The U.S. delves into the pain inflicted on Indigenous communities through boarding schools

Ground-penetrating radar this year revealed hundreds of unmarked graves at former residential schools in Canada.

The harrowing discovery — remnants of a government policy that sought to eradicate Indigenous cultures by separating an estimated 150,000 children from their families from the 19th century through the 1990s — prompted reaction from religious leaders and public officials worldwide.

In the U.S., Interior Secretary Deb Haaland wept when she saw the headlines from Canada. She is a member of the Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico, and her maternal grandparents were among the children subject to a similar policy on this side of the border. The Interior Department, which she now runs, oversaw hundreds of boarding schools for more than a century.

Native American leaders and community members have repeatedly called on the U.S. government to take accountability for these family separations, which historians describe as part of efforts to break up tribal control of territory. In late June, Haaland, who became secretary this year as part of the Biden administration, instructed the department to prepare a report on the boarding school policy and its ramifications by April 2022.

“Survivors of the traumas of boarding school policies carried their memories into adulthood as they became the aunts and uncles, parents, and grandparents to subsequent generations,” Haaland wrote in a memo on the initiative. “The loss of those who did not return left an enduring need in their families for answers that, in many cases, were never provided.”

Haaland’s initiative was commended by the National Congress of American Indians, which represents 574 federally recognized tribal nations. However, the organization maintains that a truth commission — in the style of those in many countries that have sought to atone for their past — is needed to move forward, one that includes support for survivors and their descendants.

Here are more details about the issue:

What were the boarding schools in the U.S. like, and what did they aim to achieve?

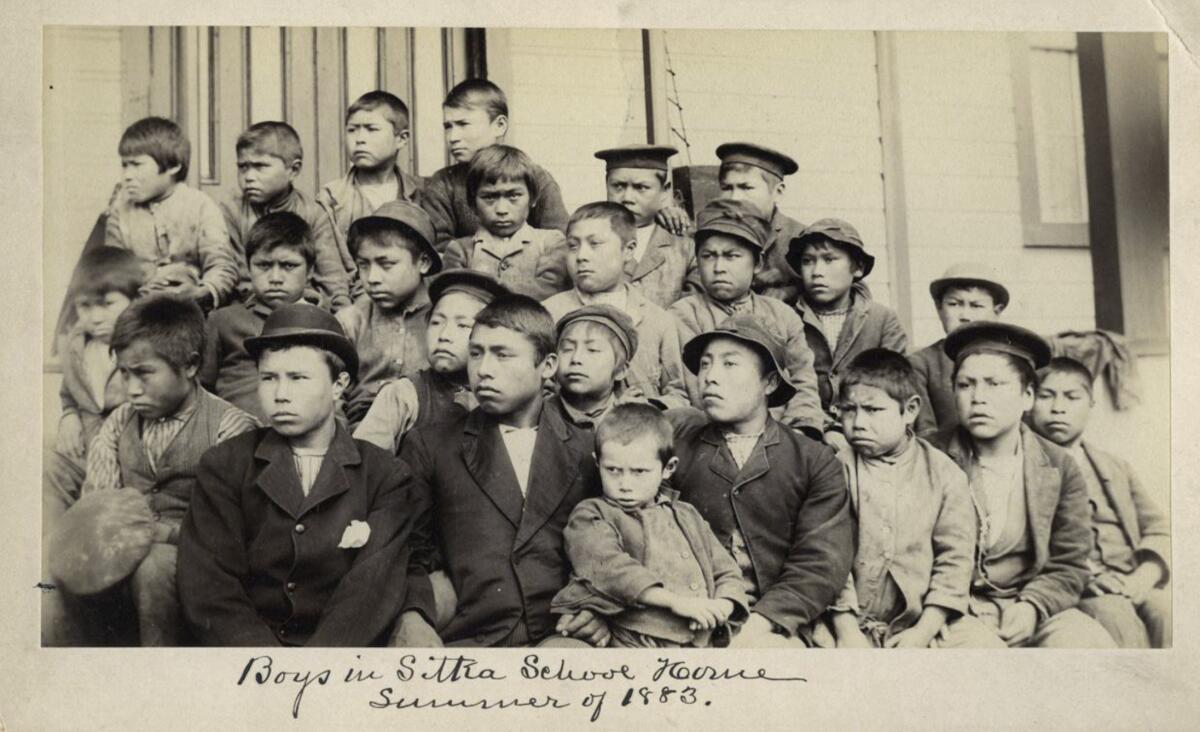

According to historians, from the 19th century through the 1960s, hundreds of thousands of Indigenous families were forced to send their children to boarding schools run by the federal government or religious groups. For those on reservations, coercion ranged from having their food rations denied to being imprisoned for refusing to give up their children.

