BUSAN, South Korea — Son Eun-ji’s newborn son will begin the first months of his life in a sci-fi-like home in the middle of a sparse river delta that was until recently sprawling fields of scallions.

The young family will move early next year into an experimental project showcasing South Korea’s ambitions for the city of the future. Robots will patrol the streets, mow the grass and deliver packages. Homes will be powered by renewable energy, and excess electricity will be shared among neighbors or absorbed into the grid. Benches, streetlights and trash cans will be internet-connected and gathering data to optimize efficiency. Residents’ vitals will be monitored and an artificial-intelligence-equipped gym will offer health tips.

Sensors, meters and cameras inside and outside will hum in around-the-clock surveillance. The technology-laden “smart city” being built on the southern coast of South Korea epitomizes the daily bargain for most of humanity: the relinquishing of personal data and privacy in exchange for convenience, order and safety.

Every wrinkle of life will be monitored — except maybe fleeting thoughts and daydreams. Son’s boy, Logan, will grow up very differently from his millennial parents. They are gauging the wonders and misgivings of rapidly advancing technology, but Logan’s generation is being born into an already digitally interconnected reality where big data and artificial intelligence will shape his everyday existence long before he’s old enough to contemplate notions of privacy or give his consent.

The World They Inherit

This is the seventh in a series of occasional stories about the challenges young people face in an increasingly perilous world. Reporting was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center.

“The idea that you have any kind of anonymity is rapidly disappearing, in public spaces but also in private life,” said Steven Feldstein, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace who focuses on democracy and technology. “The way my kids now are being tracked, their medical information, the music they stream, what they watch, all of that is noted and recorded, and accessed in different ways.”

The trade-offs of this emerging world were foreshadowed by the COVID-19 pandemic, when cities and countries decided on how far to infringe on personal freedoms to protect public health. Some of the nations that pried most deeply into private lives to track infections managed to keep deaths low, curb rampant spread and prevent healthcare systems from being overwhelmed.

South Korean authorities relied on a panoptic software they had been developing to manage “smart city” projects — a dashboard to collect and analyze data to improve urban life. The platform was quickly repurposed into an epidemiological tool. It allowed contact tracers to target a person’s cellphone location data, credit card usage and movements in a matter of minutes. The rapid, meticulous tracking was central to the country’s widely celebrated success at pandemic control: Where the U.S. saw more than 240 COVID-19 deaths for every 100,000 people, South Korea lost just 8.

But as the planet turns to the reality of living with the virus, the long tail of the pandemic will also include an accounting and reckoning over the intrusive technology that was deployed. Logan’s future is unfolding as revelations about government surveillance on citizens, corporate spying and data mining by Facebook and other social media platforms have raised alarm over who wields the power of technology over the globe’s 8 billion people.

“The pandemic marks a real serious inflection point for a lot of this.... Who decides when COVID has gone away? If it’s something that never really truly goes away, those technologies and those systems may never truly go away either,” said Jathan Sadowski, a research fellow in the Emerging Technologies Research Lab at Monash University in Australia. “As history shows, we very rarely go back to the moment before. Once new doors have been opened, people are reticent to close them.”

The question facing Logan and his parents — along with governments, tech innovators and rights groups — is how to keep the same technology that drives the benefits of “smart city” living from jeopardizing civil freedoms. When the streets are watching and the walls are listening, is what you’re getting in return really worth it?

::

Son, 35, got a taste of the rewards of opening up her life to strangers when she started a travel blog after quitting her job as a nurse around 2015.

As her blog gained popularity, she was offered free meals, complimentary hotel stays and an all-expenses-paid trip to Switzerland. It was a worthwhile trade. Documenting aspects of her life and sharing it online came to feel almost second nature. A couple of years ago, she began posting vlogs on YouTube, including some of life’s most intimate moments — when she got engaged, when she found out she was pregnant, when she broke the news to her mother, tears welling in her eyes.

