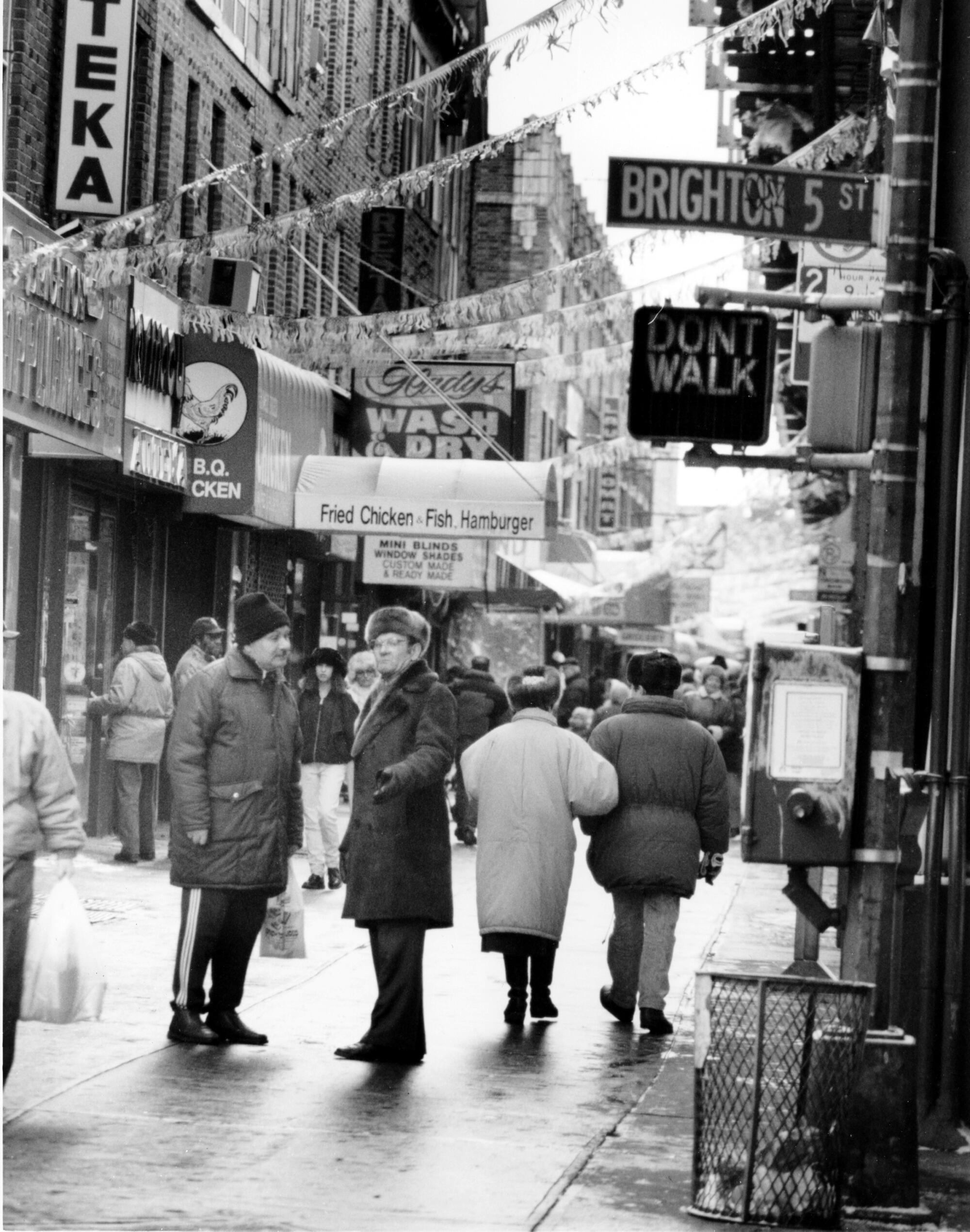

BROOKLYN, N.Y. — Nonna Kontorov was not yet 2 years old when her family fled the Soviet Union, part of the first wave of Jewish refugees allowed to leave. In 1974 they arrived in Brighton Beach, a former seaside resort at the end of the subway line in Brooklyn. Tens of thousands would follow.

“We were like the first five families,” Kontorov recalled on a recent afternoon, pointing at the block off Brighton Beach Avenue where she grew up alongside other Soviet emigres. “Our home was the welcoming station. My father would go to the airport, pick up the families and bring them home. I remember making the drive with him many times.”

With 10,000 Ukrainians fleeing war arriving in Berlin each day, a range of emotions and fear grips the new refugees.

Today, Brooklyn is home to 123,000 Russian speakers, more than any U.S. county. Many of them are concentrated in Brighton Beach. Ethnic Russians, Ukrainians and Jews — along with growing numbers of Georgians, Uzbeks, Tajiks and other denizens of former Soviet republics — live and work side by side here, the distinctions among them blurred by shared language and immigrant status.

