Video shows 13-year-old Adam Toledo wasn’t holding gun when shot by Chicago police

CHICAGO — Body-camera video released Thursday after public outcry over the Chicago police shooting of a 13-year-old boy shows the youth appearing to drop a handgun and begin raising his hands less than a second before an officer fires his gun and kills him.

A still frame taken from Officer Eric Stillman’s jumpy nighttime body-camera footage shows that Adam Toledo wasn’t holding anything and had his hands up when Stillman shot him in the chest around 3 a.m. March 29. Police, who were responding to reports of shots fired in the area, say the teen had a handgun on him before the shooting. In Stillman’s footage, the officer shines a light on a handgun on the ground near Adam after shooting him.

The release of the footage and other investigation materials comes at a sensitive time, with the ongoing trial in Minneapolis of former Officer Derek Chauvin in the death of George Floyd and the recent police killing of another Black man, Daunte Wright, in a nearby suburb.

Before the Civilian Office of Police Accountability, an independent board that investigates all shootings by police in Chicago, posted the materials on its website, Mayor Lori Lightfoot called on the public to keep the peace, and some downtown businesses boarded up their windows in anticipation of unrest.

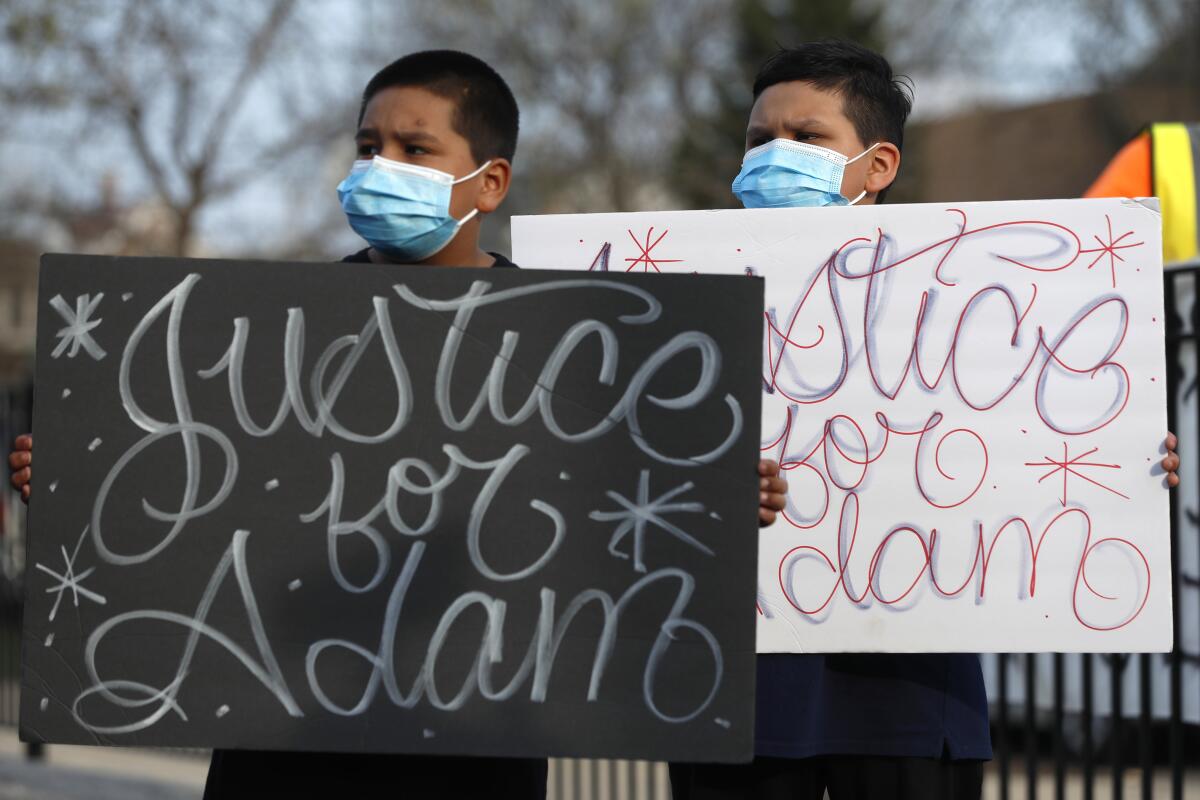

Small groups of protesters gathered at a police station and marched downtown Thursday night, but there were few signs of widespread demonstrations in the city.

“We live in a city that is traumatized by a long history of police violence and misconduct,” Lightfoot said. “So while we don’t have enough information to be the judge and jury of this particular situation, it is certainly understandable why so many of our residents are feeling that all-too-familiar surge of outrage and pain. It is even clearer that trust between our community and law enforcement is far from healed and remains badly broken.”

Nineteen seconds elapsed from when Stillman exited his squad car to when he shot Adam. His body-camera footage shows him chasing the boy on foot down an alley for several seconds and yelling, “Police! Stop! Stop right f— now!”

