The family arrived at Los Angeles International Airport on the way home from a Mexican vacation that had been short-lived and unpleasant. They had been exhausted, the father was battling a nasty stomach bug, and even before they settled into their Cancun hotel, they got word of the sudden death of the wife’s mother in their hometown: Wuhan, China.

The couple and their toddler son wanted to get back for the funeral and planned to be at LAX just long enough to switch planes. But as they passed through Tom Bradley International Terminal on Jan. 22, the father was overcome with a fever and body aches and approached a customs officer for help.

The family did not make their flight that Wednesday night and, indeed, would not return to China for more than a month. The father, Qian Lang, became the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in Los Angeles and the fourth in the United States. He remained the sole patient diagnosed with the virus here for five weeks, passing most of that time in top-secret isolation at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

The 38-year-old salesman played an important role, not widely known until now, in a frantic race to understand the deadly new virus before it hit the United States in full force. Public health officials and researchers looked to him as a real-time, flesh-and-blood case study.

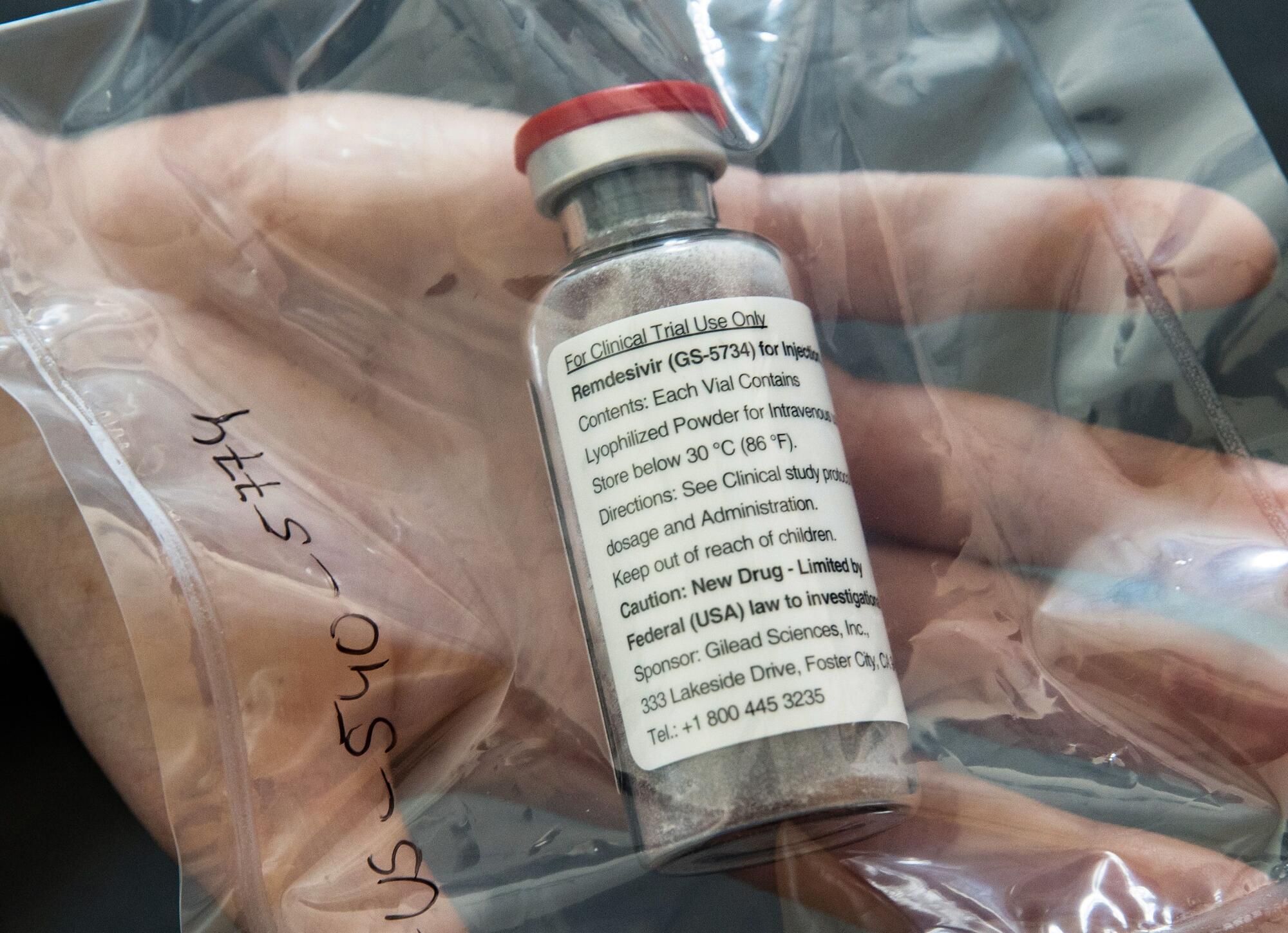

From Qian (pronounced Chee-an), they gleaned early insights into the protection of healthcare workers, contact tracing and treatment. He was the second virus patient in the world to take the drug remdesivir, then experimental and now a standard therapy for those seriously ill with COVID-19.

For his family, Qian’s illness and recovery meant a strange and frightening sojourn in California. Though his wife and preschooler son tested negative, they stayed with him at Cedars-Sinai in the closest approximation of a domestic life infection protocols allowed: adjoining isolation suites separated by glass.

“We realized that is a huge burden on that poor woman,” L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer recalled. “By herself. Didn’t really speak the language. And taking care of a child full time around the clock in basically a very confined space.”

Ferrer and other health professionals said medical privacy laws prevented them from identifying Qian by name or divulging details of his care. But they agreed to talk generally about his case, which has been included in half a dozen prominent research studies. In one, he is called “CA1.” In another, “Patient 9.”

