Texas militia sanctioned by sheriff seeks government support to halt flow of migrants

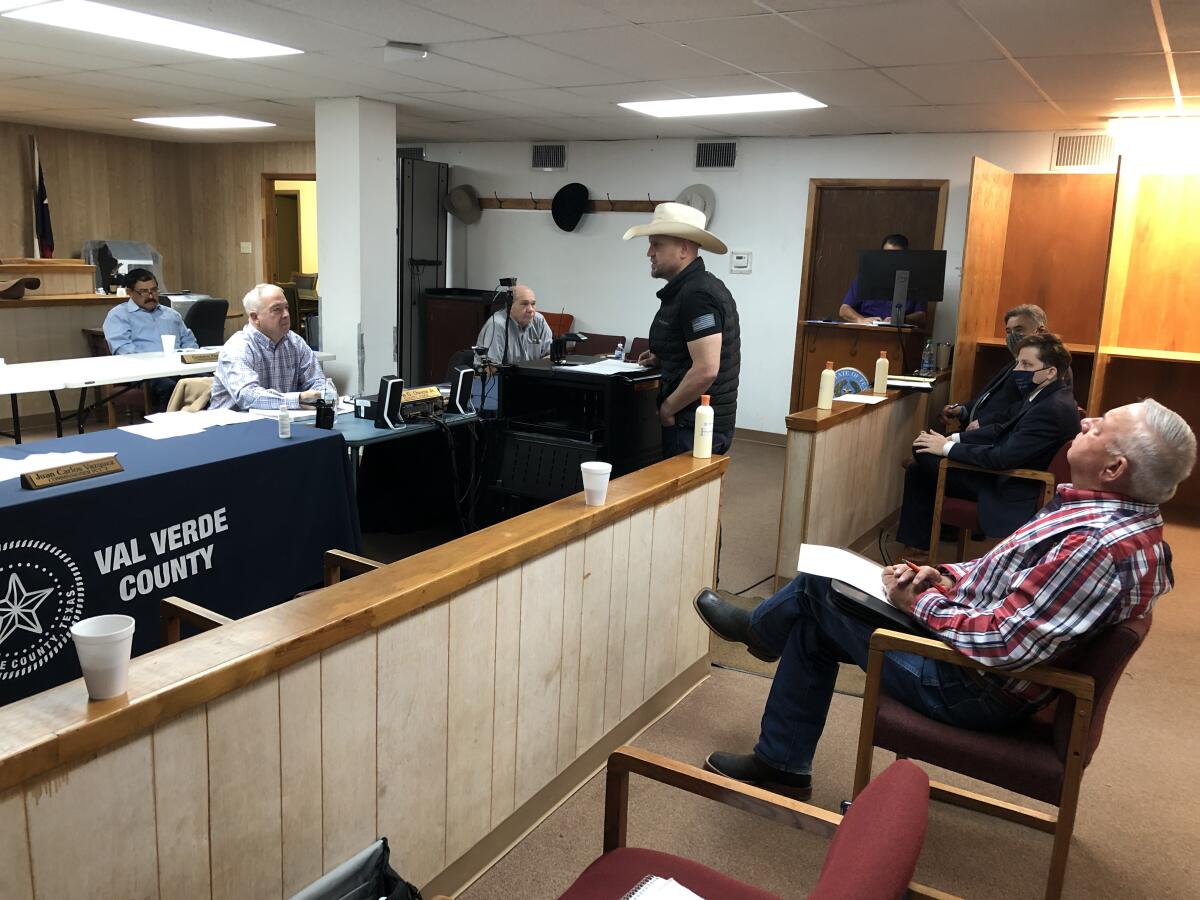

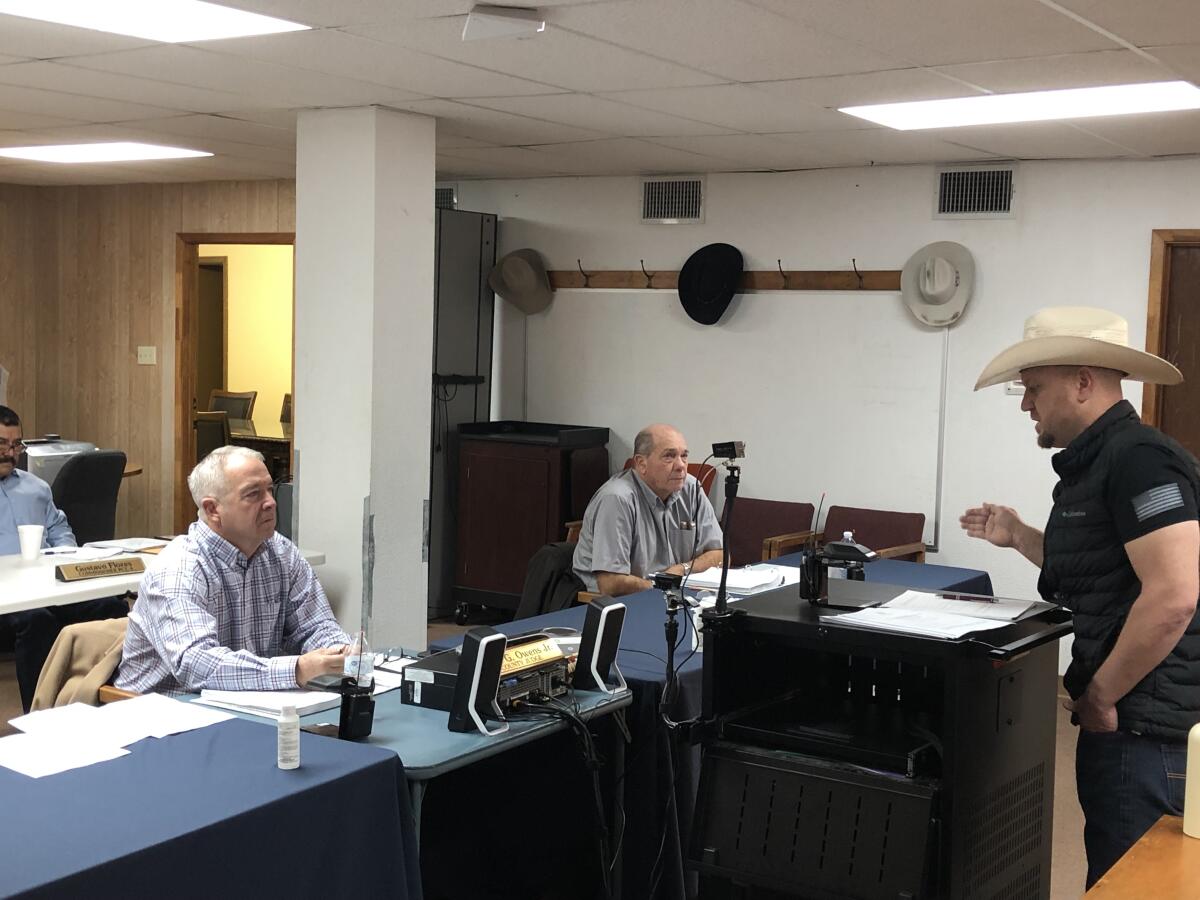

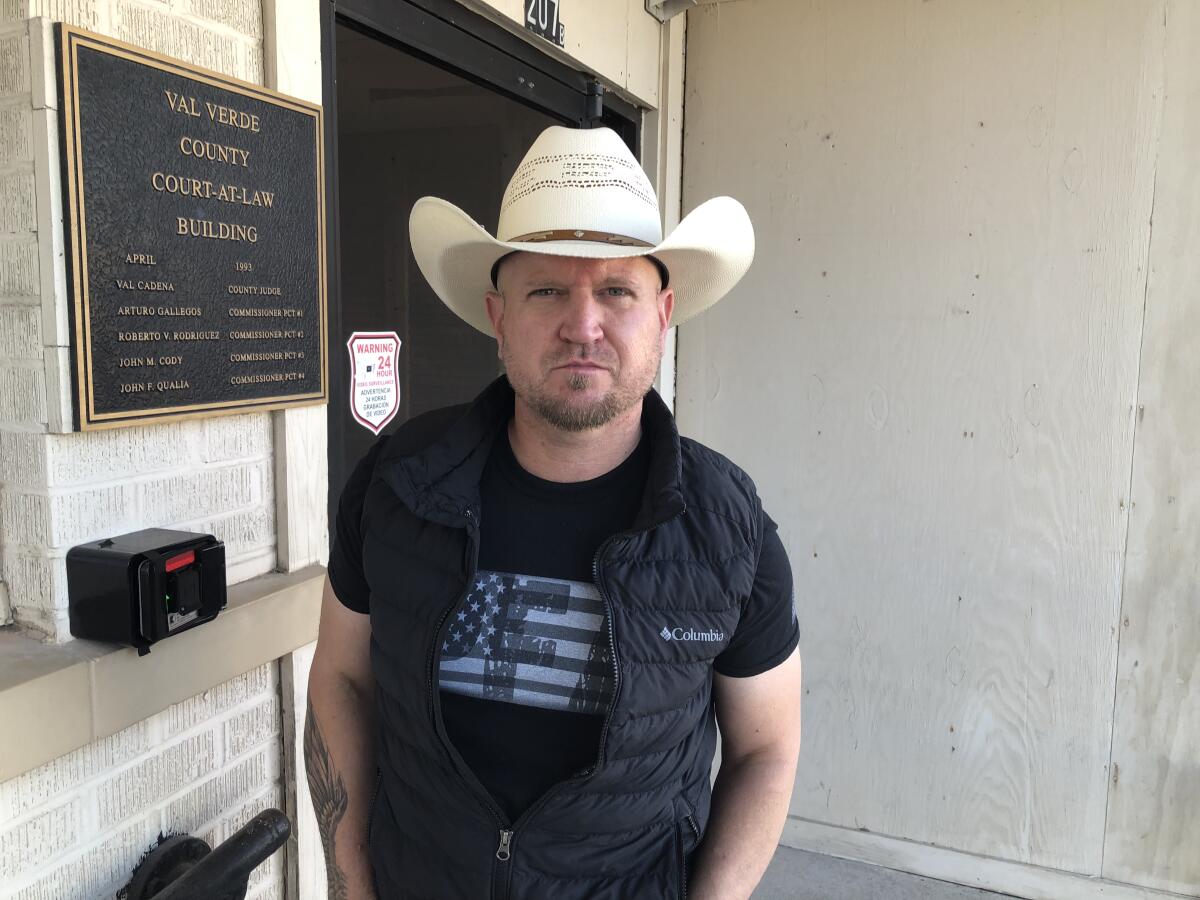

DEL RIO, Texas — The militia leader came before Val Verde County commissioners at their regular meeting in this border town 200 miles west of San Antonio wearing a straw cowboy hat, boots and a T-shirt emblazoned with the American flag.

He introduced himself as Samuel Hall, north Texas-based founder of Patriots for America. For the last two months, volunteers from his militia — which doesn’t disclose the size of its membership — had coordinated with the sheriff of neighboring Kinney County to stop illegal immigrants. The militia patrolled in shifts, funded by donations. They approached ranchers in Val Verde about running operations on their land too. Hall hoped to win commissioners’ blessing at Tuesday’s meeting.

“We are expanding our operations,” said Hall, 40. “The militia has been demonized pretty well by the left. My goal and my objective before you today commissioners is