How an $8 part from Walmart makes it safe for choirs to sing again

MARQUETTE, Mich. — Baritone-for-hire David Newman was looking forward to a year of singing gigs.

Then, in March, the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, two members of a choir in Washington state died, and dozens more fell ill after their two-hour practice became a super-spreader event.

Concerts were quickly wiped from calendars around the world.

“The piercing irony of having to cancel is that the joy this music brings is what we now as a culture need more than ever,” said an email Newman received from Wisconsin’s Madison Bach Musicians.

Singing had been the centerpiece of his life. It got him through high school and into Westminster Choir College, a music school in New Jersey, where he majored in vocal performance.

When he wasn’t singing professionally, he taught voice as an adjunct professor at James Madison University near his home in Virginia.

Now singing could kill.

The choir world went into deep think. Some directors took to using software that allowed singers to record individual soundtracks to be layered into virtual concerts.

Newman, who is 52 and a commanding stage presence at 6 feet 3, believed computer tricks could never capture the magic of harmonizing in person.

Trying to sing together over the internet using programs such as FaceTime presented another problem: an audio delay known as latency that makes it impossible to sync up in real time.

“Every time I hear someone go, ‘Hey, is there an app that can let me do a choir rehearsal with no latency?’ I die a little on the inside,” one of Newman’s former students posted on Facebook. She wrote that she felt like telling people who bet that somebody would invent a solution: “NOT UNLESS YOU BREAK PHYSICS, YA DUMMY.”

From a makeshift office in his unfinished basement, Newman decided there must be a way for people to sing together remotely — and he set out to find it.

He typed his reply: “Physics are not insurmountable.”

::

Choir members often speak of how singing together stirs feelings far more powerful than singing alone.

“It is indescribable and awe-inspiring,” said Marlina Martínez, a 46-year-old amateur choir member in the northern Michigan town of Marquette. “It’s different every single time, because everyone brings their own emotions.”

Before the pandemic, 43 million adults and 11 million children in the U.S. belonged to choirs, according to the advocacy and research group Chorus America. Unlike church and bowling leagues, singing was seeing a rise in participation.

In 2016, Martínez was watching her son Oskar play bassoon in a concert with his high school band when a man in the audience noticed her singing along and complimented her voice.

Pete Stephens-Brown, a bus driver with a music degree, told her he conducted a choir and invited her to join.

Da Upper Yoopers’ Barbershop + Chorus — locals in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula call themselves Yoopers — sings in the “barbershop” a cappella style. The group once surprised a diesel mechanic working under a truck to deliver a song and a rose from his wife. When it sang at a courtroom naturalization ceremony, the federal judge couldn’t resist joining in.

The choir members quickly became family to Martínez, an East L.A. native who moved to Michigan two decades ago with her then-husband. The choristers appointed her president and sang to her mother in the hospital a week before she died of cancer.

Stories like hers abound — tales of people saved by singing.

“It can be an amazing way to reach kids from every background,” said Melanie Stapleton, 29, who runs a choir program for more than 250 students at Meyerland Performing & Visual Arts Middle School in Houston.

The deadly outbreak among members of a choir has stunned health officials, who have concluded that the virus was almost certainly transmitted through the air from one or more people without symptoms.

When Stapleton was growing up and trying to come to terms with being transgender, choir was the main place she found support.

On the side, Stapleton helped moderate a Facebook group of more than 27,000 choir directors, mostly fellow teachers who traded friendly tips on favorite choral numbers and ways to get kids to pay attention.

Once the news broke about the deaths of two Skagit Valley Chorale members in Washington, the conversation turned sharply to more existential matters.

::

Newman had always been something of an innovator.

He once turned his elder daughter’s third-grade science homework into a song about soil that took off on the internet.

Thinking about ways to keep people apart while allowing them to sing as one, he dug out an analog audio mixer and wireless microphones from his basement.

He reckoned it might work because it used radio waves, which travel at the speed of light, without being delayed by digital converters and routers.

He wished he could invite some friends over to help him experiment. He imagined them arriving in their cars. Then it hit him: cars. What perfect containment capsules, portable and readily available.

And so he decided to conduct a test.

On a Sunday afternoon in May, he stood in his driveway with the mixer and a speaker on the front lawn. Four friends pulled up in three cars.

His wife, Kira, handed out sanitized microphones and began shooting video. He chose a song that everyone would know and began conducting.

Sing we joyous, all together,

Fa la la la la, la la la la.

Heedless of the wind and weather,

Fa la la la la, la la la la.

The lyrics of the 16th century Welsh Christmas carol traveled from the mics to the mixer to the speaker.

The singers were able to do what had been denied them for months: sing together in real time.

Pleased, Newman posted the video on YouTube as “proof of concept.” The audio was crisp, he told his Facebook friends.