This story is based on those published scientific papers, interviews with public health officials and clinicians, ambulance records, an airport police report that named Qian and his wife, and a February interview he gave to a Chinese news blog, Deeper Wuhan, under a pseudonym.

Qian did not respond to messages left for him on a social media account. The anonymous author of the Wuhan blog article said she reached out to him on behalf of The Times, but he declined an interview request.

::

‘the Husband self-reported to one of their officers that he needs medical attention and may be suffering from flu since he has a bad cough and ... running nose’

— an airport police report

Americans weren’t paying a lot of attention to COVID-19 when Qian landed at LAX. President Trump’s impending impeachment hearing and the upcoming Iowa caucuses dominated the news, and around water coolers in L.A. — and there were still water coolers then — the talk was less likely about the new virus in Wuhan than “Parasite’s” shot at a best picture Oscar or LeBron James’ quest to overtake the still-alive Kobe Bryant on the NBA’s all-time scorers list.

Inside L.A. County’s public health department, however, epidemiologists and other experts were keeping watch for the first inevitable cases. They spoke regularly with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. By mid-January, there was enough awareness about the virus in the medical community that doctors were phoning the county with suspected cases.

“There was a lot of flu at the time,” said Dr. Sharon Balter, the county director of acute communicable disease control, recalling hundreds of calls her colleagues received. Many clearly were not COVID-19, she said, but “we anticipated that with a large amount of travel between L.A. and China there would eventually be a case, so we were definitely preparing for it.”

Each suspected patient had to be treated as if infected until test results came back from the CDC lab in Atlanta, the only testing facility at the time. More than once, Balter and her colleagues were convinced they had a bona fide virus patient, only to get a negative result from Georgia.

It was the third week in January when COVID-19 was detected on American shores. On Sunday, Jan. 19, a man sought treatment at a Washington state clinic for a cough and fever. He became the first person in the U.S. diagnosed with the virus. One day later, a Chicago woman was hospitalized for pneumonia. She became the second. Orange County got the third case that Wednesday. All three had been in Wuhan shortly before falling ill. All would survive.