to let you know that our message is pure. We’re not a bunch of guys that have a hate rhetoric. We’re not a bunch of guys that beat our chest or have the wrong intentions or wrong message. We are a Christ-centered, faith-based organization. We’re a bunch of believers.”

Militias have staked out the border for decades, but Patriots for America has managed to do what many others have not: Patrol armed, with landowners’ permission, in concert with local law enforcement.

The militia arrived here after Gov. Greg Abbott declared the Texas border a disaster and launched Operation Lone Star last spring, allowing state troopers to arrest and jail migrants on misdemeanor trespassing charges. Since then, thousands of migrants have arrived, including a caravan of Haitians that overwhelmed U.S. Customs and Border Protection last fall, prompting criticism of some agents who were photographed on horseback chasing migrants.

Migrant deaths have increased in both counties this year. Sheriffs said there have been drownings in the Rio Grande and bodies recovered on ranches further north. Last week, the American Civil Liberties Union and nine other groups filed a complaint to the U.S. Department of Justice, requesting that it investigate Texas agencies and local governments involved in the operation. Among their concerns: County support for militias.

“Operation Lone Star goes hand in hand with white supremacist extremism including efforts to partner with vigilante groups,” said Kate Huddleston, a staff attorney with the ACLU, noting it had yet to receive a substantive response from the Justice Department.

Texas’ Brooks County and the Rio Grande Valley to the south have been popular smuggling routes for decades. Six months into 2021, deaths in the county had already reached 55, up from a total of 34 last year.

“We’re particularly concerned about violence due to the armed vigilante group presence and law enforcement’s willingness to work with them instead of ensuring that everyone in the county is safe,” Huddleston said.

She said the majority of the more than 2,300 arrests under the program have been made in Kinney County, a conservative, rural ranching community of about 3,500 people.

