BEIJING — The oil company worker wondered why he had to keep his vaccination a secret. Questions raced through his head as he read the confidentiality agreement, which threatened discipline if he told anyone outside company management about the COVID-19 shot he was waiting to get.

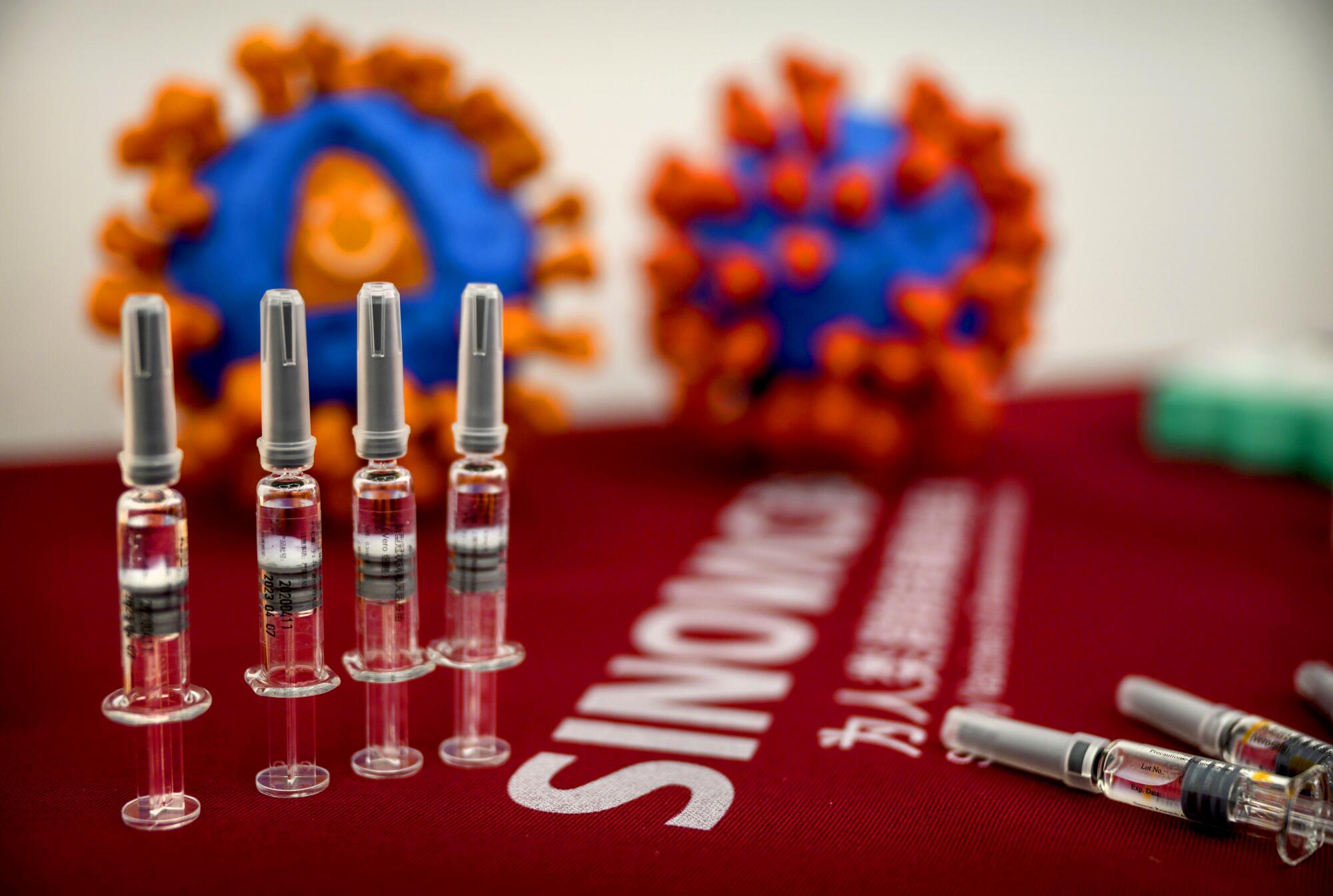

What if something went wrong? Who would take responsibility? The worker knew the vaccine maker, China National Biotec Group — part of the state-owned pharmaceutical group Sinopharm — was conducting trials of this vaccine on hundreds of thousands of volunteers in the United Arab Emirates, Peru, Morocco and other countries.

“At least they’re in a monitored, controlled situation,” he said of those trials, watching as hundreds of his co-workers lined up around him to get their injection at a clinic in Beijing. “But for us, they can’t make any guarantees. This is us making a sacrifice for the nation.”

The employee — who did not give his name for fear of reprisal — is one of hundreds of thousands of Chinese citizens who have received COVID-19 vaccines before they have been proved safe in clinical trials. China’s military began getting vaccinations in June. Medical workers and employees of state-owned companies working abroad were soon included in an “emergency use” program. In September, a China National Biotec executive said 350,000 people outside clinical trials had already received the vaccine.

Early vaccinations of high-profile people have become a way to show trust in China’s medical system after a 2018 scandal in which children were exposed to faulty vaccines for diphtheria and tetanus.

In March, images of Chen Wei, a military general and epidemiologist leading one of the coronavirus vaccine efforts, were widely shared by social media users, praising her for receiving an injection before it had been tested on animals. Yin Weidong, chief executive of biopharmaceutical company Sinovac, told reporters last month that he was one of the first to take the vaccine after it passed the first two trial phases. About 90% of Sinovac’s employees have voluntarily taken the vaccine early, the company said.

This month, China National Biotec Group reportedly began offering free vaccines to Chinese students planning to go abroad, according to a company website that was later taken down. More than 93,000 people had signed up for the free vaccine, the website said. Students who had been vaccinated also spoke to local and foreign media about their experiences. But state media later reported that the free vaccine offer was “not real.”