The ad seeking people to move into a “smart city” project in western Busan seemed not far off from the way she’d been living, despite the extensive technological surveillance it would entail. She was already using a smartphone and a fitness tracker bracelet, and had installed a dash cam on her car, a common practice in South Korea.

She eagerly applied to move in with her sister, mother and soon-to-be husband, an English teacher originally from California, to join a five-year experiment on futuristic living in exchange for free housing. The family will be one of 56 households moving into what is eventually planned to be a development of 30,000 households.

“We’re not blindly giving up private information. We’re providing it because there’s a benefit to us,” Son said. A friend of hers balked at the idea that residents’ weight would be logged — but Son responded that she wasn’t bothered because she isn’t overweight. “I’m not sure exactly what data is going to be collected. I’m a little concerned about CCTVs and filming and motion detection inside the home — but they said at least it won’t be inside the bathrooms.”

Son’s budding family will be part of South Korea’s pledge to spend $8.5 billion of public money by 2025 in what has become a global digital race between tech giants and governments to create cities of tomorrow. In addition to revamping and building cities domestically, South Korea says it will export “smart city” technologies and platforms around the world, including proposed projects in Uzbekistan, the Philippines, Kenya and Indonesia.

Compared with their new home, the modest apartment Son and her husband, Nathaniel Kebbas, currently live in might as well be in the dark ages — the couple don’t have a smart speaker, security cameras or an internet-connected thermostat, and are still mulling over a baby cam for their son. As much as the technology that awaits them will be a major adjustment, Kebbas, 34, said as long as data aren’t used to coerce him into doing something he doesn’t agree with, he is comfortable living amid cameras and sensors. When he was a teacher back in Salinas, his classrooms were always monitored by cameras, he said.

“I’m an open book. Sure, in exchange for the living experience you want to collect some data, why not?” he said. “I feel like there is an exchange. Like a job, you exchange freedom for compensation. There is a trade-off.”

In September, Son went to sign the paperwork for their move-in. Listed over several pages, single-spaced, was the information she and her family were agreeing to share with the city’s operators and tech vendors: the grams of food waste they throw away; their blood pressure, blood count and cholesterol levels; the exact times they enter and exit their front door.

Signing on dotted line after dotted line, she felt a bit of uneasiness creep up at the long list of private information she was agreeing to share. But she swallowed it and quickly flipped through the pages, and in minutes, it was done.

“There is nothing you can do except embrace the future,” Kebbas said. “We’re starting off in a place where my son is going to be secure. It’s the first five years of his life, and it’s safe.”

::

For about a month in early 2020, Kim Jae-ho, then a researcher at the Korea Electronics Technology Institute, worked around the clock to retool the “smart city” data hub he’d been helping to create for South Korea’s fast-growing COVID-19 case control.

“All this data is one of the most important resources of a city,” he said. “We were developing technology to make that data flow seamlessly [into] ... a hub that collects, processes, stores, utilizes and serves up a city’s data using the internet of things, the cloud, big data and artificial intelligence.”

When the new epidemic control system was being rolled out, Kim began casually polling cabdrivers. What did they think of the government having almost immediate access to credit card data and cell tower information to track individuals to contain those infected with the coronavirus? He was surprised they were receptive and even welcoming of the tracking, if it meant they’d be alerted to potential infections.

“This system, more than any harm it may have caused, saved lives by preventing the disease’s transmission,” said Kim, now a professor at Sejong University in Seoul. “On the flip side, you could see it as privacy being sacrificed, but there was societal consent.”

South Korea wasn’t the only government that repurposed “smart city” systems to collect data to battle COVID-19. Singapore and China launched extensive tracking efforts. In the U.S. and Europe, health authorities partnered with Palantir Technologies Inc., a big-data analytics company that has sold its software for terrorism investigations, immigration enforcement and predictive policing, to track and contain coronavirus cases.

