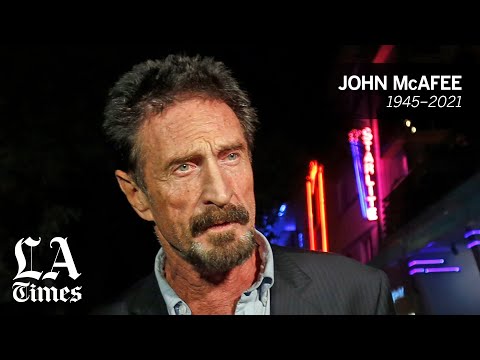

Antivirus pioneer John McAfee found dead in prison after extradition ruling

After a decade living on the run and at odds with police and governments, antivirus software pioneer John McAfee was found dead in a jail cell near Barcelona. He was 75.

John McAfee, the antivirus software pioneer turned anti-government cryptocurrency promoter and frequent fugitive from the law, was found dead in his prison cell in Spain on Wednesday.

The last 15 years of the grizzled tycoon’s life were marked by run-ins with — and flights from — police and governments across the Western Hemisphere. In media interviews and posts on his own social media accounts, he cultivated the air of a louche renegade, sometimes shirtless, frequently on a boat, often with a gun nearby, holding out against tyrannical government conspiracies.

McAfee, 75, announced his most recent exile in 2019, writing on Twitter that he had not paid taxes in eight years. “Every year I tell the IRS, ‘I am not filing a return, I have no intention of doing so, come and find me,’” he added in a video post.

That same year, a Florida court ordered McAfee to pay $25 million in a wrongful-death suit to the estate of his former neighbor in Belize, Gregory Viant Faull. McAfee fled the Central American nation in 2012, after police in Belize announced that he was a “person of interest” in Faull’s apparent murder.

In October 2020, he was arrested by Spanish authorities on tax evasion charges filed by the U.S. Justice Department, and was imprisoned outside Barcelona awaiting a decision on extradition until his death.

Spain’s National Court on Monday ruled in favor of extraditing McAfee, who had argued in a hearing earlier this month that the charges against him were politically motivated and that he would spend the rest of his life in prison if he was returned to the U.S.

The court’s ruling was made public Wednesday and could have been appealed. Any final extradition order would also have needed approval from the Spanish Cabinet.

Nishay Sanan, the Chicago-based attorney defending him in those cases, told the Associated Press that McAfee “will always be remembered as a fighter.”

“He tried to love this country but the U.S. government made his existence impossible,” Sanan said. “They tried to erase him, but they failed.”

Nanette Burstein, director of the documentary “Gringo: The Dangerous Life of John McAfee,” described McAfee as both brilliant and “scary,” with an ability to “manipulate people to view him the way he wanted them to.”

“He can cause harm to people, and a lot of people get sucked into his charisma,” Burstein said. “And he preys on the vulnerable, quite frankly.”

John David McAfee was born at a U.S. Army base in Gloucestershire, England, in 1945, and spent his early years in Virginia, graduating from Roanoke College in Salem, Va., with a degree in mathematics in 1967. Fresh out of college, he went to work at NASA in 1968, then built a career as a programmer jumping between the major corporations of the day, including Xerox and Siemens.

McAfee displayed a brash techno-libertarianism from his earliest days in the public eye — though he focused on human viruses before turning to their digital analogs. He founded his first splashy initiative, the American Institute for Safe Sex Practices, while working at Lockheed Corp. in 1986.

The computerized dating service required new applicants to take an HIV antibody test, and allowed only the HIV-negative to join. Members were issued a card certifying their viral status and were asked to refrain from sexual contact with nonmembers to remain in good standing.

“Everybody is concerned about this issue,” McAfee said to the San Diego Union-Tribune in 1987. “I came up with the idea to help people deal with this crisis in an intelligent manner.”

Then McAfee turned his attention to the business that would make his a household name: computer viruses.

He became a go-to expert on the new phenomenon bedeviling computer users and drew criticism as a virus hype man, drumming up fears of new digital plagues every year to sell more software.

