Toots Hibbert, beloved reggae star, dies at 77

Toots Hibbert, the charismatic reggae singer and bandleader who helped transform the groove-driven sound of 1960s Jamaica into an international musical movement, has died. He was 77.

Hibbert, frontman of Toots & the Maytals, had been in a medically induced coma at a hospital in Kingston, Jamaica, since earlier this month. He was admitted in intensive care after complaints of having breathing difficulties, according to his publicist. It was revealed in local media that the singer was awaiting results from a COVID-19 test after showing symptoms.

News of the five-time Grammy nominee’s ill health came just weeks after his last known performance, on a national live-stream during Jamaica’s Emancipation and Independence celebrations in August.

A family statement said Hibbert died Friday at University Hospital of the West Indies in Kingston, surrounded by family, the Associated Press reported.

One of the titans of Jamaican ska and reggae music, Hibbert and his vocal trio the Maytals helped set the template for the genres starting in the early 1960s with hits including “Bam Bam,” “54-46 That’s My Number” and “Monkey Man.” His 1968 song “Do the Reggay” helped popularized the term “reggae.”

But it is Hibbert’s exuberant five-word refrain to open the Maytals’ biggest hit, “Pressure Drop,” that will forever be his calling card:

“It is you — oh, yeah!”

The soaring, gospel-informed song earned him and his band worldwide success after it was included on the soundtrack to the 1972 Jamaican crime film “The Harder They Come.” Alongside now-classics of the genre including Jimmy Cliff’s title track, the Slickers’ “Johnny Too Bad” and the Melodians’ “Rivers of Babylon,” “Pressure Drop” as sung by Hibbert resonated like a wail from the heart of Kingston.

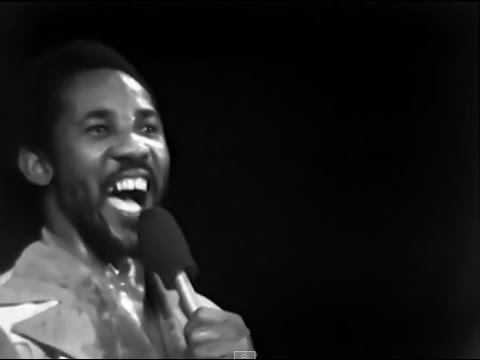

Toots Hibbert of Toots and the Maytals sings his hit “Pressure Drop” in 1975.

By then Hibbert had renamed the group to give himself top billing, and as Toots and the Maytals he relentlessly toured the world: In Nigeria, he toured with Fela Kuti. In England, he inspired the punks. In America, he shared bills with platinum artists including the Eagles and the Who. At Anaheim Stadium in 1975, Hibbert and his band opened for Linda Ronstadt, then at the peak of her commercial success.

Along the way, “Pressure Drop” became an anthem that crossed oceans and borders. Its message of karmic justice earned further attention when the punk band the Clash released a version of it in 1978.

Against a backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic, ongoing racial unrest and an upcoming election, Grammy season kicks off in earnest this week.

Born on land originally settled by British colonists as a plantation, Frederick Nathaniel Hibbert named the vocal trio he founded with Ralphus “Raleigh” Gordon and Nathaniel “Jerry” Matthias after his home district of May Pen. Hibbert had met them shortly after moving 35 miles east to the Trenchtown neighborhood of Kingston as a young teen. Then the city’s cultural center, it was dense with record shops and clubs.

There the three connected with early recording studio entrepreneur Clement “Coxsone” Dodd, who had an at-the-ready studio band called the Skatalites to back vocalists on recordings. Not yet a hot commodity, Dodd’s label Studio One issued a series of bouncy Maytals ska singles, dense with brass and that archetypal offbeat rhythm, that were hits in Kingston.

“My influences when I was coming up in the business were Ray Charles, Sam Cooke, Jackie Wilson and Otis Redding,” Hibbert told The Times in 1989. “I’d heard them on the radio in Jamaica and fell in love with the voices in the songs. I started to sing and people would tell me I would sound like Ray Charles or Otis Redding, so I figured these guys are my brothers.”

Hibbert was one of a posse of young Kingston crooners and bandleaders working the party circuit at the time. Alongside kindred spirits including the Wailers (Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer), saxophonist Tommy McCook and singer Jimmy Cliff, Hibbert and the Maytals starting in 1964 banged out songs at a fast clip, many in single takes. He had a knack for catchy singalong choruses.