Qian was next. He, his wife, Liu Ying, and their son set out from Wuhan early that week for a long-planned Caribbean vacation. They were aware of the virus, but “pretty at ease overall” about it, he later told the blog. The local health commission in Wuhan was reporting only 62 cases and two deaths at the time of their Jan. 19 departure. Health officials there noted that many of the stricken had only mild symptoms, and the city’s top public health doctor told a government news broadcast that “the infectivity of the new coronavirus is not strong.”

Still, Qian, a physician’s son steeped from a young age in safety protocols, took precautions public health officials would later cite as significant. On flights from Wuhan to Mexico City, he wore a mask, one of the few aboard to do so, and blasted the overhead air vents to increase circulation around his family.

Connecting through LAX on their way to Mexico, the couple and their child were screened by the CDC, but displayed no symptoms. Qian told the blog that his temperature was so low that a screener joked, “Are you a vampire?”

The family planned to spend time in Mexico City before heading on to their Caribbean destination, but they were gripped by fatigue and weakness and Qian contracted giardia, a common parasite that afflicts travelers with diarrhea. The family rarely ventured from the hotel. On the second day, Liu’s father phoned them to say her mother had taken ill with a fever. The next day, he reported that he had summoned an ambulance, but it was too late and she had died.

The family packed their bags and headed back through LAX. After touching down, Qian felt hot and, as he told the blog, “powerless.” Going through customs “the Husband self-reported to one of their officers that he needs medical attention and may be suffering from flu since he has a bad cough and ... running nose,” an airport police sergeant wrote in a report. He noted that the family was “from Wuhan, where the Coronavirus originated.”

The situation in their hometown had become dire in the three days since they’d left. Authorities were reporting hundreds of new cases, and rather than downplaying the threat, officials were preparing to lock down the city of 11 million to stop the virus’ spread.

Told of Qian’s connection to Wuhan, his symptoms and the sudden death of his mother-in-law, CDC personnel at the airport suspected the virus and called for a Los Angeles Fire Department ambulance specially equipped for COVID patients. It took the family to Cedars-Sinai’s Marina del Rey hospital.

‘The information coming out of China was increasingly concerning. At the time, there was no known treatment.’

— Dr. Jonathan Grein, Cedars’ director of epidemiology

The crew, dressed head-to-toe in protective gear, allowed the boy and his parents to sit side by side on the stretcher, Qian told the blog, adding of the American authorities, “Their response is very professional, timely and fast!”

Tests sent to Atlanta confirmed Qian was positive and Liu and their son were negative, though she had the common flu. The family was transferred to Cedars’ flagship on Beverly Boulevard, a celebrity favorite where Kim Kardashian gave birth and Frank Sinatra died. The blog did not name the hospital, but Qian described it as “a very famous medical institution” and photos of an isolation unit posted with the blog entry show personnel in blue-green scrubs such as those worn at Cedars.

Providing top-secret care was second nature at Cedars, and many who worked there were unaware of the presence of a COVID patient. One employee who spoke on the condition of anonymity said the family was installed in a special wing of the fourth-floor pediatric intensive care unit protected by a security guard. A photo on the blog shows Qian’s room decorated with “Minions” cartoon characters such as the ones the employee said decorate the walls of Cedars’ Pediatric Intensive Care Unit.

The family’s electronic medical records were designated “break the glass,” a classification that dissuades employees from spying on famous patients by requiring them to reenter their password and state a reason for viewing the records, the employee said. The employee requested anonymity to speak publicly about patient care.

The Cedars team took aggressive steps to quarantine the hospital’s COVID-19 patient, following protocols created for Ebola and other pathogens, said Dr. Jonathan Grein, Cedars’ director of epidemiology. The measures were more extreme than in current use for COVID-19, but at the time, Grein said in an interview, the team was “kind of looking in the void and not sure what’s going to happen.”

And then Qian took a turn for the worse.

Grein described a nerve-racking time, with frequent conference calls arranged by the CDC to consult with the clinicians caring for the 11 other patients scattered across the United States. Of them, Qian was the most severely ill.