“For this rehearsal, nobody ever had to gather with anyone else indoors,” he wrote. “The type of equipment is well within the budget of most choral ensembles and already owned by most high schools and universities.”

Facebook friends were impressed, but a few noted flaws.

“Love this!! How do your neighbors feel?” one asked. “I’ll tell ya,” wrote another, “this is going nowhere in a Minnesota winter!”

Then Newman had another idea. He recalled the jalopy he drove in college, a 1967 Chrysler Newport. Because it lacked a cassette player, he had hooked an FM transmitter to his Sony Walkman to listen to tapes on the car radio.

Every car has a radio, he reasoned. An FM transmitter broadcasting from the mixer could let each singer hear the choir and harmonize in real time.

Newman tracked down the part at Walmart. It cost him $7.94 plus tax.

Hurrying home, he found a clear FM frequency — 90.3 — and set the transmitter to it. Then he plugged the device into the mixer.

He and his wife grabbed wireless microphones, hopped into their cars — Kira was parked down the street — and tuned their radios to 90.3.

Newman recorded the experiment for his next YouTube report: “Hello friends, I’ve got another video, and we’re testing out better technology. This is really exciting.”

“My wife is over here in that car — she’s going to flash her lights — there she is,” he explained. “And we’re just going to show you that ... there’s no perceptible latency between what you’re hearing in the car and what’s coming through the radio speakers, because everything’s happening at light speed.”

Kira chose another familiar song. “Row, row, row your boat, gently down the stream,” the couple sang in unison.

“Merrily, merrily, merrily, merrily, life is but a dream,” they continued in a round.

It was perfectly synchronized. Newman let loose a hearty laugh. “Oooh!” he said. “This is great.”

“I could definitely fit 40 cars within the range of this transmitter in a parking lot,” he told his audience.

::

Studies have found that choir members are more likely than the general population to vote, donate to charity and volunteer.

They have told researchers that choir singing gives them purpose and optimism, makes them more adaptable and less lonely and keeps them alert and healthy.

The residual benefits helped sustain many in the early days of the pandemic.

“Still missing my regular choir,” a singer from Illinois wrote on the Facebook forum Stapleton moderated. “But I’m fortunate to have a family who loves to sing.”

But it wasn’t long before the despair so much of society was experiencing reached the choir world. Evidence was mounting that the virus that causes COVID-19 spreads through the air, and scientists strongly warned against singing in groups.

Monitoring the Facebook comments, Stapleton sensed fear among teachers and professional singers and found herself playing referee as members fought over how much caution was necessary.

“I firmly believe that Covid is blown way out of proportion by the media,” wrote a teacher in Utah. “I will probably get chomped on for this comment, but oh well.”

A high school band director in Georgia proudly posted a photo of her band members in uniform, standing in distanced formation on a football field as spectators watched from the stands.

“Tonight we were able to have our fall concert and we didn’t have to sing with masks! It is possible!” she wrote.

A teacher in Houston jumped in. “I implore others not to do this,” he wrote. “I really hope none of your students were asymptomatic positive cases.”

Another wrote, “Beautiful sight!!!!”

Of 337 choruses surveyed in October by Chorus America, a quarter had stopped rehearsing or performing, and half had lost members.

The Upper Yoopers continued weekly meetings on Zoom, where singers could see one another, but only one person could be heard at a time.

“We’d go over a song we already knew, but it was difficult to do new stuff when we couldn’t hear each other,” Martínez said.

After a few sessions, Martínez couldn’t bring herself to participate.

All summer and fall, she ignored the rehearsal reminders and board meeting notices that stacked up in her inbox unopened.

One day, she and her son were walking along the shore of Lake Superior when he asked why she wasn’t singing with the group. He said it would be good for her.

She reminded him that she was the mother. But they both knew that she was dealing with deeper issues.

“For a person who’s never had depression, it’s hard to understand, but simple things become monumental tasks,” she said. “I’d rather try to climb Mt. Kilimanjaro than do the dishes.”

In early September, things got worse: She learned that her job would be eliminated.

She missed singing.

“The things that mean the most to us are the most dangerous,” she told her son.

::

Newman’s YouTube video was starting to attract attention.

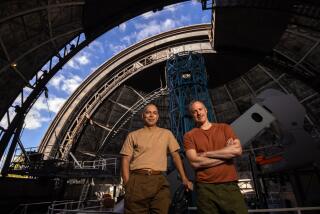

Among those who saw it was Kathryn Denney, a musical theater director and choir singer near Boston who had been conducting similar experiments with singers in cars.

She and her husband, Bryce, an electrical engineer, had beaten latency using gaming headsets. But their fix was not ideal. Each headset had to be plugged into a mixer — and it was hard to imagine managing all the cables that would be needed to connect large numbers of singers from their cars.

The moment they saw Newman’s video, the Denneys realized that his FM transmitter and wireless microphones offered a much more elegant solution. They decided to become its evangelists.