“The prosecutors are busy nonstop,” Sheriff Brad Coe said during an interview at his office last week in the county seat of Brackettville, about 130 miles west of San Antonio.

Coe served for 30 years with the Border Patrol and still has Donald Trump stickers on his desk. Coe said he stays in touch with Hall, that ranchers have allowed the militia on their land and appreciate them in town.

“When they go into the stores, restaurants, people love them. They say, ‘We appreciate what you do,’” Coe said.

Coe said when he started working with the militias, he received pushback from the Texas Department of Public Safety, causing concern the state would pull resources from the county.

Travis Considine, a spokesman for the state agency, said it didn’t support partnering with militias. But he said the department never threatened to pull resources from Kinney County.

“We do not want to work with [militias], but we do not control the sheriffs,” he said.

Val Verde County Sheriff Joe Frank Martinez also had reservations about working with Hall’s group.

Hall insists his militia is law-abiding. They vet members with background checks. When they encounter migrants, they use their cellphones to alert the sheriff. They don’t detain migrants, he said, which would be illegal.

“They can leave if they want,” Hall said, although migrants they encounter are usually too tired. “They’ve given up on their trek.”

Hall met Martinez twice before the commissioners’ meeting and asked the sheriff to approach local ranchers on his behalf. The sheriff said he talked to seven. “They don’t want them on their ranches” because of liability, he said.

At Tuesday’s meeting, Martinez looked on from the gallery as Hall appealed to the five commissioners, four of them Democrats.

“When we do come upon illegal immigrants, it is our goal to comfort them, not be mean, not be intimidating. We give them food, we give them water, we attend to any medical needs that they have,” Hall said, including three migrants they found a few nights earlier in Kinney County “very scared, very cold.”

“They had been walking for a month and a half from Nicaragua. In Spanish, the translation was they had been persecuted by their own country so much that this was the only path that they felt they could take.”

The increasing tension has rattled the Del Rio area and conservatives nationwide, who have made it their battleground for border policy just as residents prepare for hunting season, when they fear shootings may erupt.

He noted that he had met with the county’s chief executive the day before, Judge Lewis Owens Jr., a Democrat, who agreed the county was struggling to cope with the surge in migrants this year.

“People on both sides of the aisle are fed up. We don’t have the proper resources, we don’t have the proper infrastructure, to handle this crisis. So what do we do? Well, we have Texans like Patriots for America,” Hall said.

Hall choked up as he described how, after a Val Verde County rancher allowed them onto his property recently, they saw discarded migrant children’s clothes, shoes and a toddler’s life jacket. He said Coe supported the militia because of their “humanitarian message.”

“We don’t come in with any intent to hurt anybody. We don’t come in with any intent to cause any fights,” he said. “We’re here to make a positive difference, but we need your support.”

Militia member Kevin Caldwell, 58, a former business owner from north Texas, spoke next. He told commissioners he had just retired, bought an RV and was about to travel with his wife when Hall contacted him.

“I put all of my plans on hold to heed that call,” Caldwell said, insisting militia members are not “vigilantes.”

“Those volunteers are hardworking people like myself that are making sacrifices understanding that what’s going on down here is not right. We are a nation of laws and we need to enforce those laws,” he said.

Owens, a former developer and contractor, said commissioners wouldn’t be deciding the matter at Tuesday’s meeting, but noted that migrant flows into the area had not slowed.

“It’s becoming a bigger and bigger problem,” said Commissioner Robert “Beau” Nettleton, the lone Republican, who owns a landscaping company, runs a family ranch and had arrived chewing an unlit cigar. “There was a guy on my porch, a scout, charging his cellphone. We’ve got to do something on the north end of the county. Those ranchers are getting overrun. And these are not people looking for asylum.”

Commissioner Gustavo “Gus” Flores, who owns a hauling and trucking company, agreed.

Owens noted that days before, Abbott debuted the first stretch of state-built border wall to the east in the Rio Grande Valley. The county executive had been fielding calls ever since about what the state planned to build locally. On Friday, Abbott announced another $38.4 million in funding for the state’s border operation.

“The administration has completely abandoned the American people on this issue,” Nettleton said.

“Yes,” Hall whispered in the gallery.

Hall left the meeting feeling encouraged. Though the sheriff told him ranchers were not supportive, a couple were, he said, and “there were a few commissioners I spoke with who seem open.”

Owens, the county executive, was less optimistic.

“I don’t think they’re going to be needed in or welcomed in our county,” he said, although he conceded, “We agreed on just about everything we were talking about except them coming into our county.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.