The precise number of campuses remains unknown, said Denise Lajimodiere, a historian, educator and founding member of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, a nonprofit group formed in 2012 to raise awareness about the policy.

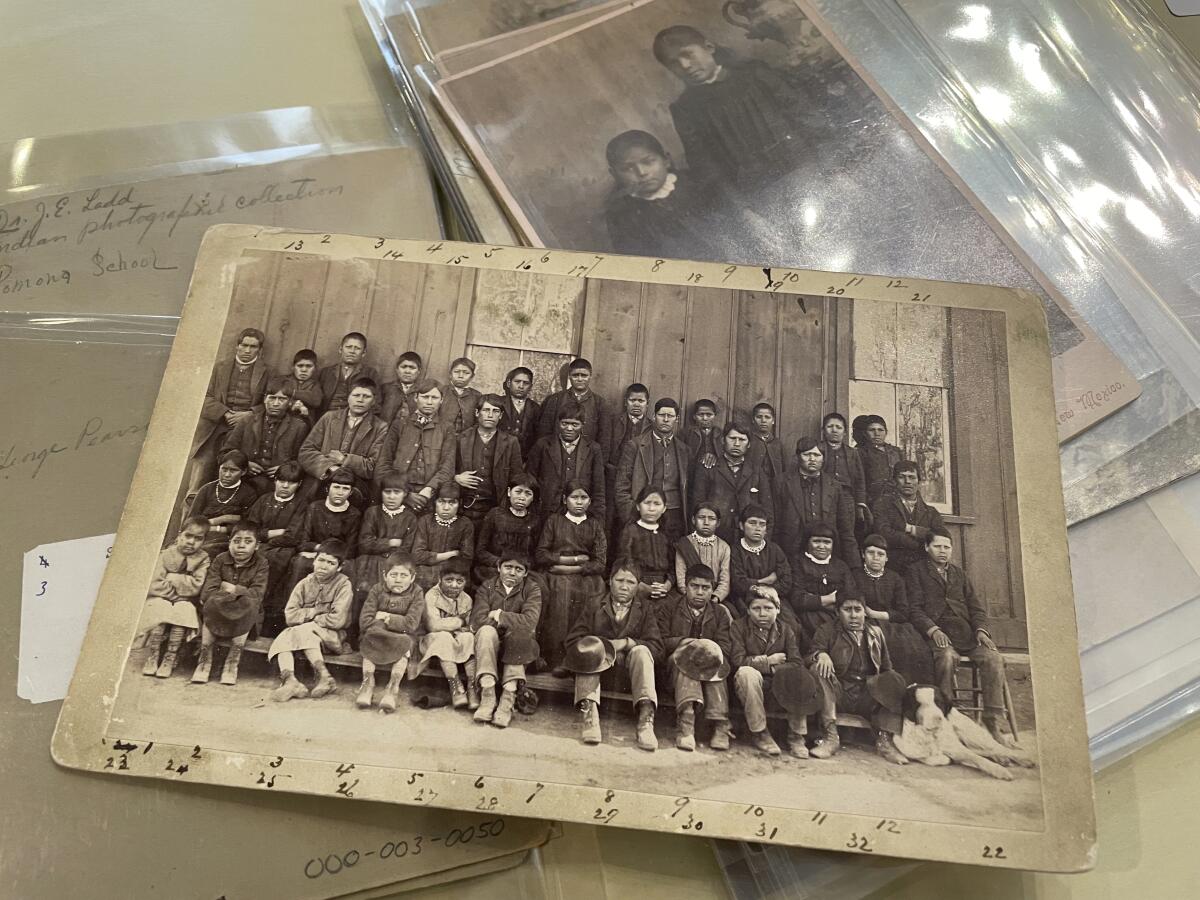

But after years of work — including reviews of university archives, government offices, church records, museums, historical societies and personal collections — she and fellow researchers have identified 406 boarding schools across 30 states.

Before those institutions were established, Lajimodiere said in a phone interview, U.S. territorial expansion prioritized the extermination of Indigenous groups. Then, federal policy shifted toward control through forced assimilation.

Capt. Richard H. Pratt, a Civil War veteran who later participated in military offensives against Native Americans, played a key role in the transition, Lajimodiere said. When he was deployed to Ft. Marion in St. Augustine, Fla., Indigenous prisoners of war became part of Pratt’s experiment to “civilize” those he considered “savages.”

