Missionaries kidnapped in Haiti, U.S. religious group says

MEXICO CITY — A notorious Haitian gang linked to many kidnappings and killings in the Caribbean nation has emerged as the prime suspect in the weekend abduction of 17 missionaries and their relatives, comprising 16 U.S. citizens and one Canadian.

Those seized were five children, seven women and five men, according to a statement Sunday from the Ohio-based Christian Aid Ministries. The kidnappings rattled the large community of church workers and nonprofit organizations from around the world, including California, working in the impoverished nation.

The Associated Press in Port-au-Prince, the Haitian capital, quoted a Haitian police inspector, Frantz Champagne, saying that an infamous criminal organization known as the 400 Mawozo gang was behind the kidnappings.

The gang is said to control swaths of the town of Ganthier, east of the capital, where the kidnapping reportedly took place.

Marie Michel Verrier, a police spokeswoman, declined to comment.

From the Philippines to El Salvador, there is a long history of American missionaries facing violence while trying to spread their religions abroad.

Haiti in recent months has seen a surge in kidnappings for profit, including abductions of entire groups traveling in buses, vans and cars. Most of those seized have reportedly been released, typically after payments of ransoms.

Most kidnap victims are Haitians, though some foreigners — including French clergy members — have been among those seized in recent months.

On Sunday, the State Department confirmed the kidnapping of the 17 but declined to provide details.

“We have been in regular contact with senior Haitian authorities and will continue to work with them and interagency partners,” a department spokesperson said. “The welfare and safety of U.S. citizens abroad is one of the highest priorities of the Dept. of State.”

The 17 were seized Saturday while on a trip to visit an orphanage, Christian Aid Ministries said.

“Join us in praying for those who are being held hostage, the kidnappers, and the families, friends and churches of those affected,” the group said in a statement. “Pray for those who are seeking God’s direction and making decisions regarding this matter.”

The fate of the abducted individuals remained unclear late Sunday in Haiti, where criminal gangs exert broad control in a nation long plagued by political instability and suffering from the aftermath of various natural disasters.

A deeply divided interim administration has been running the country since the July 7 assassination of President Jovenel Moise, who was gunned down by a commando squad in a crime that remains unsolved. Five weeks later, an earthquake killed more than 2,200 people in the country’s southwest, an event that seemed to usher in a period of additional unrest.

Three days after the assassination of Haiti President Jovenel Moise, it’s still unclear who ordered it and who did it. His security team is scrutinized.

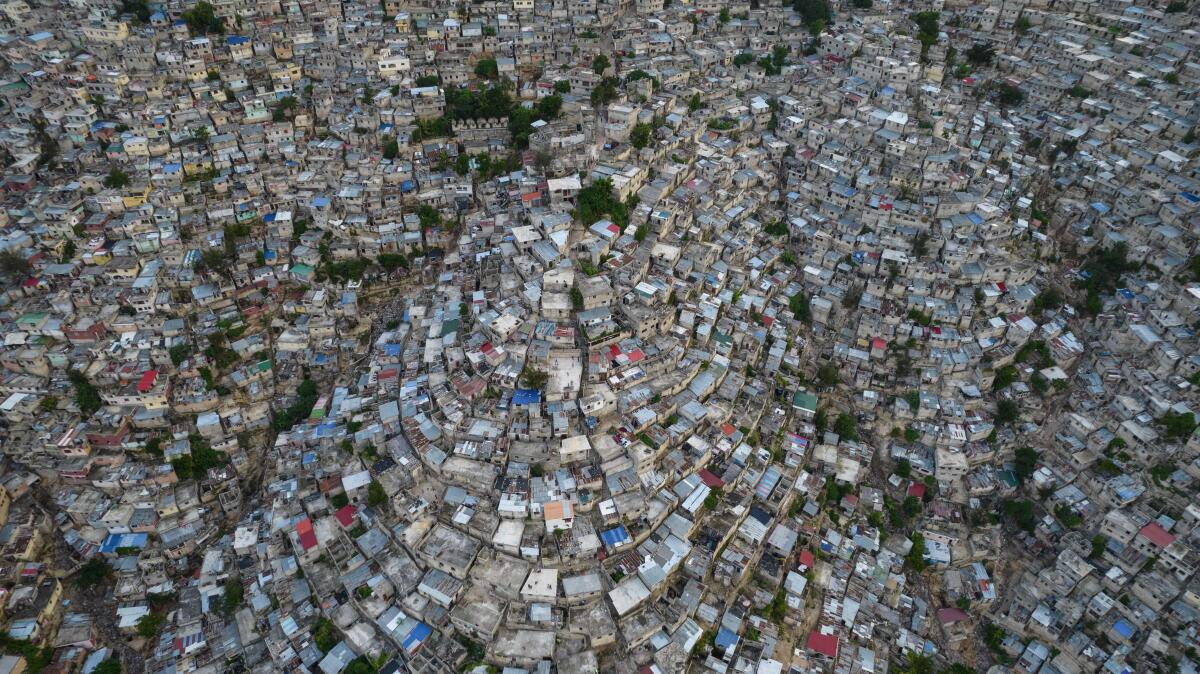

“Since August 2021, the gangs have grown more arrogant and occupy more area in the country,” said Pierre Espérance, executive director of RNDDH, a Haitian human rights network. “No space is left today in the metropolitan area” of Port-au-Prince, he added.

