The world’s greatest cardsharp reveals all

A Las Vegas legend, Steve Forte is revered by sleight-of-hand magicians and casino experts as the most skilled person ever to deal, shuffle and generally manipulate a deck of cards.

LAS VEGAS — Fremont Street, once the world capital of swank, used to be Steve Forte’s turf.

But on a spring day, he was just another face in a crowd, snaking through two relics of downtown Las Vegas, Binion’s and the Four Queens casino. No one bothered the man many consider the greatest card handler who ever lived.

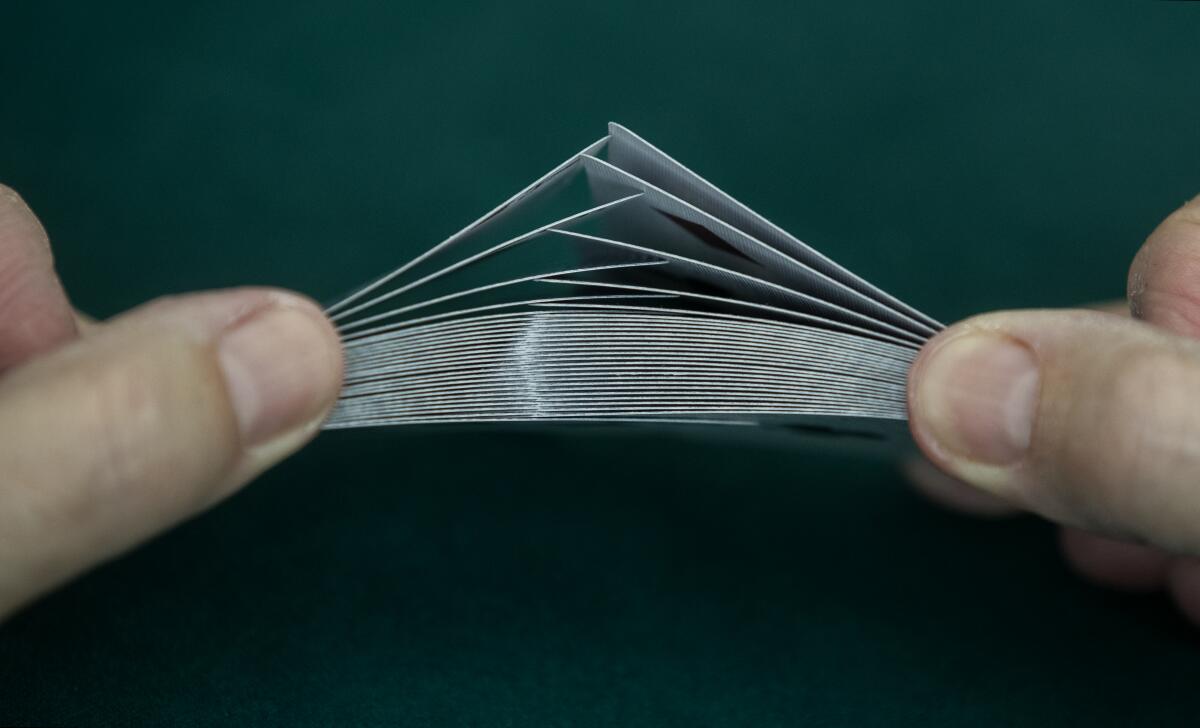

Within the world of casino experts and magicians, Forte handles a deck of playing cards the way Roger Federer wields a tennis racket. Not just among the best, but the best, full stop. In his hands, cards appear to shuffle but remain in perfect order. Cards apparently dealt from the top of the deck are taken invisibly from the bottom.

After years of being a reclusive figure, the 65-year-old Forte has published “Gambling Sleight of Hand,” his life’s work of underground card moves in a two-volume book of nearly 1,100 pages. Among sleight-of-hand aficionados, the book was a once-in-a-lifetime sensation: Even at $300, the first printing of 1,000 sold out in one week.

On this day, Forte agreed to visit places he doesn’t have much use for now. But soon enough, he showed his skill, making jaw-dropping observations about the games unfolding around him.

His book is a fitting coda to a career that screams to be a biopic (in fact, a script of Forte’s life is being shopped around). He went from dealing prodigy, to one of the youngest casino managers ever in Las Vegas, until he ventured to the other side of the law and made millions — “ripping and tearing,” as card cheats say. Then he became one of the most in-demand casino security consultants in the world.

Said Jamy Ian Swiss, a noted writer on sleight-of-hand magic: “Anybody writing a movie about a professional cheater would never put in a character like Steve Forte. People wouldn’t believe him. They think he’s some kind of Superman. This isn’t realistic. The guy can’t be all these things. But he is.”