Several cities in Zhejiang province have also reportedly begun offering vaccines made by Sinovac. In Yiwu city, Chinese media found a clinic offering vaccination shots for about $30 each on a “first come, first served” basis. Most of those receiving shots were people planning international travel, though they did not have to prove it, according to local reports.

None of the vaccines have completed Phase 3 trials, which often catch rare side effects that go undetected in earlier phases.

Chinese health authorities have said that the vaccines are safe, with no severe adverse effects, and that their “emergency use” is justified to protect against imported infections or a domestic resurgence of COVID-19. But health experts outside China are questioning the safety and ethics of such a strategy, especially when China has largely contained the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It’s a huge gamble, because you’re giving the vaccine to people who are healthy,” said Lawrence Gostin, director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University.

Such a risk might make sense in a country where the virus was rapidly spreading and front-line workers were constantly exposed to COVID-19 — as in the United States — but Western health experts and vaccine makers have been wary of prematurely rolling out a vaccine.

“I would not expect a country with a highly developed regulatory and safety system like the United States, the European Union [states] or Japan to allow that kind of wide access to an unproven vaccine,” Gostin said. “It’s unethical, and it’s dangerous.”

The oil company worker, who is usually based in a Persian Gulf country but has been stuck in Beijing since January, sent copies to The Times of the consent forms and confidentiality agreement he had to sign before receiving the vaccine. He also provided screenshots of WeChat discussions about vaccinations among his colleagues.

The worker said he received the vaccine in September as a requirement for all staff working abroad. He worried about the lack of transparency or scrutiny in China’s mass vaccination of state-owned company employees and other citizens. There was no written document forcing them to receive the vaccine, he said, but workers were not being cleared to return to their jobs abroad unless they were vaccinated.

“Are you afraid of the vaccine? Of course. But are you afraid of getting the sickness? Yes, you’re always afraid,” the oil company worker said.

It was “politically incorrect” to question the vaccine at his company, he said. Most of his colleagues were eager to get it. They were more afraid of catching COVID-19 abroad than of safety concerns with the vaccine.

Some project managers were rushing the vaccinations, he said, by encouraging employees to receive two shots at once instead of waiting the recommended 14 or 28 days between injections.

“I saw that some people got two shots together.… But you have to say you’re urgently departing the country,” a colleague who appeared to be coordinating staff vaccinations wrote in one of the WeChat screenshots. “I’m thinking the three of you can save a trip and get back to the project earlier.… Ask them if you can get both shots at once,” the colleague said.

A consent form shared by the employee appears to verify this account: “If you urgently need to go abroad and truly cannot complete the two-shot vaccination, you can consider receiving two injections at once, one each on the left and the right,” the form says.

Although severe adverse effects had not been observed in this vaccine, the form warns of possible fever, fatigue, diarrhea and headaches. Other vaccines on the market sometimes caused severe reactions such as anaphylactic shock. If that happened to a vaccination subject, the person should “seek timely treatment,” the form says.

Vaccine doses are usually spaced out so that the first “priming” dose sensitizes a body’s immune system to recognize a new pathogen, while the second “booster” dose stimulates higher antibody levels, said Keiji Fukuda, director of the University of Hong Kong’s School of Public Health and a former World Health Organization official.

Giving two doses on the same day is an attempt to drive antibody levels higher by giving more vaccine, he said: “The prime-boost approach takes advantage of how the immune system works naturally. The large dose approach is more like applying brute force.”

Premature vaccine use can also create a false sense of safety, said Yanzhong Huang, a senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations. China calls its emergency use vaccines effective because they produce antibodies, he said: “But that is a low threshold.”

More testing is needed to show how effective the antibodies are, how long they last, and whether they can protect against different strains of the coronavirus — questions that cannot be answered in China, where the lack of an active outbreak makes it hard to prove whether a vaccine is working.

A representative of the oil company said over the phone that he “could not disclose any information” regarding vaccinations. Sinopharm did not pick up phone calls or respond to faxed requests for comment.

A Times reporter visited the site where the oil company worker was vaccinated, a clinic near Beijing’s Olympic Park, in late September. Medical staff there confirmed that they were giving out coronavirus vaccines, but only to employees of designated state-owned enterprises, and said all their appointment slots for the coming month had been filled.

Sinovac, the company whose vaccines are reportedly being distributed in Zhejiang, did not pick up phone calls or respond to emailed requests for comment.

The opacity of China’s vaccine experiments has sparked backlash. Papua New Guinea complained in August when China sent mine workers who’d received vaccines to the South Pacific country without fully disclosing whether they were part of a trial or the risks involved in receiving vaccinated workers.

But many countries are also clamoring for China’s coronavirus vaccines, which Chinese President Xi Jinping has pledged to make a “global public good.” Brazil’s health regulator approved the import of 6 million vaccines from Sinovac this week. The United Arab Emirates approved its own emergency use of a Sinopharm vaccine in September. Sinovac has agreed to supply 40 million doses of its vaccine to Indonesia by March.

China announced this month that it was joining COVAX, a global initiative to ensure equitable distribution of vaccines to developing countries. Sinopharm also announced this month that it was preparing production lines in Beijing and Wuhan to make 1 billion doses of its vaccines next year.

Such moves have bolstered China’s soft power regardless of questions about vaccine transparency, especially in comparison with the United States, which has struggled to contain its COVID-19 outbreak, withdrawn from the WHO and refused to participate in COVAX.

“We cannot claim that moral high ground when we accuse China of using the vaccine to achieve their foreign policy goals. No matter what they are doing, at least they benefit people in the developing world,” Huang said. “We like to talk about China exercising vaccine diplomacy, but the U.S. is not even part of the game.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.