Singapore says its contact-tracing data can be used for criminal investigations

SINGAPORE — Singapore’s COVID-19 contact-tracing program is facing renewed concerns over privacy after a government minister told lawmakers that data collected through the program could be used for criminal investigations, despite earlier assurances to the contrary.

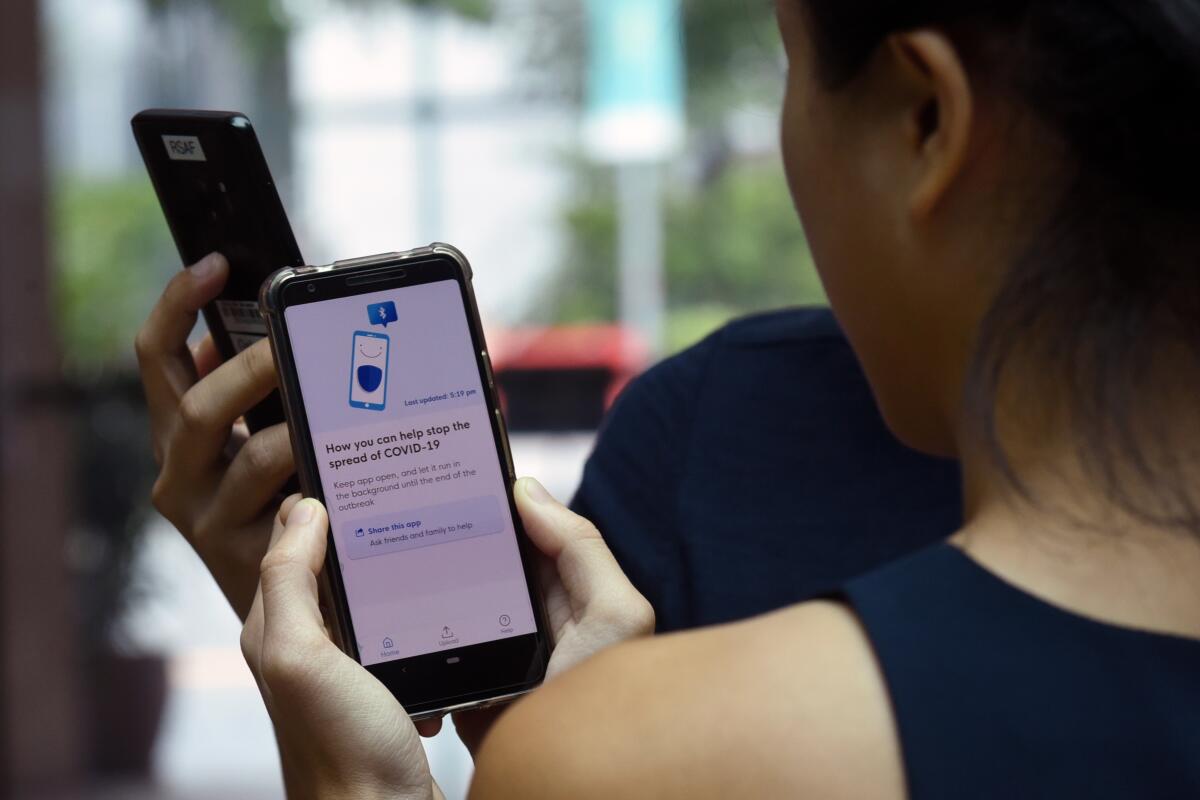

The TraceTogether program, which requires Singaporeans to download an app or carry a Bluetooth-enabled token, was introduced in March. Although participation is technically voluntary, officials have threatened social penalties for those who do not sign up. So far, more than 4.2 million people, or about three-quarters of residents, have joined the program.

The government had initially pledged that none of the data collected would be accessed unless an individual was found to have contracted the coronavirus and required contact tracing.

But in a session of Parliament on Monday, Minister of State for Home Affairs Desmond Tan said the data could also be used in criminal inquiries.

“Singapore Police Force is empowered under the criminal procedure code to obtain any data, and that includes the TraceTogether data for criminal investigations,” Tan said. “The government is the custodian of the [TraceTogether] data admitted by the individuals, and stringent measures are put in place to safeguard this personal data.”

TraceTogether’s app launch comes as concerns over privacy and intrusive surveillance are rising as governments try to curb the pandemic.

The TraceTogether website was updated later Monday to reflect the addition of criminal investigations to the potential uses of the program’s data.

The revelation comes after months of public reassurances that the app and token would not be intrusive and pleas for trust in adopting the program.

On Tuesday, Singapore’s foreign minister and head of its national technology initiative, Vivian Balakrishnan, told Parliament in an unscheduled statement that he had “not thought” to mention law-enforcement access to the program’s data, under Singapore’s Criminal Procedure Code, when he touted TraceTogether’s privacy features last year.

“Frankly, I had not thought of the CPC when I spoke earlier,” Balakrishnan said, adding that other sensitive data such as phone and banking records are also subject to criminal investigations. “I think Singaporeans can understand why the [CPC] confers such broad powers. There may be serious crimes — murder, terrorist incidents — where the use of TraceTogether data in police investigations may be necessary in the public interest.”

Governments worldwide are grappling with effective contact tracing, including the United States, where cooperation with the public has been undermined by misinformation and mistrust, and China, where contact tracing is suspected of enhancing the authoritarian government’s mass-surveillance tools.

The charges against activist Jolovan Wham reflect the zeal with which Singapore enforces its laws against protest.

Singapore, an island nation of 5.7 million, has whittled down the number of active cases to under 200 as of Monday after hundreds of people were being infected daily in cramped worker dormitories earlier in the pandemic. There have been a total of 29 deaths from the disease in the country, which has exhibited more signs of a return to normal life, such as in-person schooling and crowded restaurants and malls.

Singaporeans were initially skittish about TraceTogether, which uses Bluetooth to track users rather than GPS. An online petition calling for an end to the program over privacy concerns has attracted nearly 55,000 signatures.

Though voluntary, adoption of TraceTogether surged in recent months after the government announced that it would not loosen social restrictions until 70% of residents had downloaded the app or obtained a token. The government also said the app or token would be required to enter public venues later this year.

Tan said Monday that TraceTogether data needed for criminal investigations could be accessed only by “authorized officers” and that any misuse of the information could result in a $3,800 fine and/or up to two years in prison.

That did not prevent a backlash to the news. One tweet suggested Singaporeans toss their TraceTogether tokens in the trash.

Jolovan Wham, an activist who was arrested in November when he held up a smiley-face sign in public in a one-man protest, admonished the government on Twitter for going back on its word. He said he “sure as hell” would not download the TraceTogether app.

Any enhanced tools for authorities sets off alarms for rights advocates. Ruled by one party since independence in 1965, Singapore has little tolerance for criticism. It also has an abundance of laws that are enforced with the aid of closed-circuit cameras throughout the city.

“Singapore’s betrayal of its solemn promises to limit use of TraceTogether information to public health matters exposes how the government has been covertly exploiting the pandemic to deepen its surveillance and control over the population, and undermine the right to privacy,” Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director for Human Rights Watch, said in a statement.

“The government owes its people an apology for making false assurances and should protect the right to privacy by immediately firewalling the data collected from the app away from the police, prosecutors and other law enforcement personnel.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.