As Adam slows down, Stillman yells, “Hands! Hands! Show me your f— hands!”

Adam then turns toward the camera, Stillman yells, “Drop it!” and midway between repeating that command, he opens fire and Adam falls down. While approaching the wounded teen, Stillman radios for an ambulance. He can be heard imploring the boy to “stay awake,” and as other officers arrive, Stillman says he can’t feel a heartbeat and begins administering CPR.

In a lengthy email, Stillman’s attorney Tim Grace said Adam left the officer no choice but to shoot.

“The juvenile offender had the gun in his right hand … looked at the officer which could be interpreted as attempting to acquire a target and began to turn to face the officer attempting to swing the gun in his direction,” Grace wrote. “At this point the officer was faced with a life threatening and deadly force situation. All prior attempts to deescalate and gain compliance with all of the officer’s lawful orders had failed.”

Adeena Weiss-Ortiz, an attorney for Adam’s family, told reporters after the footage and other videos were released that they “speak for themselves.”

Weiss-Ortiz said it’s irrelevant whether Adam was holding a gun before he turned toward the officer.

“If he had a gun, he tossed it. The officer said, ‘Show me your hands.’ He complied. He turned around,” she said.

Bills moving forward in the state Legislature were applauded by an array of civil rights and police reform groups.

The Chicago Police Department typically doesn’t release the names of officers involved in such shootings this early in an investigation, but Stillman’s name, age and race — he’s 34 and white — were listed in the investigation reports that the Civilian Office of Police Accountability released Thursday.

Weiss-Ortiz said she looked into Stillman’s history and found that “he had no prior discipline, no prior events.”

Lightfoot, who along with the police superintendent called on the independent board to release the video, urged the public to remain peaceful and reserve judgment until the board completes its investigation. Choking up at times, she decried the city’s long history of police violence and misconduct, especially in Black and Latino communities, and said too many young people are left vulnerable to “systemic failures that we simply must fix.”

She also described watching the video as “excruciating.”

“As a mom, this is not something you want children to see,” she said.

In addition to posting Stillman’s video, the review board released footage from other body-worn cameras, four third-party videos, two audio recordings of 911 calls and six audio recordings from ShotSpotter, the system that alerted police to gunshots in that area of Little Village, a predominantly Latino and Black neighborhood on the city’s West Side.

Adam, who was Latino, and a 21-year-old man ran when confronted by police, and Stillman shot the boy once in the chest after a chase during what the department described as an armed confrontation. The 21-year-old man was arrested and booked on a misdemeanor charge of resisting arrest.

As civil rights advocates called for justice and police accountability over Daunte Wright’s death, his family asked people also to remember his life.

The review board initially said it couldn’t release the video because it involved the shooting of a minor, but it changed course after the mayor and police superintendent called for the video’s release.

Lucky Camargo, an activist and lifelong resident of Little Village, decided not to watch the video. But neighbors described it to her as “an execution.”

“This was wrong,” she said. “I didn’t need to watch the video to make that assessment on my own. I don’t feel there was any justification to shoot someone.”

Footage of the shooting had been widely anticipated in the city, where the release of some previous police shooting videos sparked major protests, including the 2015 release of footage of a white officer shooting Black teenager Laquan McDonald 16 times, killing him.

Before the Stillman video’s release, some businesses in downtown Chicago’s Magnificent Mile shopping district boarded up their windows. Lightfoot said that the city had been preparing for months for a verdict in the Chauvin trial and that it had activated a “neighborhood protection plan” ahead of Thursday’s release.

“It happens now that these circumstances are sitting next to each other,” she said.

Adam’s mother described him as a curious and goofy seventh-grader who loved animals, riding his bike and junk food. The Toledo family issued a statement urging people to avoid violent protests.

“We pray that for the sake of our city, people remain peaceful to honor Adam’s memory and work constructively to promote reform,” the family said.

Before the video’s release, Lightfoot and attorneys for the family and city said in a joint statement that they agreed that in addition to the release of the video, all investigation materials should be made public, including a moment-by-moment compilation of what happened that morning.

“We acknowledge that the release of this video is the first step in the process toward the healing of the family, the community and our city,” the joint statement reads. “We understand that the release of this video will be incredibly painful and elicit an emotional response to all who view it, and we ask that people express themselves peacefully.”

The Chicago Police Department has a long history of brutality and racism that has fomented mistrust among the city’s many Black and Latino residents. Adding to that mistrust is the city’s history of suppressing damning police videos.

The city fought for months to keep the public from seeing the video of a white officer shooting Laquan 16 times in 2014, killing him. The officer was eventually convicted of murder. And the city tried to stop a TV news station from broadcasting video of a botched 2019 police raid in which an innocent, unclothed Black woman wasn’t allowed to dress herself until after she was handcuffed.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.