Israelis turn to familiar institution to fight coronavirus: The army

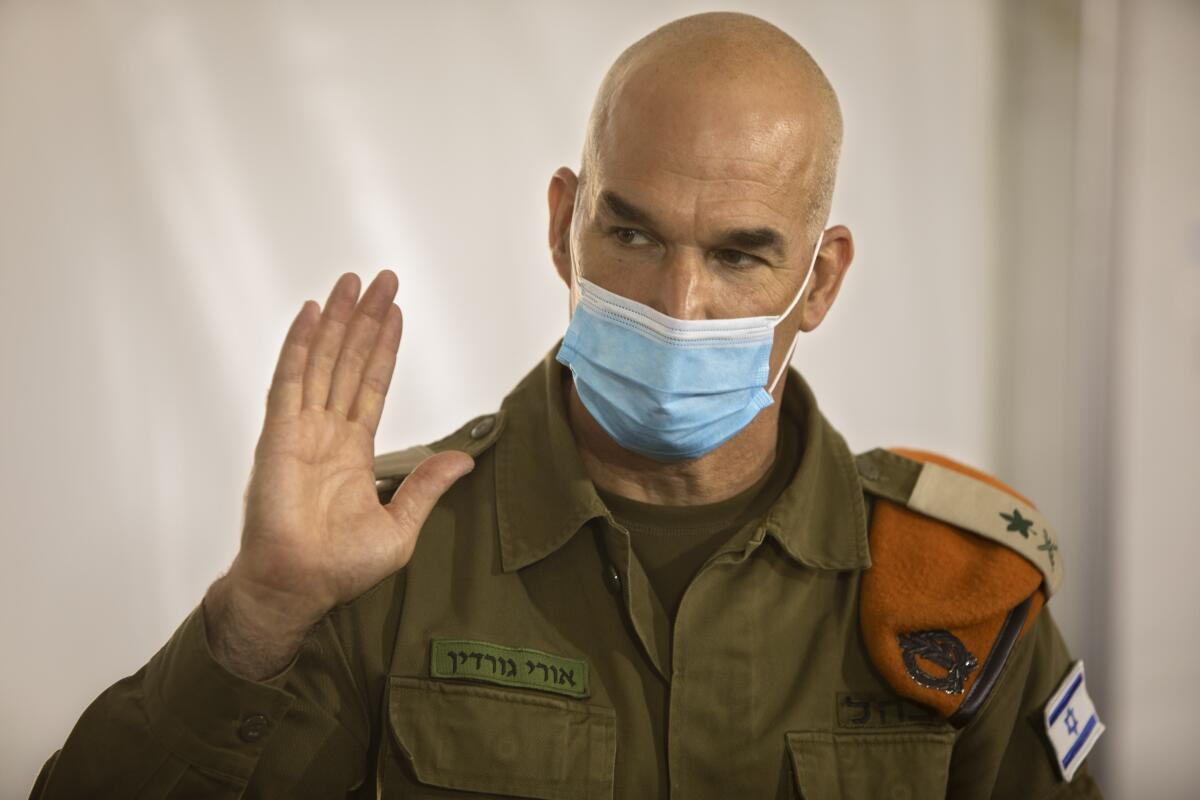

RAMLE, Israel — Over a three-decade military career, Israeli Maj. Gen. Ori Gordin has led commando raids, fought in wars and even earned a degree at Harvard. But he has never seen anything quite like his latest mission.

As head of the Israeli army’s Home Front Command, Gordin is now overseeing the military’s coronavirus task force, formed last month to bring one of the developed world’s worst outbreaks under control. Its main responsibility is taking the lead in contact tracing and breaking chains of infection.

“This is an operation on a different scale,” Gordin told the Associated Press, speaking in his first interview since taking over the Home Front Command in May.

Israel appeared to be a model of crisis management last spring, when the coronavirus first arrived. Authorities quickly sealed the borders and imposed tough lockdown measures, bringing the number of new infections down to just a few each day in May.

But officials reopened the economy too quickly, and the virus soon returned. Throughout the summer, the rate of new cases has remained at record levels, while the death toll has steadily climbed to more than 900 people.

Under heavy public pressure, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in July appointed Dr. Ronni Gamzu, a respected hospital director and former Health Ministry director, as the national “coronavirus project manager.”

An Israeli Cabinet minister says he has tested positive for the coronavirus

One of Gamzu’s first acts was to turn to the military for help, giving it the critical mission of cutting the chain of infections.

“You have to have the best operational forces, and in Israel, it’s the IDF,” he told journalists recently, referring to the Israel Defense Forces.

