U.S. identifies Native American boarding schools, burial sites

FLAGSTAFF, Ariz. — A first-of-its-kind federal study of Native American boarding schools that for over a century sought to assimilate Indigenous children into white society has identified more than 400 such schools that were supported by the U.S. government and more than 50 associated burial sites, a figure that could grow exponentially as research continues.

The report released Wednesday by the Interior Department expands the number of schools that were known to have operated for 150 years, starting in the early 19th century and coinciding with the removal of many tribes from their ancestral lands.

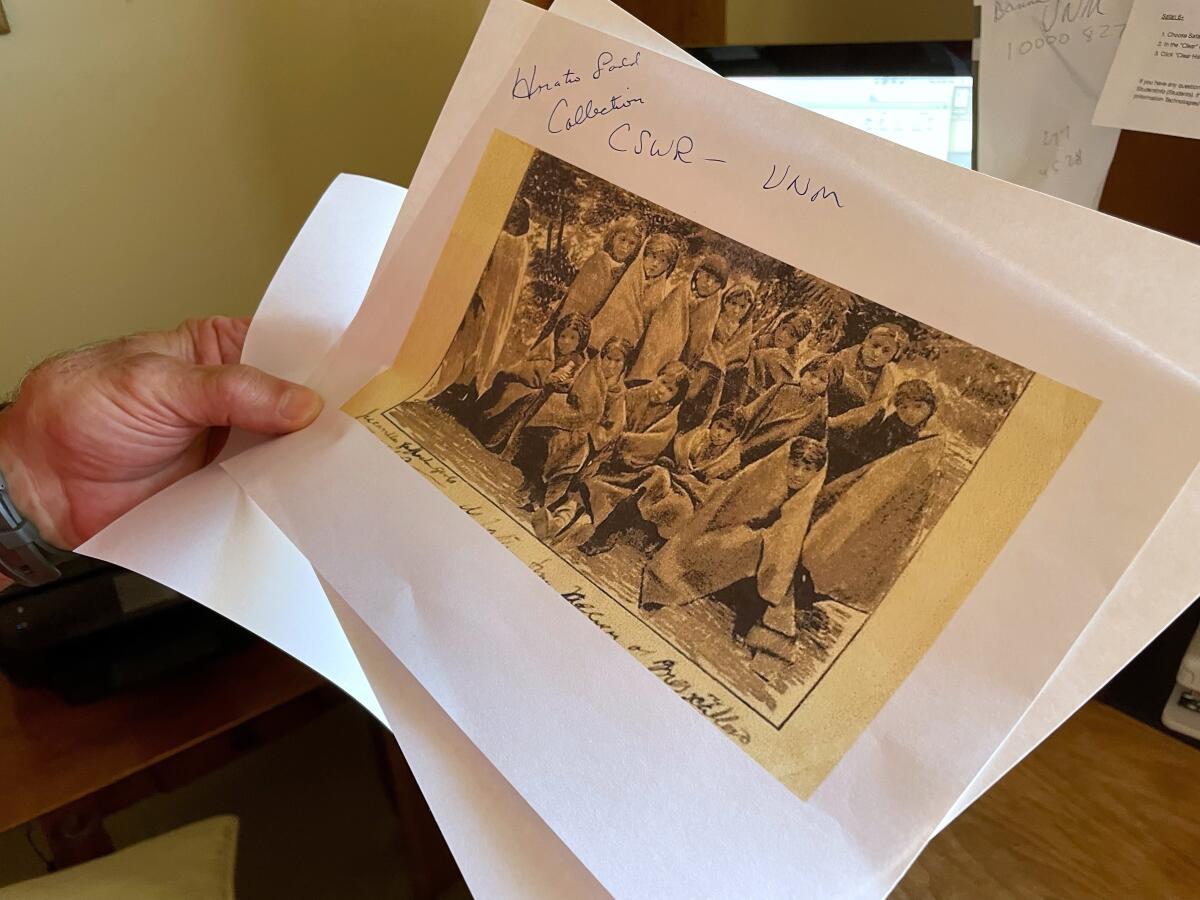

The dark history of the boarding schools — where children were taken from their families, prohibited from speaking their Native American languages and often abused — has been felt deeply across Indian Country and through generations of families.

Many children never returned home, and the department’s work focused on burial sites and trying to identify the children and their tribal affiliations is far from complete.

“The consequences of federal Indian boarding school policies — including the intergenerational trauma caused by the family separation and cultural eradication inflicted upon generations of children as young as 4 years old — are heartbreaking and undeniable,” Interior Secretary Deb Haaland said in a statement.

Haaland, who is a member of the Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico, announced an initiative in June to investigate the troubled legacy of boarding schools and uncover the truth about the federal government’s role in them.

The 408 schools her agency identified operated in 37 states or territories, many of them in Oklahoma, Arizona and New Mexico. Twelve schools operated in California, the report said.

The Interior Department acknowledged the number of schools identified could change as more data are gathered. The COVID-19 pandemic and budget restrictions hindered some of the research over the last year, said Bryan Newland, the Interior Department’s assistant secretary for Indian affairs.

The U.S. government directly ran some of the boarding schools. Catholic, Protestant and other churches operated others with federal funding, backed by U.S. laws and policies to “civilize” Native Americans.

The Interior Department report was prompted by the discovery of hundreds of unmarked graves at former residential school sites in Canada that brought back painful memories for Indigenous communities.

Haaland also announced Wednesday a yearlong tour for Interior Department officials that will allow former boarding school students from Native American tribes, Alaska Native villages and Native Hawaiian communities to share their stories as part of a permanent oral history collection.

News Alerts

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“It is my priority to not only give voice to the survivors and descendants of federal Indian boarding school policies, but also to address the lasting legacies of these policies so Indigenous peoples can continue to grow and heal,” she said.

Boarding school conditions varied across the U.S. and Canada. Though some former students have reported positive experiences, children at the schools often were subjected to military-style discipline and had their long hair cut.

Early curricula focused heavily on outdated vocational skills, including homemaking for girls.

The Interior Department found at least 53 burial sites at or near the U.S. boarding schools, both marked and unmarked, and said the number of children who died at federal boarding schools could be in the thousands or tens of thousands.

“Many of those children were buried in unmarked or poorly maintained burial sites far from their Indian Tribes, Alaska Native Villages, the Native Hawaiian Community, and families, often hundreds, or even thousands, of miles away,” the report said.

Tribal leaders have pressed the agency to ensure that the children’s remains are properly cared for and delivered back to their tribes, if desired. The locations of the sites will not be identified to prevent them from being disturbed, Newland said.

Accounting for the whereabouts of children who died has been difficult because records weren’t always kept. Ground-penetrating radar has been used in some places to search for remains.

A second volume of the investigative report will cover the burial sites as well as the federal government’s financial investment in the schools and the impact of the boarding schools on

Indigenous communities, the Interior Department said.

The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, which created an early inventory of the schools, has said the Interior Department’s work will be an important step for the U.S. in reckoning with its role in the schools but noted that the agency’s authority is limited.

This week, a U.S. House subcommittee will hear testimony on a bill to create a truth and healing commission modeled after one in Canada. Several church groups are backing the legislation.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.