Before the pandemic, the idea of “smart cities,” popularized by companies like IBM and Cisco in the mid-2000s to market technology to solve urban problems, encountered resistance in parts of the world. A Google-affiliated project to develop a waterfront in Toronto that proposed heated sidewalks and autonomous vehicles was scrapped in 2020 after residents questioned who would own the data collected and who would profit. But when intrusive technology was deployed against COVID-19, most countries did not have the time for a public conversation.

Such emergencies “can be moments where governments roll out new invasive forms of data collection and it just becomes the new normal, because in moments of crisis there’s a deeper allowance in terms of public trust and legal authority,” said Ben Green, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan’s Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy. “There’s less of a sense of pausing for reflection, because there doesn’t feel like there is time when dealing with a global pandemic.”

Governments sought to assure citizens that heightened surveillance systems would track and manage only the spread of COVID-19. That line was blurred in some places. In Singapore, an uproar arose after police were given access to information from a voluntary contact tracing app to investigate suspected criminals. Dahua, a Chinese company that produces heat-mapping cameras to detect individuals with fevers, has dozens of public contracts in California. The firm, which also offers facial recognition software that can make racial identifications, has won contracts from the Chinese government for surveillance in Xinjiang, home to the persecuted Muslim Uyghur ethnic minority.

China is one of the most heavily surveilled nations in the world. Its companies and cities are also among the most ardent and advanced in developing, deploying and exporting such technologies. More than half of the world’s “smart city” projects are in China, according to a 2020 report by the United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

In South Korea, the city of Bucheon raised concerns this year over a publicly funded project to develop an artificial intelligence program using facial recognition to track individuals’ movements from camera to camera. The city said the technology would lessen the workload on contact tracers who were manually analyzing hours of footage. South Koreans had been living with QR code check-ins at restaurants and contact tracing with cellphone and credit card data, but the specter of facial recognition technology proved unsettling.

The city was flooded with angry calls and protesters camped out in front of city hall. Officials said the anxiety was misplaced because the software, still planned for completion in January, would follow only a known infected person rather than be used as a dragnet on the general public.

Kang Myoung-gu, professor of urban and regional planning at the University of Seoul and director of its Smart City Research Center, said such technologies, driven by tech corporations whose profits are at stake, won’t easily be reined in.

“For politicians, they like the symbolism and the big promise that this one thing will offer this rose-colored future. For the vendor companies, it’s a business opportunity, a money stream. But what about the citizens and residents?” he said. “A city is a public realm; there needs to be high accountability and responsibility. But it’s driven by construction and IT interests, and loudmouthed politicians.”

Sadowski of Monash University in Australia said the pandemic may leave a lasting effect on people’s acceptance of technological surveillance. “That floor has been raised, collectively. Things we would have balked at not that long ago become normal,” he said. “What happens when it’s no longer necessary and it just sticks around?”

::

