Around Nagorno-Karabakh, an all-out media war unfolds

BAKU, Azerbaijan — In a warehouse on the outskirts of this city, famed singer-songwriter Tunzala Aghayeva stood on a dais and adjusted the beret she wore atop a fitted, black-and-white camouflage coat and gray jumpsuit. Before her, an octet of burly men in matching fatigues and beige do-rags danced with gusto to orchestral strains and a martial drumbeat.

“Motherland, we are together,” Aghayeva sang in a husky alto, as a camera operator panned across a plume of fire and a smoke machine. “Bright victory is with us, glorious motherland and soldier of Azerbaijan.”

During a break from filming the music video, Aghayeva said that the “best type of music is the one which calls for peace and friendship.” But this new release was to be a full-throated motivational ode to the Azerbaijani soldier, another broadside in the all-consuming media and information war that has flared with the same ferocity as the armed fight happening more than 170 miles away in the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Since late September, the Azerbaijani army has been on an offensive to recapture the ethnic Armenian enclave, which is recognized as part of Azerbaijan but which the country was forced to relinquish along with other territories after losing to Armenia in a 1994 war. A Russian-brokered truce signed Tuesday has — so far — ended the skirmishes, but not before more than 1,000 soldiers and civilians have been killed and hundreds of thousands of residents displaced.

The cease-fire’s terms are a victory for Azerbaijan, which has retaken significant pockets of territory, including Shusha, Nagorno-Karabakh’s second-largest city (Armenians call it Shushi). Thousands of Armenians furious at their government’s acquiescence to the truce protested in Armenia’s capital, Yerevan, many of them shouting: “We won’t give up our land!”

The fiery nationalist passions in Armenia and Azerbaijan are both a prod to and a product of the two sides’ unrelenting propaganda war.

At the entrance to the Tashir shopping gallery in the heart of Yerevan, video screens play state-media broadcasts on a continuous loop, while billboards display pictures of soldiers in scenes of battle. Similar images abound here in Baku, the Azerbaijani capital, with the hashtag “Karabakh is Azerbaijan” peppered throughout the city.

Their decades-old battle over the mountainous territory of Nagorno-Karabakh has come to define how Armenians and Azerbaijanis view themselves.

In places as distant as Los Angeles and Beirut, both home to significant Armenian diasporas, pro-Armenian activists have marched, gathered assistance and organized volunteers for the defense of the separatist government in Nagorno-Karabakh, which Armenians call Artsakh.

Both Armenia and Azerbaijan have marshaled musicians, Twitter and Facebook partisans, officials and lobbyists to trumpet their cause and paint the other side as subhuman killers. The vitriol is likely to complicate plans for a long-lasting reconciliation between two peoples now facing the prospect of living side by side in Nagorno-Karabakh once more.

In recent weeks, both sides have released a raft of songs and video clips similar to the one Aghayeva was recording. In “Ates” (“Fire”), a heavy-metal production by Azerbaijan’s state border service, singers in fatigues perform before a tableau of soldiers and weapons, saying that “Karabakh is in trouble and calls us for revenge” and that the country’s lands “will be liberated and bonfires will light” the borders.

A sort of response came from System of a Down, an Armenian American metal band from Glendale, whose members reunited for the first time in 15 years to release the songs “Protect the Land” and “Genocidal Humanoidz.” The latter echoes widespread fears among the Armenian diaspora of the Turkish-backed Azerbaijani army committing genocide against Nagorno-Karabakh’s majority-Armenian population.

“These two songs ... both speak of a dire and serious war being perpetrated upon our cultural homelands of Artsakh and Armenia,” a statement from the group said, adding that royalties would be donated to a U.S. charity that provides “those in need in Artsakh and Armenia with supplies needed for their basic survival.”

On social media, officials from both countries snipe at each other’s posts, disputing every military advance or retreat and leveling charges of war crimes. Their respective defense ministries post gruesome footage on YouTube — complete with Wagnerian soundtracks — boasting of battlefield achievements. Supporters, backed by bot accounts, harass each other or throw accusations of fake news, often tweeting under rival hashtags such as #EndArmenianOccupation and #SaveArtsakh.

In October, Facebook removed 589 accounts and 7,665 pages on its platform as well as 437 accounts on Instagram that it said were “involved in coordinated inauthentic behavior” originating in Azerbaijan, whose purpose was “to comment and artificially boost the popularity of particular pro-government content.”

International celebrities have gotten involved, too. Kim Kardashian has turned her social media presence into a pulpit for the Armenian side, as has Alexis Ohanian Sr., the founder of Reddit. Oscar-winning actress Penelope Cruz inadvertently got caught up in the fight after posting a promotional picture of herself with the Colombian flag as a background. That was mistaken for a gesture of solidarity with Armenia, whose flag has similar colors; it kicked up a furious flood of comments from Azerbaijanis and Armenians.

Meanwhile, lobbyists have worked on overdrive to build support, especially in the U.S. Using its oil riches, Azerbaijan pays hundreds of thousands of dollars each month to Washington-based influence-peddling outfits such as the Podesta Group and BGR Group.

Armenia has its own lobbying arm, the Armenian National Committee of America, which has for years succeeded in getting the U.S. government to pay between $5 million and $10 million a year in financial aid to the so-called Republic of Artsakh, despite the fact that Washington does not officially recognize the breakaway government.

The use of drones has upset the military balance between Azerbaijan and Armenia in their longtime dispute over the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Over the weekend, as the Azerbaijani army bore down on Shusha, the media war intensified, hardening the already-entrenched attitudes of those advocating for a fight to the finish.

Videos and comments from the official account of Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev purported to show that Baku had reasserted control over the strategic city, which lies on a mountain and is seen as the gateway to controlling Stepanakert, the enclave’s capital.

Despite reports that the Azerbaijani army had encircled the enclave, the Armenian side initially denied any setback, with officials insisting that everything was under control.

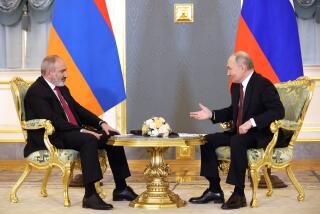

But soon that insistence faltered. By early morning Tuesday, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan declared on Facebook that he had signed the Russian-brokered agreement stopping hostilities. It was, he said, an “unspeakably painful” decision but he felt it offered “the best possible solution.”

The agreement calls for Armenia to give back the seven provinces around Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijan, for the withdrawal of Armenian forces and for the return of some 800,000 people displaced from the enclave and adjacent territories. About 2,000 Russian troops would be deployed as a peacekeeping contingent for five years, and would guarantee passage between Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia at the Lachin corridor, a vital choke point.`

Here in Baku, Aliyev characterized the agreement as “Armenia’s capitulation” and a “Glorious Victory.”

For his part, Pashinyan tried hard to put a positive spin on what had happened.

“This is not a victory, but there is no defeat as long as you do not think of yourself as defeated,” he said in a Facebook post that received more than 55,000 comments, most of them furious. Twenty minutes after it came out, protesters stormed Armenia’s parliament and demanded his resignation.

Official acknowledgment that disaster was imminent had come a day earlier, when Vahram Poghosyan, spokesman for Nagorno-Karabakh’s presidency, admitted on Facebook that Shusha “is completely out of our control” and that the “existence of the capital city [is] threatened.”

Suddenly, the limits of an all-out media war were painfully apparent.

“All kinds of encouraging or inspiring propaganda do not give us anything,” Poghosyan said, “besides losing the sense of reality.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.