Since Russia invaded Ukraine in late February, sending civilians underground and out of the country and spurring worldwide sanctions, Brighton Beach has become a place for Ukrainians to affirm their identity with pride, flaunting the blue and yellow of their country’s flag and filling the air with Ukrainian speech. It has become a hub for non-Ukrainians, too, to show solidarity.

And it is now the site of quiet — and not-so-quiet — rifts over politics.

“This really hits home for us,” said Michael Levitis, who hosts a Russian radio program and a Facebook group for Russian speakers in America, many of whom are in Brighton Beach. “We all have friends and relatives in Ukraine and Russia … Just 30 years ago we were all one country.”

The United States is home to 1.2 million immigrants from the former Soviet Union. The majority of those born in Ukraine came before the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991 or in its aftermath, according to data analyzed by the Migration Policy Institute, an independent research group in Washington.

In Brighton Beach, these immigrants shop together at the Brighton Bazaar and Tashkent supermarkets amid the din of trains overhead. They soak next to one another in hot tubs at the banyas of neighboring Coney Island and Gravesend. And they play heated card games on the century-old oceanfront boardwalk.

Russian forces kept up attacks on suburbs of Kyiv and the city of Mariupol and said they used hypersonic missiles to destroy an ammunition depot.

“It’s like the epicenter of the world for all Russian-speaking people,” Kontorov said.

She can’t walk far without running into a familiar face, whom she inevitably greets in Russian.

“I don’t know where half of them are from, my Russian-speaking friends,” said Kontorov, who was born in Chernivtsi, Ukraine. “It was never a thing to ask. Now it’s become a thing.”

Brighton Beach was first developed in the late 1800s as a beach resort. In the early 20th century it became home to upwardly mobile Jews from Eastern Europe and other parts of New York City, according to the Brooklyn Jewish Historical Initiative. Another influx of Jews came after World War II.

But by 1970 the area was in decline, battered by crime and the flight of well-heeled residents to other neighborhoods and the suburbs.

At that time in the Soviet Union, a change in migration policy allowed Jews and others to begin leaving in greater numbers. Many came to Brighton Beach. Soon people were calling the area “Little Odessa” for its large Ukrainian population.

The community grew so large that in 1981 New York magazine ran a five-page spread titled “A Little Russia Grows in Brooklyn.” The opening image featured Kontorov’s parents dancing at the National restaurant and nightclub.

“It was the place to be,” Kontorov said of the restaurant, which offered 10-course banquets, free-flowing vodka, and cabaret shows with skimpily clad dancers.

President Biden and China’s President Xi Jinping spoke by phone as the White House sought to convince Beijing not to support Russia’s war in Ukraine.

The National closed three years ago. But the stretch of Brighton Beach Avenue where it stood is named Sofia Vinokurov and Mark Rakhman Place, after the siblings from Ukraine who owned it.

Today Bobby Rakhman, Mark’s son, co-owns a grocery a few blocks down.

The Taste of Russia’s hot prepared foods — including golubtsi (cabbage rolls), fried fish, and meatballs in sour cream sauce — are its biggest draw. Pickled apples, cucumbers, cabbage and carrots fill deep buckets in the back. Zefir, or homemade marshmallows, entice customers up front.

“If you’re a non-Russian-speaker, they’ll ignore you,” Kontorov joked, guiding a reporter past a line that stretched through the store on a Friday afternoon.

Business has been steady since the start of the war, Rakhman said. Almost all of his clientele is Russian-speaking. But he and his partner recently changed the name to International Food. “People feel very offended by the term ‘Russia,’ and we made a corporate decision to take it off,” Rakhman said.

Most of his employees are Ukrainian. “We wanted to show solidarity,” he said.

Up and down the avenue there were other signs of support for Ukraine. Windows displayed QR codes to donate. Mannequins in a clothing store were dressed in blue and yellow. Ukrainian flags hung on the street corner.

The U.S. and Europe, and the West’s allies, want Russia to pay a harsh economic price for invading Ukraine. But some elsewhere say: Not so fast.

Jeanne Batalova, senior policy analyst at the Migration Policy Institute, was born in Ukraine, grew up in Moldova and has Jewish ancestry. She said the war is spurring Ukrainians and others from all over the former Soviet Union to take a closer look at their identity.

“The identity is kind of dormant until something happens. It prompts a question, who am I?” she said, citing similar turning points after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Marina Shepelsky, an immigration attorney in nearby Sheepshead Bay who has been fielding hundreds of inquiries a day about how to get people out of Ukraine and Poland and into the U.S., said that for the first time ever, clients are demanding she speak Ukrainian. She apologizes.