The Maytals’ 1966 hit “Bam Bam” helped codify a phrase that has since become part of the DNA of reggae and dancehall. Another local smash, “54-46 That’s My Number” (1968), recounted in song the 18 months Hibbert spent in jail after being arrested for marijuana possession.

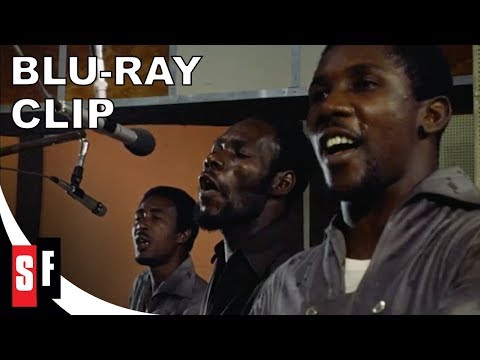

Toots Hibbert and the Maytals perform in a scene from “The Harder They Come”

At the start, ska, rocksteady and early reggae were mostly local phenomena. Much of Western youth culture was focused on the British Invasion in 1964, but beneath the screams of Beatlemaniacs was a bass-focused rumble emanating from Jamaican dance floors. It jumped to Jamaican communities in London, where British record man Chris Blackwell fell in love with the music and realized its commercial potential outside of the Caribbean islands. After establishing Island Records and releasing the soundtrack to “The Harder They Come,” Blackwell signed Hibbert.

His urgent, joyous 1973 album “Funky Kingston” led the way. The work captured the Maytals in full reggae-funk mode, mixing Kingston rhythms with expansive, Kuti- and James Brown-inspired proto-disco. In addition to the title track and “Pressure Drop,” the album saw Hibbert exploring crossover material, including a version of John Denver’s “Country Road” and Richard Berry’s “Louie Louie.” Regardless of genre, Hibbert’s raspy, soaring baritone could lift to a tenor, then to falsetto and swan dive back down, all across the course of a few choice lines.

Hibbert issued more than two dozen studio albums across his career, along the way collaborating with artists including Steve Winwood, Bonnie Raitt and Derek Trucks. He dabbled with American R&B on “Just Like That” in 1980, but as the electronically charged subgenre dancehall supplanted reggae on the Kingston charts, Hibbert took a pause. “After the deaths of ... Bob Marley and Peter Tosh, I figured I should eat other seeds,” Hibbert told The Times. “I stopped singing for a long while, and was just writing songs and teaching the youths.”

Devo cofounder Mark Mothersbaugh spent weeks in Cedars-Sinai hospital, hooked up to a ventilator, his mind wracked by violent hallucinations.

As he was on hiatus, a multicultural mix of working-class kids in England were rediscovering ska. One of the most popular acts to spring out of the scene, the Specials, recorded Hibbert’s “Monkey Man,” and in doing so turned it into one of the first ska-punk anthems.

Hibbert’s 1988 return, “Toots in Memphis,” was also a grand departure. Rather than on the island, he traveled to onetime Rolling Stones keyboardist Jim Dickinson’s Memphis, Tenn., studio. For the session, Dickinson rounded up members of Stax Records’ roster, including the Memphis Horns, to create a seamless blend of reggae, soul and R&B that underscored the spiritual kinship.

Across his career, Hibbert toured the world as a reggae ambassador, most notably during his many appearances at the long-running Reggae Sunsplash series of annual festivals. By the ‘00s, those concerts and his records had drawn a host of admirers, some of them featured on his 2004 album “True Love.” Featuring collaborations with Willie Nelson, the Roots, Keith Richards, Manu Chao, No Doubt, Trey Anastasio and others, the album confirmed Hibbert’s universal appeal. It also earned him his only Grammy Award.

Hibbert remained active until very recently and remained a beloved figure at home. In 2012, he was conferred the Order of Jamaica, a cultural honor awarded to Jamaican citizens of outstanding distinction. “I’m not surprised people still remember him. He’s a very nice person,” Hibbert’s wife of more than 50 years, Doreen, told the Jamaican Gleaner at the time.

In late August, he released his final studio album, “Got to Be Tough,” featuring contributions from drummer Sly Dunbar and percussionist Cyril Neville. A buoyant album that features a cameo by Ziggy Marley, it was produced by Hibbert himself.

The highlight is the title track. Featuring a typically bass-heavy rhythm and synthesizer chords, the Hibbert-penned song teems with an urgent warning made for these times: “Got to be tough when things get rough / You got to be tough and this is a warning / You got to be smart, living in this time / It’s not so easy to carry on.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.