carved deep fissures in the ground through a neighborhood of hundreds of houses. Electricity was restored by Tuesday, but there was still no running water in the neighborhood.

Heidi Hoffman left early Monday to buy a sump pump in Billings, but by the time she returned, her basement was full of water.

“We lost all our belongings in the basement,” Hoffman said as the pump removed a steady stream of water into her muddy backyard. “Yearbooks, pictures, clothes, furniture. We’re going to be cleaning up for a long time.”

At least 200 homes were flooded in Red Lodge and the town of Fromberg.

Forest thinning is now being conducted at Yosemite National Park. Environmentalists want it to stop, saying the work was never fully vetted.

The flooding came as the Midwest and East Coast sizzle from a heat wave and other parts of the West burn from an early wildfire season amid a persistent drought that has increased the frequency and intensity of fires. Smoke from a fire in the mountains of Flagstaff, Ariz., could be seen in Colorado.

While the flooding hasn’t been directly attributed to climate change, Rick Thoman, a climate specialist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, said a warming environment makes extreme weather events more likely than they would have been “without the warming that human activity has caused.”

“Will Yellowstone have a repeat of this in five or even 50 years? Maybe not, but somewhere [it] will have something equivalent or even more extreme,” he said.

Climate change is making the world more prone to floods like those in China and Europe and to heat waves and fires like those in the U.S. and Russia.

Heavy rain on top of melting mountain snow pushed the Yellowstone, Stillwater and Clarks Fork rivers to record levels Monday and triggered rock and mudslides, according to the National Weather Service. The Yellowstone River at Corwin Springs topped a record set in 1918.

Yellowstone’s northern roads may remain impassable for a substantial length of time. The flooding affected the rest of the park, too, with park officials warning of yet higher flooding and potential problems with water supplies and wastewater systems at developed areas.

The rains hit just as area hotels filled up in recent weeks with summer tourists. More than 4 million visitors were tallied by the park last year. The wave of tourists doesn’t abate until fall, and June is typically one of Yellowstone’s busiest months.

At a cabin in Gardiner, Parker Manning of Terre Haute, Ind., got an up-close view of the roiling Yellowstone River floodwaters just outside his door.

A federal firefighter’s viral resignation letter is highlighting the job’s low pay and harsh working conditions in the age of climate change.

In early evening, he shot video as the waters ate away at the opposite bank, where a large brown house that had been home to park employees was precariously perched.

In a large cracking sound heard over the river’s roar, the house tipped into the waters and was pulled into the current.

The towns of Cooke City and Silvergate, just east of the park, were also isolated by floodwaters, which also made drinking water unsafe. People left a hospital and low-lying areas in Livingston.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.