If you die before election day, does your early ballot count? That depends

ATLANTA — At 90 years old and living through a raging pandemic, Hannah Carson knows time may be short. She wasted no time returning her absentee ballot for this year’s election.

As soon as it arrived at her senior-living community, she filled it out and sent it back to her local election office in Charlotte, N.C. If something were to happen and she doesn’t make it to election day, Carson said she hopes her ballot will remain valid.

“I should think I should count, given all the years I have been here,” she said.

But it might not. In North Carolina, an early ballot cast by someone who subsequently dies can be set aside if a challenge is filed with the county board of elections before election day.

Questions over whether such ballots will count are especially pressing this year amid a pandemic that has been especially dangerous for older Americans. People 85 years and up represent nearly 1 in 3 deaths from COVID-19 in the U.S. As an election looms, the odds against older people who become infected with the coronavirus are on the minds of older voters and their family members.

Seventeen states prohibit counting ballots cast by someone who subsequently dies before election day, but 10 states specifically allow it. The law is silent in the rest of the country, according to research by the National Conference of State Legislatures.

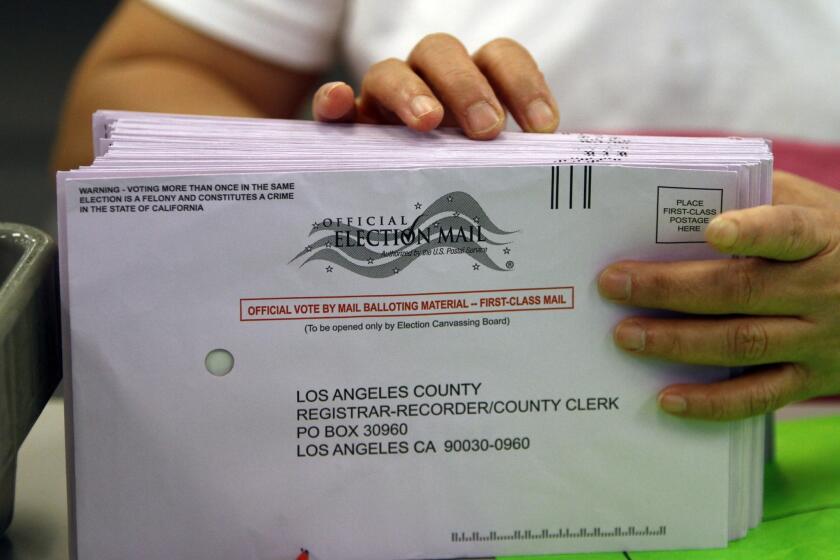

With election day over two weeks away, more than 1 million Californians have returned mail-in ballots, dwarfing the number submitted at this point in 2016.

In California, it’s an issue of fairness to count ballots cast by people who then die before election day, Secretary of State Alex Padilla said. He said it’s just as conceivable that someone who votes early in person also dies before election day, and there is no way to identify and reject that ballot.

“The dead voters [issue] is used as a false narrative, a pretext for changes in some states to how they register voters or count ballots when the data shows otherwise,” Padilla said.

Even where a law requires such ballots to be rejected, it’s likely that some could still count depending on when the person dies and when election officials find out about the death.

“The law may say that the ballot of a person who dies in that situation can’t be counted, but it is a hard law to follow,” said Wendy Underhill, head of elections for the National Conference of State Legislatures.

With early voting underway, Texas Republican leaders are waging a legal battle against voter rights groups.

When someone dies close to an election, it takes time for death records to be updated, and there is a narrow window between when a ballot is cast and counted. Colorado in 2016 had between 15 and 20 instances of voters who cast a ballot by mail and then died before election day. All were counted.

In Michigan’s primary earlier this year, 864 ballots were rejected because the voters died before the election even though they were alive when they filled them out.

Donald Trump Jr. tweeted a link to a story about the dead voters in Michigan that was later debunked for misrepresenting the issue. With his father, President Trump, making unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud, the question of whether ballots count if early voters die soon after casting them could fuel more conspiracy theories.

Studies have shown that voter fraud is exceptionally rare. There are numerous safeguards built into the system to ensure that only people eligible to vote can do so and that they cast only one ballot. Election officials say that when fraud does happen, people are caught and prosecuted.

Early voting rush: Nearly 10 million Americans have already voted in the presidential election. Around the same time before election day in 2016, 1.4 million had.

“There have been umpteen examples of some group claiming a whole bunch of people casting ballots after they died,” said Justin Levitt, an election law expert who has studied voter fraud in depth. “These things don’t pan out.”

In most cases, claims of dead voters are based on poor information or a faulty analysis that fails to account for the many people who share the same name and birthdate, Levitt said.

In an exceptionally small number of cases, there is fraud. Levitt said this typically involves someone wanting to honor the wishes of a loved one who recently died and, either knowingly or not, commits a crime by filling out the deceased person’s ballot.

An election judge from southern Illinois was charged in 2016 with voter fraud after she filled out a ballot for her late husband because she said he would have wanted Trump to be president.

Show off your early voting pride with our “I voted early” stickers on Instagram and in print.

Wisconsin, which like North Carolina is a presidential battleground this year, is among the states that prohibit a ballot from being counted if the voter dies after submitting it. Every month, the state’s election commission receives records of county death certificates, and those records are run against the statewide voter registration system.

Any potential matches are flagged to the local clerk where the voter is registered, and the clerk is responsible for verifying the match by looking at obituaries and other sources before changing the voter’s status, said Reid Magney, Wisconsin Election Commission spokesman.

But that also has its limits.

“There’s no way to check every absentee ballot to make sure the voter hasn’t died since it was issued,” Magney said.

Iowa’s election office receives death records and processes them as they are received, including on election day. If a person dies after requesting or returning an absentee ballot, the ballot is voided and not counted, said Kevin Hall, spokesman for Iowa’s secretary of state.

“Voters have to be eligible electors on election day,” Hall said. “Even though Iowa had 29 days of absentee voting, there is still only one election day.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.