Inside the walls of his company, McAfee Associates, he oversaw a corporate culture nearly as eccentric as his later life. The company was built on a shareware model, encouraging users to download antiviral software for free and pay later. Early employees carried out Wiccan rituals during the lunch hour, practiced sword fights and Shakespearean dialogue, and ran a secret competition to have sex in as many parts of the office as possible — with double points awarded if the act occurred during business hours, according to the San Jose Mercury News in 2001.

John McAfee’s crazy story coming to the big screen

McAfee became a multimillionaire when his company went public in 1992 and left the following year, saying he wanted out before things got too corporate. With his new fortune, he moved to the mountains — first to a complex in the Rockies above Colorado Springs, and then to a collection of properties in Arizona and New Mexico. There, he founded a company called Tribal Voice, whose central product PowWow was an instant messaging service for Windows. He sold that company for $17 million in 1999.

During this period, according to the Mercury News, McAfee lived a life of yoga and motorsports, riding ATVs, jet skis and lightweight aircraft around his New Mexico ranch.

In 2006, McAfee encountered the first of the legal troubles that would mark the rest of his life. After two guests died in a flying accident at his ranch that year, a relative sued McAfee for negligence. Two years later, with his fortune reduced to $4 million through failed investments, according to Bloomberg, McAfee sold his U.S. holdings and moved to an island in Belize, where he surrounded himself with heavily armed guards and prostitutes.

On a Sunday in November 2012, McAfee’s neighbor Faull was found dead in his home with a single gunshot wound in the back of his head. Local police announced that they considered McAfee a “person of interest,” and he went to ground, feeding commentary of his flight to Wired reporter Joshua Davis, who relayed McAfee’s testimony that he had buried himself in the sand with a cardboard box over his head when the police first came to his home.

Less than a month later, reporters at Vice magazine meeting with McAfee for a clandestine interview accidentally revealed his location — a resort in Guatemala — in the metadata of a digital photo posted on the publication’s website. Soon after, Guatemalan police arrested McAfee. He successfully fought against extradition to Belize, and was deported to the U.S. within a week.

Back in the States, McAfee did not choose to lie low. In 2015 McAfee was arrested on charges of driving under the influence and handgun possession in his new home of Alabama, then kicked off a run for president on a platform of disbanding the border patrol and redirecting its budget to supporting immigrants, among other ideas.

Two years after that, McAfee woke up in the middle of the night and sprayed his home with bullets “naked but for an ammunition belt,” according to a report in Newsweek. The incident led to McAfee’s discovery that his wife, Janice, a former sex worker whom he had met in South Beach, Fla., upon his return to the U.S., had been plotting with her former pimp to kidnap McAfee.

The pair remained together, and Janice accompanied McAfee on the next leg of his journey outside the law. In 2019, McAfee declared that he was living in exile on his yacht at sea while the U.S. government sought him for tax evasion.

In July, he went to Cuba, where he encouraged the government to use cryptocurrency to evade the ongoing U.S. trade embargo. Later that month, he was arrested in the Dominican Republic for trying to enter the country with high-caliber guns and ammunition.

At the same time, he was campaigning again for president and took to Twitter frequently to promote cryptocurrencies — including one of his own coinage, a token called “Epstein Didn’t Kill Himself,” in reference to the conspiracy theories surrounding the death in prison of Jeffrey Epstein in August 2019.

The tax hammer dropped in October of the following year. McAfee was arrested in Spain on suspicion of tax evasion, following an indictment by the U.S. Department of Justice, on the same day that the Securities and Exchange Commission sued him for promoting sales of cryptocurrencies while being paid to promote them.

In March of this year, while McAfee sat in Spanish prison awaiting a decision on his extradition to the U.S., federal prosecutors in New York also indicted him on fraud and money laundering charges in relation to his social media promotion of cryptocurrencies.

Representatives of the Justice Department, Commodity Futures Trading Commission, Securities and Exchange Commission and FBI did not reply to inquiries.

Burstein, the documentary maker, likened McAfee to former President Trump in his ability to court media attention while dodging accountability. “Nothing sticks to them no matter what they’re accused of, or what crimes they’ve committed, or what outrageous things they’ve said. The more outrageous, the better,” she said.

Times staff writers Andrew Mendez and Brian Contreras contributed to this report. The Associated Press was used in compiling this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.