Civil groups in Haiti demanded the release of the kidnapped missionaries and their families.

“We call for the liberation of the persons kidnapped, whether American citizens or of other nationalities,” said Gedeon Jean, who heads the Port-au-Prince-based Center for Analysis and Research in Human Rights, reported Agence France-Presse. “The police have proven incapable of confronting the gangs, which have become better organized and which control more and more territory.”

Christian Aid Ministries is one of hundreds of international religious groups, many with U.S. ties — and many with California chapters and volunteers — that operate nonprofits, shelters, schools and missionary programs in Haiti. Battered in recent years by earthquakes, hurricanes and violence, Haiti has come to depend on religious organizations and nonprofits to deliver basic services that the government doesn’t provide.

Last month, armed gunmen stormed a Port-au-Prince church building and killed a deacon. Earlier in the year, the 400 Mawozo gang kidnapped a group of nuns and priests as the faithful traveled between Port-au-Prince and Ganthier.

The situation has gotten so perilous that even humanitarian organizations are turning to the use of armed guards, said Margarett Lubin, country director of CORE Response in Haiti, the Los Angeles-based group founded by the actor Sean Penn following the earthquake that leveled much of the capital of Port-au-Prince in 2010.

“This kidnapping thing is just hitting closer and closer,” Lubin said. “It’s not like you hear about it and you think, ‘Oh maybe they were involved in something.’ No, today it’s your friend, tomorrow it’s your friend’s friend, the next day it’s your friend’s sister. It’s just getting closer and closer to home.”

The doctors’ abductions dealt a major blow to attempts to control criminal violence that has threatened disaster response efforts in Port-au-Prince.

Employing armed guards is a difficult decision for aid organizations, she noted.

“NGOs usually do not use armed guards, but now you have to think twice. Do you not use it because you are humanitarian worker, or do you think about saving your life and those of other people with you?” Lubin said. “Like now, when I have people come in to visit, yeah, we get armed guards and the right vehicle to be able to move them around.”

One of the biggest problems for CORE is moving equipment from the capital to the southern earthquake zone, because gangs control Route Nationale 2 as it leaves Port-au-Prince in the Martissant area.

“Every time you send a team out, you are taking a chance,” Lubin said. “When Martissant is closed, the whole south is cut off.”

Speaking via Zoom from Port-au-Prince on Sunday, Lubin said she has a staffer whose father was kidnapped and killed, another whose father was taken hostage for three weeks and released.

“Now with the 17 missionaries, including kids who have been kidnapped, people are going to make a lot of noise,” she said. “People are upset. People are outraged. But it’s a daily thing.”

Lubin said gangs have gone into churches to kidnap pastors in the middle of their sermons, or schools to snatch students and staff. Every morning, she says, she has to consult numerous security firms that have popped up by the dozens as the crime grew worse.

“I have to care for the safety of my staff, so every morning I go to different groups just to make sure you’re not getting fake news,” she said. “Is it safe to go out, is it not safe, do you strategize, how to arrange staff movement. It’s really exhausting and terrifying.”

The apparent targeting of church groups has sounded alarm bells for the many religious institutions working in the country.

“We’ve been through so much in Haiti, but this year it is the first time the church is now becoming a target,” said Guenson Charlot, an evangelical Christian who co-pastors Discipleship Evangelical Church in Cap-Haïtien on the country’s northern coast. “Is this something God is telling the church in Haiti?” asked Charlot, who is also president of Emmaus University, a Christian institution in Haiti.

His co-pastor and wife, Claudia Charlot, said she was praying for peace.

“It’s difficult to carry on your ministry in this climate,” she said, adding that her church and many Haitian evangelicals in the country were planning a three-day fast as a means of asking God for a cooling of tensions.

Based in Millersburg, Ohio, Christian Aid Ministries was founded in 1981 and today has workers and volunteers across the globe.

In the United States, the group has sponsored dozens of roadside billboards proclaiming, “Beyond reasonable doubt — JESUS IS ALIVE!” and inviting onlookers to dial a toll-free number to talk to a hotline of evangelists.

Christian Aid Ministries pulled its missionaries out of Haiti in 2019 after violence and political strife, but sent them back in 2020. One of its main efforts in Haiti is a “sponsor a child program,” where it promises to cover the costs of covering textbooks and meals for five school kids for a monthly $65.

The Christian Aid Ministries website says the program has served 9,000 students across 52 schools.

Last year, Christian Aid Ministries faced criticism after allegations surfaced of a former employee sexually assaulting boys. The nonprofit settled a lawsuit and said it had given $420,000 to victims.

McDonnell reported from Mexico City and Mozingo and Kaleem from Los Angeles. Times staff writer Tracy Wilkinson in Washington, D.C., and special correspondent Harold Isaac in Port-au-Prince contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.