::

The streets of Newton, Mass., where Forte grew up, had fire hydrants painted red, white and green. A proudly Italian neighborhood. For Newton’s working class in the 1960s, working hard wasn’t always enough. Many played the numbers.

“They were always looking for the impossible dream,” Forte recalled. “And it was a complete suckers game.”

Forte’s father, John, was a construction worker who made extra cash Friday nights picking up people from a Dunkin’ Donuts parking lot and driving them to a clandestine dice game. He compulsively played the numbers, figuring that if he lost four games in a row, he was certain to hit it big on the fifth.

One day when Forte was a teenager, he and his father swung by a restaurant where gambling went on in the cellar. Seated at one table was an old-timer shuffling cards.

Noticing Forte was interested, the man motioned him over. “Let me show you something, kid,” he said.

The old-timer flashed the top card of the deck. An ace. He began shuffling. A lot. Miraculously, the ace remained on top. Forte was floored. The old-timer not only exerted perfect control over the cards, he did it so suavely.

An obsession took hold. In time Forte realized these games his father played weren’t pure games of chance — the more you’d play, the more likely you’d lose. It was a mathematical certainty. But he understood something those hoping to luck their way to a better life did not; you could improve your odds.

Teenage Steve visited the library and checked out the seminal books on gambling at the time: Edward Thorp’s “Beat the Dealer” and John Scarne’s “Guide to Casino Gambling.” He never returned the books. He was hired at his local American Legion hall and dealt cards during charity casino nights. The kid was a natural.

Even after accepting a junior college scholarship to play basketball, the glitz and flashing lights of casinos beckoned. There was only one place to go. At 20, Forte left school, packed everything he owned into a ‘74 Camaro and drove west.

::

Las Vegas in the late 1970s was a city where the mob had outsized influence.

“How do you feel about unions?” asked one job interviewer.

“I don’t even know what a union is, sir,” Forte responded. “I just want to deal craps.”

“Right answer, kid.”

Interview over. Forte was hired on the spot. Two hours after turning 21, he dealt his first game.

His bosses recognized a talent that belied Forte’s age. When a casino veteran discovered Forte never attended blackjack school, the veteran was astounded: “You cradle that deck like a mother cradles her baby.”

Off work, Forte was a gambler himself, preferring blackjack and low-limit seven-card stud. Forte played nearly every day for seven years, and had the mathematical formulas — when to play, when to fold — down cold. He coupled that knowledge with what’s called advantage play: exploiting biases in gameplay that nudge the odds back toward the player’s favor.

Although advantage play is legal, the line between it and cheating can appear blurry. If a blackjack dealer accidentally flashes his card, the gambler has every right to use that information. There’s nothing illegal about mentally tracking high cards over many rounds of blackjack — card counting. But most casinos can kick you out without cause.

“Ninety-nine-point-nine percent of advantage players are genuinely trying to stay on the right side of the law,” said Jason England, a friend of Forte’s and a gaming consultant.

Forte assembled a team who’d scout the casino floor, hoping to find a dealer handling cards a certain way. They’d play that table, and if the stars aligned, that dealer might unintentionally reveal the hole card.

Another example: In a game of blackjack, dealers would peek at the hole card if a high card was showing, to check if it was blackjack. In bending the hole card back, the high card would bend in the other direction, causing it to subtly warp and reflect light in a slight but distinctive way. When the dealer presented the deck to cut, Forte would cut exactly one card above the convex card. There’s a good chance he now has a 10 or an ace.

The playbook Forte’s team employed grew more sophisticated. They’d look for any subtle asymmetry in the back design of playing cards to track high cards. They’d strap electronic card-counting devices to their legs in blackjack games, a practice allowed at the time. These tactics involved information available to all players, so they were considered legal, relying more on perceptiveness than chicanery.

The irony was Forte’s star within the casino industry — his day job — was on the rise. He became casino manager at the Sundance Hotel & Casino at just 28.

When playing, he used an alias — Michael Panaggio — always volunteering to spell his last name to make it more believable. Even so, the Nevada Gaming Control Board caught on. In 1982, authorities raided a table at a Reno casino where Forte’s team was playing. They accused him of cheating. Forte showed what he was actually doing — cutting to that imperceptibly bent card.

Was this illegal? There was no statute against it. They struck a deal: In exchange for Forte demonstrating some of his moves for security experts, he’d plead guilty to misdemeanor trespassing.

To the Gaming Control Board, Forte was biting the hand that fed him. He kept playing, and in 1984 the board revoked his work card. Forte could no longer work at any casino in Nevada.

His livelihood gone, a switch flipped in Forte.

A reporter journeys across Santa Monica in search of a story about a louche moment in the tony city’s history.

