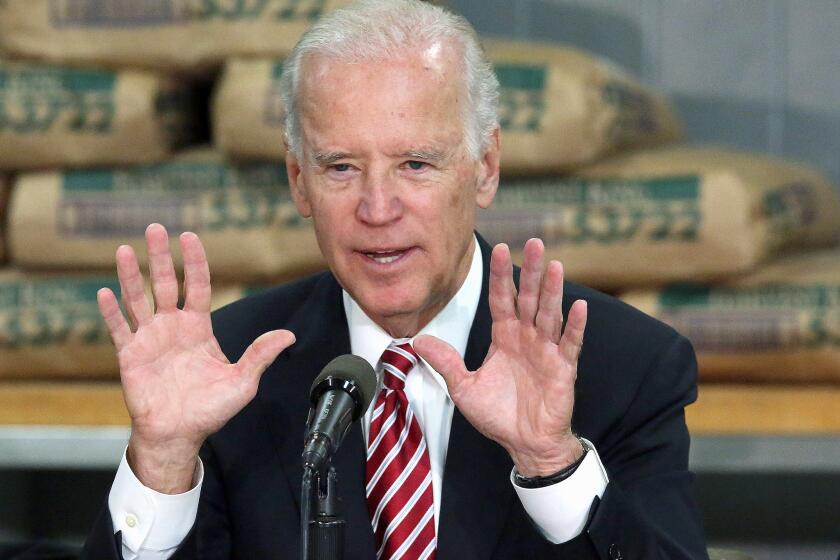

European allies’ relief over Biden’s presidential win tempered by underlying tensions

BERLIN — Following a rush of thinly concealed relief over President Trump’s failure to win reelection, major European allies of the United States are putting aside euphoria and coming to terms with some hard realities about the relationship going forward.

Analysts say transatlantic ties under the incoming president, Joe Biden, are likely to be far more calm, cordial and conventional than during the Trump years, when the U.S. president made clear his disdain for bedrock postwar institutions such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, which he once called obsolete, and the European Union, which Trump declared was “worse than China.”

In a Biden era, European leaders are unlikely to be blindsided by bizarre contretemps such as Trump’s abrupt expression of interest last year in buying Greenland, and his angry reaction when Denmark informed him that the semiautonomous island territory within its kingdom wasn’t for sale.

Some U.S.-European tensions predate Trump’s turbulent turn on the world stage, and others are likely to come urgently to the fore in the early days of the Biden administration, including Europe’s differences with the U.S. over China policy.

But while the president’s combative style served to highlight divergent interests on either side of the Atlantic, the end of his term in office will not mark a simple reset, analysts and commentators said.

“The biggest mistake would be to settle for that sigh of relief,” France’s most prestigious newspaper, Le Monde, warned in an editorial this week. Biden, it said, would be handed “the immense task of rebuilding everything, or almost everything.”

Biden has already announced plans to immediately rejoin the Paris climate accord upon taking office Jan. 20, and to reverse Trump’s mid-pandemic abandonment of the World Health Organization.

But European leaders have been coming to terms with the United States not being as powerful or as reliable an ally as it was four years ago, when Biden was wrapping up his tenure as vice president under President Obama. Nor do they believe, based on U.S. election results, that Trump’s brand of hard-line isolationism and protectionism has gone away for good.

“The issues such as ‘America first’ that Donald Trump talked about so successfully in his campaign four years ago, and just now, are not going to disappear,” said Juergen Hardt, a senior German lawmaker and the foreign policy point person for Chancellor Angela Merkel’s conservative party.

Alluding to the outgoing president’s refrain that Europe was taking advantage of the United States on matters including trade and defense spending, Hardt said Trump “was able to profit from those sentiments … We’ve got to do a better job clearing up those misunderstandings.”

How will Joe Biden handle the sensitive relationship between superpower rivals China and the U.S.?

Many European officials believe a second Trump term could have spelled doom for NATO, the now 30-member alliance that was created more than seven decades ago to provide collective security against the Soviet Union.