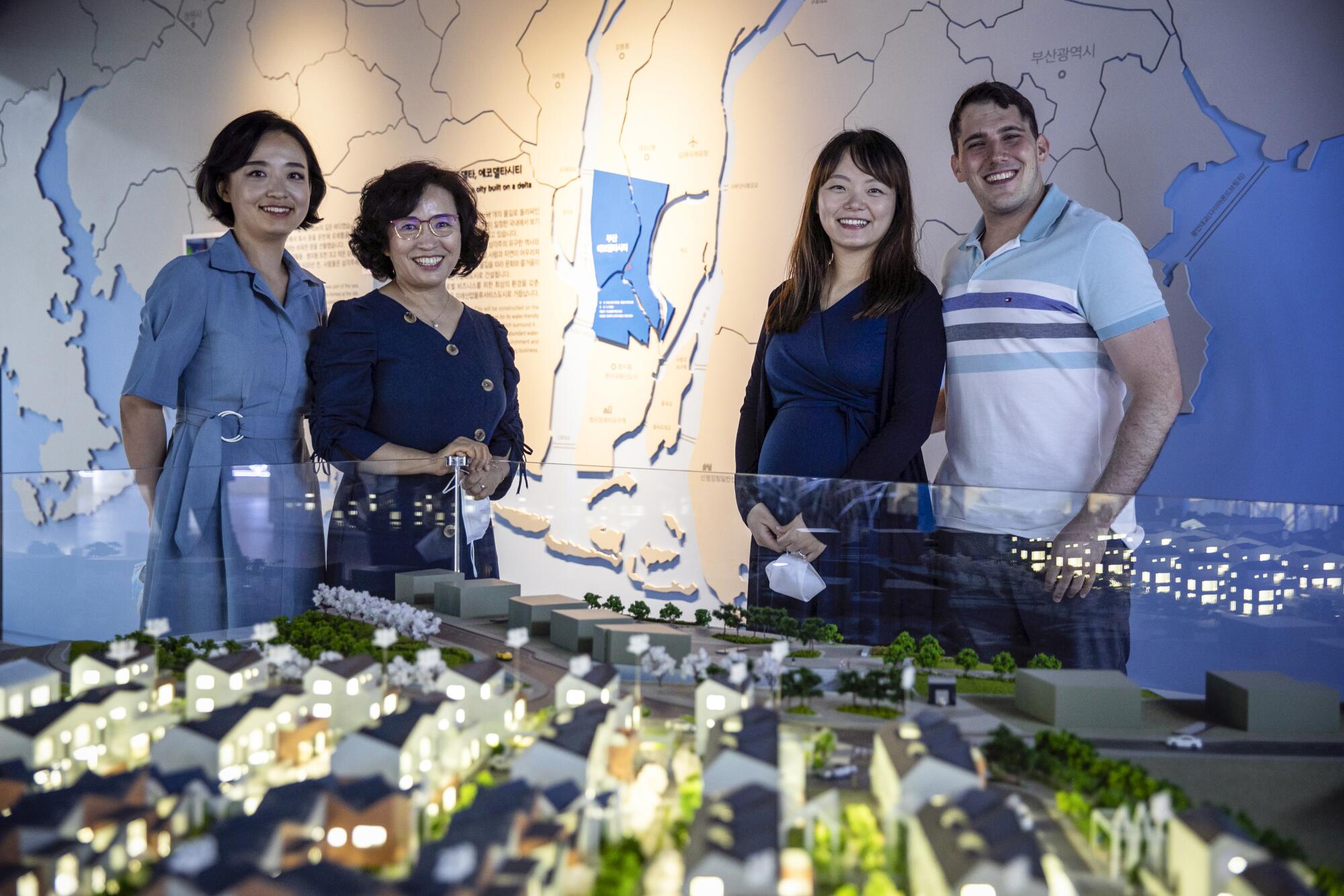

On a drizzly day last summer, Son’s family drove to a showroom near the site where their new home was being built. Inside, displays highlighted the technologies they will soon be living with.

Kebbas played around with a virtual fitness tool, shaped like a giant smartphone screen, that used a camera to analyze his physique and corrected his form. It told him he had good flexibility and above-average agility, but below-average core stability and poor balance. “I wasn’t entirely sure about having this collected, but professional athletes, they have that,” he said. “I can think of myself like that.”

Nearby, his mother-in-law stood in front of a smart mirror that cast her in different outfits that she may be able to purchase without having to leave her bedroom. A “master plan” for the village on one side of the showroom was full of lofty, specific promises: three years of added lifespan with improved health, 46% reduction in traffic accidents, 25% decrease in major crimes.

Son said she was excited to be at the vanguard of various innovations, even if the utility, necessity and privacy implications are still being worked out. As she thinks about what lies ahead for her young son, though, she has some misgivings about the technology, the environment and the future of humanity.

“It is incredibly helpful and convenient, but I do worry humans may become slaves to artificial intelligence,” she said. “I’d hope humans are at the core, and technology is the dressing. It scares me to think humans may become the dressing.”

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

(This is the seventh in a series of occasional stories about the challenges young people face in an increasingly perilous world. Reporting was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center.)

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.