The captives, who’d been shipped hundreds of miles away from home, spent part of the day doing manual labor. The rest of their time was devoted to studying English and Christian religion. In 1879, Pratt established the first government-run boarding school for Indigenous children in Carlisle, Penn., using his experiences in Florida as a template.

Though the experiences of former students varied, Lajimodiere said, the schools were set up to strip Indigenous children of their heritage, making it easier for them to be subsumed under mainstream culture. Children were often forced to cut their hair and given new names. They were also forbidden to speak their language or engage in cultural practices.

The boarding schools, often underfunded, tended to rely on child labor, ranging from campus maintenance to farm work. One of the women Lajimodiere interviewed for her book “Stringing Rosaries: The History, the Unforgivable, and the Healing of Northern Plains American Indian Boarding School Survivors” was a student at St. Joseph’s Indian School in Chamberlain, S.D., in the 1960s. As a girl, the woman had worked putting little plastic rosaries on cards used for fundraising.

Many children were sent to campuses hundreds of miles away from their families.

“Parents were considered the enemy. The theory was that if you took the child away from their parents, you could change the entire culture in one generation,” Joel Spring, professor emeritus at City University of New York and author of the book “Deculturalization and the Struggle for Equality: A Brief History of the Education of Dominated Cultures in the United States,” said in a phone interview.

That isolation created conditions ripe for emotional, physical and sexual abuse, historians said. While corporal punishment was common when the boarding schools were established, Indigenous children had few, if any, options.

Some schools allowed students to call home. But when they did, their overseers often hovered over them, warning them not to disclose anything unpleasant to their parents.

Another woman Lajimodiere interviewed for her book said she was routinely molested by a priest at St. Joseph’s Indian School. When she complained about pain in her genitals, that same priest drove her to the doctor. She was 6 years old.

What are the goals of the initiative and other efforts?

The Haaland initiative’s primary goal is to identify boarding schools and possible student burial sites. The Interior Department also aims to establish the interred children’s identities and tribal affiliations. It has also pledged to compile records about the boarding school program.

The National Congress of American Indians approved a resolution to build on the initiative, asking the Interior Department to conduct “non-destructive, non-invasive” ground imaging at boarding schools to determine how many students died there. The group also called on Congress to establish a “Truth and Healing Commission” that would last at least three years.

The group hopes for a process like Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was set up as part of a class-action settlement. This commission spent six years gathering testimony from 6,500 witnesses across the country. The Canadian government also provided 5 million school-related records, now housed at the University of Manitoba and most of which are available to the public.

Many boarding schools were affiliated with religious groups. How have their leaders responded?

News of the unmarked graves also prompted a response from Pope Francis, who issued a tweet expressing his “closeness to the Canadian people, who have been traumatised by [the] shocking discovery.”

But the country’s Indigenous groups want a formal apology.

Given that nearly three-quarters of Canada’s state-funded residential schools were run by Catholic missionaries, a papal apology was one of the 94 recommendations made by its commission. To date, this demand continues to go unmet. In contrast, the Anglican, Presbyterian and United churches have offered apologies for their involvement.

In 2018, Canadian bishops said the pope could not personally apologize. Critics noted that Francis apologized for the colonization of Latin America during a trip to Bolivia in 2015.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau reached out to the Vatican this summer, urging the pope to apologize to Indigenous Canadians on Canadian soil. The pontiff is scheduled to meet with residential school survivors in December.

So far, these plans do not extend to the U.S., where at least 14 religious denominations, including the Roman Catholic Church, were involved in the boarding school system.

How can the U.S. government address the intergenerational trauma caused by these institutions?

Spring, an enrolled member of the Choctaw Nation in the U.S. whose work as a forensic historian involved investigating residential schools in Alberta, Canada, stressed that Indigenous parents in both countries were discouraged from visiting their children.

“No one really thought about the psychological consequences of ripping children away from their families,” he said.

In collaboration with the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition and the National Indian Health Board, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Rep. Sharice Davids (D-Kan.) issued a letter to the Indian Health Service in mid-August requesting culturally appropriate support for affected communities, especially those who might experience trauma from revelations that emerge from the initiative.

Other lawmakers signed the letter recommending the creation of a hotline that boarding school survivors and their descendants could use to access mental health services, much like Canada’s Hope for Wellness Help Line, which offers assistance across the country.

“Healing will look different for everyone,” Lajimodiere said. “Maybe it’ll involve psychiatrists, maybe it’ll involve spiritual ceremonies — there’s no one way. Everyone must decide that for themselves.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.