They created a “Driveway Choir” Facebook page and an instructional website. Then they took to the road, packing all the equipment they needed to help choirs throughout Greater Boston recapture live singing.

By mid-December, the Denneys had helped stage two dozen drive-in events involving hundreds of people and inspired others to spread the good news.

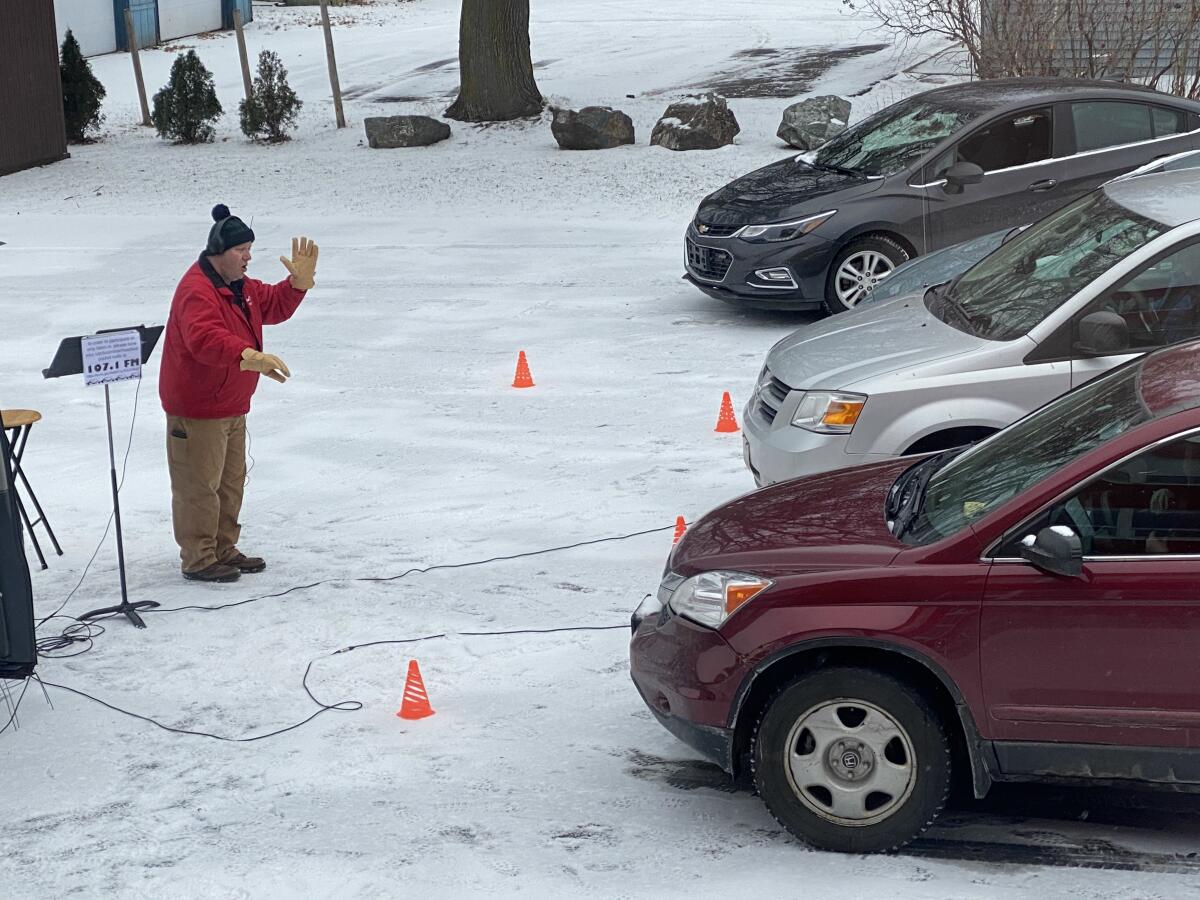

Word made its way to the Upper Yoopers.

Stephens-Brown raised donations and bought microphones, a headset and an FM transmitter. He borrowed a mixer from a co-worker.

After a few in-car practices, choir members had visions of performing again, but they wanted their president back.

In early December, one of the singers texted and called Martínez until she answered. Intrigued, she agreed to learn nine songs.

A few days later, she pulled her four-wheel drive Honda into a snowy church parking lot. Stephens-Brown guided the five vehicles into a semicircle so all the singers could see him through their windshields.

Martínez wished she could hug them all.

Everybody tuned their radios to 107.1 FM. Stephens-Brown listened through radio headphones over his ski hat as he conducted.

Snowflakes fell gently as the singers launched into “Silent Night.”

They sang on: “Away in a Manger,” “O Holy Night,” “Coventry Carol.”

As her own voice in harmony with the others filled her car, Martínez began to tear up.

She had missed her friends.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.