A Biden presidency staves off that existential threat, and the new U.S. president is unlikely to publicly excoriate leaders such as Merkel over the amount they spend on national defense, as Trump routinely did.

But many analysts say the burden-sharing does need recalibrating, and Biden — who called for NATO reforms in a speech last year to the Munich Security Conference — is likely to press that message, though in a more conciliatory manner.

The incoming administration “needs to keep telling Europeans: You want U.S. troops to protect you in Europe? Then spend at least 2% GDP you promised on YOUR OWN defense,” Jakub Janda, director of the European Values Center for Security Policy, wrote on Twitter. “U.S. taxpayers are not going to subsidize you.”

For centrist European politicians, Trump’s ascendancy four years ago was all the more alarming in the context of a populist wave then sweeping across the continent, and Britain’s approval of the 2016 Brexit referendum came just five months before Trump’s unexpected victory.

Far-right and nationalist parties still dominate governments in EU member states including Poland and Hungary, neither of whose leaders had extended congratulations to Biden as of Thursday. Biden became president-elect based on vote counts a few days after the Nov. 3 election, though Trump has not conceded.

Populist firebrand Marine Le Pen of France’s National Rally, asked by reporters Wednesday if she recognized Biden’s victory, which is now mathematically clear, retorted: “Absolutely not.”

Populist sentiment is already coming into play in both the United States and Europe as coronavirus caseloads surge to record highs. And the two share a troubling trend: Resistance to restrictions to stem the spread of the virus has become a right-wing rallying cry.

Even with heightened hopes for a safe and widely available vaccine — the pharmaceutical company Pfizer this week announced successful clinical trials — Biden and his European counterparts will face the prospect of devastating death tolls during the winter, together with deepening economic hardship that could galvanize anti-government sentiment.

For now, though, the Biden transition has featured steps seemingly meant to symbolize a return to traditional tenets of U.S. foreign policy. The president-elect’s first round of calls with foreign leaders this week emphasized long-standing European alliances; he spoke Tuesday with Merkel, French President Emmanuel Macron, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Prime Minister Micheal Martin of Ireland.

Even if cheered by swift contact with Biden, though, European leaders generally expect that he will pick up where the Obama administration left off, moving ahead with a strategic U.S. pivot to Asia.

“We Europeans shouldn’t live under any illusions: Joe Biden will continue the focusing on the Asia-Pacific region that was starting under President Barack Obama,” Germany’s vice chancellor and finance minister, Olaf Scholz, wrote in a commentary in the magazine Der Spiegel.

And relationships with old allies may soon involve new complications. Johnson was so ebullient about his conversation with Biden that, when speaking to lawmakers Wednesday, he prematurely referred to Trump as the “previous president.”

Johnson’s political foes said his close ties with Trump, a fellow booster of Brexit, could come back to haunt him. Biden, who often alludes fondly to his Irish heritage, has made it clear that any post-Brexit arrangement must not endanger the still-fragile peace between Northern Ireland, which is leaving the EU along with the rest of the United Kingdom, and the Republic of Ireland, which is remaining in the bloc.

Biden’s transition office said that in Tuesday’s talks he “reaffirmed his support for the Good Friday Agreement,” which essentially did away with the border between the island’s north and south. Johnson’s government has failed to convince critics that Brexit can go forward without the prospect of reimposed border checks at the Irish frontier, which will be Britain’s new external border with the EU, likely imperiling the accord.

Many European leaders, including Germany’s president, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, saw a stepping back from the brink in Biden’s election. Writing in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, one of Germany’s leading newspapers, Steinmeier pushed back against those who believe little will change in U.S. foreign policy toward Europe and others.

“These skeptics are missing the point,” he wrote. “The return to these shared ideals by the U.S. is an opportunity to end the erosion of the international order.”

Special correspondent Kirschbaum reported from Berlin and Times staff writer King from Washington.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.