Can China preserve both its economy and its zero-tolerance COVID-19 policy?

TAIPEI, Taiwan — China’s zero-COVID strategy is starting to derail another major item on the government’s agenda: economic stability.

In the last month, sweeping lockdowns across the country have crimped manufacturing. Stay-at-home orders have stunted consumer spending. The closures are also compounding supply chain issues that have boosted inflation and weighed on global growth.

“No part of China’s economy is untouched by the tightening of zero-COVID policies,” Craig Botham, chief China economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, wrote in a research report to clients this week.

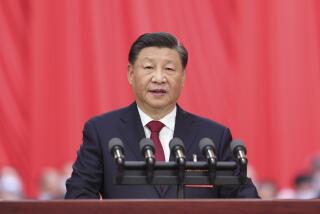

The costs of prioritizing the pandemic over all else are creating a dilemma for President Xi Jinping as he prepares to assume a third term later this year.

China’s initial success in stopping the spread of COVID-19 while the West floundered became validation for some of the strictest coronavirus control policies in the world. But it’s unclear how long the country’s leaders can maintain those policies without sacrificing the economic growth that has long been the bedrock of their rule.

The 5.5% gross domestic product growth target that China set in March is looking more elusive the longer that lockdowns go on.

Compared with the early days of the pandemic, China is now facing a more contagious variant as well as dwindling public patience for harsh restrictions and growing criticism from the normally muted business community.

“The system’s focus on zero-COVID leads to many decision makers being in a kind of self-destruction mode,” Joerg Wuttke, president of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China, recently told the financial publication the Market NZZ. “They don’t care about the economy in the short term.”

He said some foreign companies are so discouraged that they are considering reducing operations in the country: “China is losing its credibility as the best sourcing location in the world.”

The most consequential shutdown has been in Shanghai, the country’s biggest city with a population of 25 million.

When the virus began to spread in March, officials there were slow to shutter factories and businesses given the city’s economic importance. But by April, the manufacturing and financial hub was under full lockdown, logging tens of thousands of new cases a day.

Other cities, fearing a similar fate, have been quicker to impose restrictions after local outbreaks. By mid-April, 87 out of China’s 100 biggest cities by GDP had imposed some form of lockdown, according to Beijing-based Gavekal Dragonomics.

Economists are scrambling to predict the impact.

One study from the Chinese University of Hong Kong and Tsinghua University estimated that a one-month countrywide lockdown would reduce quarterly GDP by 22.3%, while a lockdown limited to China’s four largest cities — Beijing, Guangzhou, Shanghai and Shenzhen — would reduce the country’s GDP by 8.6%.

“The problem is that this thing can pop up at any time,” said Gene Ma, head of China research at the Institute of International Finance in Washington. “That’s what makes the situation so precarious.”

In 2020, when China locked down the city of Wuhan and limited movement nationwide, GDP dropped 6.8% in the first quarter of the year, but the economy swiftly recovered. Last year’s growth was 8.1%.

GDP rose 4.8% in the first quarter of this year, but with manufacturing and service sector activity contracting in April to the lowest level in more than two years, economists have gloomier expectations for the next few months.

In April, the International Monetary Fund revised its annual growth forecast for China to 4.4%, down from 4.8%.

The effects of a slowdown extend far beyond China.

The global economy is already under pressure from high inflation and the war in Ukraine. The IMF, which recently lowered its worldwide growth forecast to 3.6% from 4.4%, warned in a report that more disruptions in China could further impede growth in countries that rely most on it for trade.

In South Korea, a major trading partner, exports have dropped to a two-year low. “This is ominous for exporters elsewhere,” Botham wrote. “The wellspring of the weakness is China, with an economy paralyzed by zero-COVID policies.”

Even if China is able to get COVID under control, it still has to confront a struggling property market, declining global demand for consumer goods and high debt fueled by infrastructure investment, according to Neil Shearing, chief economist at the Capital Economics group in London.

China’s slowdown is also hitting the labor market, with layoffs, worker disillusionment and rising unemployment just as a record number of college graduates are entering the workforce.

“While the recent focus has understandably been on the immediate fallout from the latest COVID outbreak, the challenges facing economic policymakers in Beijing extend well beyond the next few quarters,” Shearing wrote in a report this week.

In a video recording reported by the Financial Times, Weijian Shan, chairman of one of Asia’s largest private equity firms, PAG, said that the fund was taking a cautious approach to investing in China as its lockdown policies had pushed market sentiment and economic prospects to a 30-year low.

China is taking some steps to ease the pain.

In a Politburo meeting last week, Communist Party leaders said they would implement tax cuts, infrastructure development and assistance for businesses and individuals to mitigate the economic uncertainty.

Chinese officials have also attempted to keep some factories running during the lockdown with closed-loop systems, where workers live and travel within a smaller, infection-free community.

Hundreds of companies — perhaps most notably, Tesla — have been allowed to resume production in Shanghai. However, they could still struggle to get parts given closures elsewhere, said Eric Zheng, president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai.

“These days when talking about supply chains, you’re talking about different part suppliers, so you need to open up all those sectors in order to support a company like Tesla,” he said. “I wouldn’t be surprised if after COVID companies are taking another look at their global supply chain strategy by including all these risk factors.”

Nathan Strang, director of ocean lane management at the freight-forwarding company Flexport, said that although Shanghai’s port is still open, bookings have fallen about 40% since the coronavirus outbreak. His clients have been grappling with manufacturing delays and shipping stoppages — and deep uncertainty about the future.

“There’s concern growing as the lockdown continues,” Strang said. “They rely on their manufacturers and suppliers to give them a sense of what’s going on. Trying to get that information has been extremely difficult and frustrating.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.