“Once I made the decision to go for the money, I never thought twice about it. I was too young and immature, and I knew I was out of line,” Forte said. “They were accusing me of being a cheat anyways, so what was the difference?”

Las Vegas history is filled with inventive cheaters. Hustlers attached mirrors, called shiners, to carefully placed cigarette packs or casino chips, in hopes it would reflect a dealer’s hole card. A more sophisticated version was a periscope-like contraption built into a lowball glass, where the gambler could stare into their drink and glimpse the card with a mirrored ice cube.

Some schemes had a Rube Goldberg-ian complexity.

Say a blackjack dealer asked Forte to cut the cards. As Forte lifted the deck, he quickly thumbed up the side like a flipbook. A teammate standing behind Forte recorded the move with a camera hidden in a sports bag. He wore a cowboy hat to hide antennas boosting the radio signal.

The footage was transmitted to a van outside, where an accomplice watched a replay in slow motion. He’d read back the next 10 cards to another accomplice on the casino floor with an earpiece, who’d visually cue Forte what cards were coming up.

Atlantic City, 1987. As Forte played blackjack, an accomplice nearby quietly read the order of the cards dealt into a mini-cassette recorder. After several hands, the accomplice dashed to a payphone and relayed the sequence to a room upstairs, where it was run through a computer program to determine the optimal hands to play.

When it came time to shuffle, the dealer, who was in on the scam, would “false shuffle”—keeping the sequence of cards intact. Now the team knew when to hit, stand and double down. Forte said he made out with $100,000.

The team was caught. Agreeing to plead guilty to avoid a drawn-out appeals process, Forte asked the judge to let him serve his sentence before the upcoming birth of his son. He ended up serving two months for third-degree theft, half in maximum security and half in a work-release program.

Forte then became a security consultant full time and his company, International Gaming Specialists, became the go-to expert for casinos worldwide. Ironically, casinos that Forte and team once cheated were now paying him upward of $25,000 for a consult.

In the COVID-19 era, my 12-year-old played more video games than ever. What kind of parent was I to allow this? But then I talked to experts.

He was known mostly in the casino world until he appeared on the 1996 Fox television show “The Hidden Secrets of Magic,” even though Forte doesn’t consider himself a magician.

He closed his demonstration with the center deal, a notoriously difficult move, in which Forte apparently dealt four kings from the middle of the deck. It was the first time Forte’s card-handling abilities were exposed to a national audience. Even master magicians had never seen anything like it.

So years ago when a friend of Penn Jillette, the talking half of Penn & Teller, offered to take him to Forte’s house, Jillette jumped at the chance.

Jillette vividly recalled Forte demonstrating “the scoot,” throwing dice in such a manner so that the top number of one die stayed on top, even as the other die tumbled. “It looked like it was bouncing but was actually sliding,” Jillette said. “That delicacy of movement, and the hundreds of hours represented in learning that movement just struck me with awe.”

Then Forte broke out the playing cards. “I had my face down there, four inches from where his hands were. There was no chatter, no eye contact, nothing else for me to think about,” Jillette said. “I’m just trying to see what he’s doing with his fingers. I could not do it.”

When Forte self-published “Gambling Sleight of Hand” in February 2020, Jillette bought the book for himself and Teller. It’s now in a third printing.

::

The Sin City of yore — the Rat Pack roaming the Copa Room at the Sands, casinos run by mobsters — has largely vanished into desert dust.

In a way, so too has Forte. Most of his friends from the heyday have moved away. Forte now considers himself retired, though he continues to consult now and then.

Forte has lost some hand strength and can’t handle a deck as smoothly as he did in his 30s. He misses it.

“It’s one of the few hobbies I truly treasured,” he said. ”This one was dear to me.”

Still, his eye for spotting discrepancies — unconscious mistakes casino dealers make that a cheater might exploit — remains tack sharp.

At the Four Queens Hotel and Casino on Fremont Street, Forte watched blackjack dealers go through the motions. Within five seconds, Forte noticed how one dealer held her deck in such a way that the corner edges were exposed.

Forte stopped in front of a roulette table. He pointed out how metal deflectors on the wheel would influence the speed of the ball. By tracking the ball speed and the wheel’s spin rate, Forte said, he could predict where the ball might land (yes, you can bet while the wheel is spinning).

Counting off in quarter seconds, he determined this roulette wheel took 1.75 seconds to make one revolution. He also noticed the ball tended to drop in a certain area. If the wheel were a clock face, that would be between 12 and 3.

That, Forte said, is where he’d bet. The dealer spun the wheel and sent the ball rolling. The ball bounced and clattered, eventually landing on black 28 — exactly in the part of the wheel Forte predicted.

Pang is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.