Founded in the wake of Iraqi Scud missile attacks on Israel during the 1991 Gulf War, the Home Front Command serves as Israel’s civil defense force. It helps maintain the country’s network of bomb shelters and air-raid sirens, and is trained to assist civilians during wars and natural disasters. It has sent rescue teams around the world to help countries coping with earthquakes, tsunamis and other emergencies.

For months, the command has been managing a network of coronavirus hotels, providing both isolation facilities and recovery services for infected people with mild symptoms. Its soldiers have also distributed food and supplies in hard-hit areas — including communities that have had little contact with the military, such as Arab towns and ultra-Orthodox Jewish neighborhoods.

A coronavirus lockdown has compounded misery in Gaza, where many were already struggling to get by amid a crippling blockade by Israel and Egypt.

Morad Ammash, the head of the municipal council of the Arab town of Jisr al-Zarqa, said the command worked well with his community when it dealt with an outbreak in March.

“They helped us with public information, managing the system, handing out food to the needy,” he said. “A good connection was formed.”

Gordin said public trust in the military is perhaps his most important asset. He said the army’s experience in emergency management and its huge pool of manpower also are key strengths.

Working under the direction of the Health Ministry, his task force acts largely as a coordinating and support body for civilian authorities in four key areas: expanding the number of tests; working with labs to speed up the results; interviewing those infected to identify who has been in contact with them; and quickly placing those at risk into quarantine.

Air travel to Israel has declined due to coronavirus restrictions, but the final journey of Jews wishing to be buried in Israel continues.

It is also working closely with municipalities, other government ministries, medical rescue services, police, and public and private labs to help streamline the national response.

“It’s like the management of one large factory,” Gordin said. “I can bring them all to one table and cooperate effectively and synchronize them in an effective manner.”

At the Home Front Command’s headquarters in central Israel, the task force has already set up a situation room. On a recent day, masked military officials sat alongside officials from the Health Ministry and other government ministries, representatives of municipalities and healthcare providers, plotting strategies as they analyzed data on large TV screens.

Upstairs was the “hotel unit,” where workers keep tabs on the thousands of people staying in the 25 facilities the force is managing. In nearby military tents, dozens of uniformed soldiers sat in front of computer screens, interviewing newly infected patients to retrace their steps and contacts.

A wave of demonstrations is sweeping Israel against Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his perceived failure to handle Israel’s coronavirus crisis.

Epidemiological experts from the Health Ministry, including an Arabic-speaking nurse from the Druze community, hovered about to offer guidance and answer questions. The contact-tracing data are fed in real time to the Health Ministry.

“Our goal is to stop the chain early on,” Gordin said. “If you don’t do it fast enough, it’s not relevant.”

Israel is not the first to enlist the military in the war on the coronavirus. Throughout Latin America, soldiers have delivered food, monitored traffic and and enforced stay-at-home orders, while in China, the Communist Party’s military wing brought some 1,400 doctors, nurses and experts to the city of Wuhan, the epicenter of the pandemic, to build two hospitals and treat patients early this year.

A military-led task force in Australia has helped local authorities with contact tracing, and Spain announced last week that the military is offering 2,000 soldiers to regional governments to assist in contact tracing.

Given Israel’s relatively small size and population of just 9 million, the new task force appears to be among the world’s most comparatively ambitious efforts. It already has enlisted 2,300 soldiers and expects to soon hit 3,000, in addition to the many civilian local officials and medical professionals.

While the task force is still in its early stages, Gordin said it has already been able to increase the number of daily tests and shorten the time for receiving results. Soldiers have conducted almost 2,000 interviews.

“I think that by Nov. 1 we should be in control of the situation. That’s our desire,” he said.

Despite the ambitious goals, the country faces some serious obstacles.

An Israeli jewelry company is working on what it says will be the world’s most expensive coronavirus mask, a gold, diamond-encrusted face covering.

Medical professionals say the nation’s epidemiological system is overstretched after years of government neglect.

Gamzu, the national coronavirus project manager, has also found himself feuding with politicians and powerful interest groups, all while trying to avoid another national lockdown.

He has been clashing with politically powerful religious parties, for instance, over his refusal to allow traditional September pilgrimages to the grave of a revered rabbi in Ukraine. Arab communities continue to hold large weddings, a popular custom despite the high infection rate plaguing the Arab population. The reopening of schools and upcoming Jewish high holidays also will present challenges.

Dr. Nadav Davidovitch, chairman of Ben Gurion University’s school of public health and a member of a board of advisors helping Gamzu, said there is no guarantee of success, but agreed that bringing in the army is a good move.

“If the right balance is achieved with the oversight and guidance and training by the Ministry of Health, I think that’s the right way of doing it,” he said. “This should have been done long ago.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.