“I was born in Kyiv … but my Ukrainian is atrocious,’” she said.

The request is more symbolic than practical.

“If you’re over 35” — which most of her clients are — “you definitely speak Russian,” she said. It was the dominant language of the Soviet Union, and the use of native languages was often discouraged.

But, Shepelsky said, younger immigrants who grew up in the post-Soviet era and those from western Ukraine are less likely to speak and understand Russian.

Ira Barytska, 33, is from the western Ukrainian city of Ternopil. She came to the U.S. in 2016 and works cleaning houses.

Ukraine is burying its dead. The bodies of service members killed in the conflict with Russia are returning to hometowns throughout the country. Residents pay last respects.

As the last rays of sunlight seeped out of the sky on a recent evening, she and a friend huddled in the cold watching their children play at the Brighton playground.

“We have our own culture, our own language,” said Barytska. “We are proud of it. We want to be our own country.”

Barytska’s mother and brother are still in Ukraine. As a 28-year-old male, he is barred from leaving. Barytska talks with them several times a day, and she prays for them at a Ukrainian church in nearby Manhattan Beach.

Her friend Alona Lensky, 34, is from Dnipro, a more Russian-speaking area in central Ukraine. She, too, has a brother there, as well as an uncle and grandfather.

Lensky doesn’t support the war, which she sees as “pointless, brother against brother.”

She said the war’s outcome won’t change day-to-day life for her relatives, who grow flowers in greenhouses outside the city. Some of them think surrender would be the most peaceful option — and Lensky agrees.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s virtual appearance before the U.S. Congress was just the latest in a series of rousing addresses.

“Kids are dying, regular people are being hurt,” she said. “Now your passport’s Russian — what difference does it make?”

Barytska doesn’t feel the same way at all. The two seldom discuss the war.

“I don’t fight with her,” Barytska said of Lensky, who arrived in the U.S. earlier and has helped Barytska get on her feet. “I like her because she’s a good person.”

For others the differences have been more pronounced — and the rifts unbridgeable.

Levitis, whose Facebook group Russian Insider has more than 17,000 members, said that overwhelmingly, people support Ukraine. “Ethnic Russians, Jews, everybody who came out of the Soviet Union — everybody’s pitching in, no matter what their viewpoints are, no matter where they’re from,” he said.

But since the war started he has had to suspend or kick out roughly 500 people for slinging insults, calling names and making derogatory comments.

“I would say it’s 50-50” Ukrainians and Russians on the list, Levitis said. “You have a lot of raw emotion on both sides.”

Wang Jixian of China lives in Odesa, Ukraine, and posts videos of his life in the war zone.

While the vitriol is worst on social media, real-life friendships have suffered, too.

Alla, a Jewish woman from Lviv in western Ukraine, has lived in Brighton Beach almost 40 years.

On a sunny, early spring afternoon she sat on a bench facing the sea with a friend, also from Lviv. They had just returned from donating money, clothes and medications at a Ukrainian church.

After her friend left, Alla said their husbands have stopped speaking to each other.

“She is very much on my side” in support of Ukraine, Alla said. “But her husband” — who is from St. Petersburg — “is very different.”

“I doubt he even knew that she went to the church,” Alla added.

Alla, who didn’t want to give her last name because of the sensitivity of the situation, had a falling-out of her own with her neighbor.

The two played cards and hosted each other for shish kabob dinners all last summer. But the neighbor, who was from Kharkiv in eastern Ukraine and whose husband served in the Soviet Army, supports Vladimir Putin.

On a phone call after the war started, it was clear the two saw things differently.

“I said, ‘Let’s not continue this conversation.’ She said, ‘But it’s not going to prevent us playing cards by the pool, right?’ And I said, ‘Yes, it is going to.’ Because to sit next to the enemy — excuse me — and talk about the weather is unacceptable.”

Immigrants identifying as Russian have also been caught in the middle.

Ksenia Kiseleva, 38, was born in Moscow and opposes the Kremlin. She used to work in Brighton Beach and her mom still lives here.

“The Russian people don’t want this war. Nobody supports it. It’s horrible what’s happening,” Kiseleva said.

But she is proud of her Russian culture and heritage.

“A lot of Russian people are now becoming very embarrassed to say they’re Russian,” she said. “I’m not embarrassed to be Russian.”

Kiseleva has fraying friendships on both sides — with a Ukrainian who has been aggressive to her, and with a Russian who defended Putin, saying he had no choice but to attack.

“We start to fight,” she said. “I start to cry. I can’t have those conversations.”

They stop talking, then start again, avoiding the topic. She doesn’t know how the disputes will end.

“Friendship is not based on political views,” she said. “But a war between your own people … I don’t think there is any excuse.

“I don’t want to lose any of my close friends,” she said, “but we’re going to see.”

Agrawal is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.