“The information coming out of China was increasingly concerning,” Grein said. “At the time, there was no known treatment.”

Patricia Dowd of San Jose, who died Feb. 6, was the first known COVID-19 fatality in the U.S.

For days, the chief medical officer of the CDC’s influenza division, Dr. Tim Uyeki, had been trying to recruit COVID-19 patients for an experimental treatment. Remdesivir was an experimental antiviral drug developed a decade earlier by Gilead Sciences and tested briefly on Ebola victims. It was not especially effective: Of 175 test candidates, 93 had died — most from Ebola, and one of them potentially from the treatment.

Qian initially experienced only run-of-the-mill flu symptoms that could be treated with pain reliever and cough medicine. But in the second week, his temperature spiked, his lungs filled with fluid and he struggled to breathe. He was placed on oxygen and monitored around the clock. One night, with his wife and child on the other side of a glass window, he typed out a will on his phone, he told the blog.

Doctors told Qian about the experimental trials with remdesivir, but he was apprehensive, according to the blog. Twice, he told doctors he didn’t want to try it.

Qian’s condition remained grave. As he struggled to breathe, he told the blog, he often thought of the bravery his young son had shown when the family had undergone blood tests, clenching his small fist and shouting to his father, “Dad, you have to hang in there!”

The third time doctors approached him, he agreed to try remdesivir. An interpreter read him a five-page consent form over the phone, and then the drug was administered intravenously.

After a day, his fever dropped. Soon, he no longer needed the oxygen.

“The doctors were amazed,” he told the blog, adding that one asked if he felt his recovery was due to the medication or his own immune system. “I told him I think it was both. A calm, optimistic attitude also helped.”

Qian’s case was included in an encouraging study of remdesivir published in the New England Journal of Medicine last month. Fifty-three patients hospitalized for the virus were given the drug in various countries. Seven died. But 68% improved.

Despite continued concern of adverse effects, it is so widely used now that hospitals from India to San Francisco report shortages.

While Qian’s recovery was thrilling for the medical team, it didn’t mean he and his family could go home. Little was known about how long patients remained contagious. Grein said officials decided it was safest if he remained in isolation, and after 27 days at Cedars, he was moved to another secret medical facility.

The county kept close tabs on the airport first responders and Cedars employees who had contact with the family, looking for signs of illness. At the time, it was not yet known that asymptomatic people could spread the virus.

Dr. Howard Chiou, a CDC epidemiologist, recalled being interrupted in the middle of a weekend dinner to help on Qian’s case. Chiou, who is fluent in Mandarin, worked directly with the family to develop a list of places and people for contact tracing.

“Case investigation and contact tracing is really hard, complicated work that requires building a strong relationship and trust in a very short amount of time,” Chiou said. “This case was a great reminder that language and cultural skills are critical in building trust and rapport.”

Public health officials reached out to their Mexican counterparts so the hotel could be made aware of the case. They also alerted passengers seated near the family on the flight from Mexico City as well as the plane crew.

In the end, no one is known to have been infected by Qian. Some healthcare workers developed respiratory symptoms, but tests came back negative.

‘It really helped us to think through the issues that people would face in isolation and quarantine, and especially travelers or people without safe places to stay.’

— CDC epidemiologist Dr. Howard Chiou

There has been no recurrence of the COVID strain that infected Qian among thousands of samples shared by researchers around the world, said epidemiologist David Engelthaler, the head of the infectious disease arm of Arizona’s Translational Genomics Research Institute. He said that absence suggests Qian did not infect others and was “a dead end” for the virus, though he cautioned that testing was limited. Most people working at Cedars then were not told a COVID patient was in their facility and were not offered testing.

“I do not think there was spread,” Balter said. Public health officials say they believe the precautions Qian took while traveling and his request for help kept others safe.

“He was very good about wearing his mask when around [his family] and on the plane,” Balter said.

By mid-February, COVID had crept around the world and was starting to ravage South Korea and Italy, but Qian was still L.A.’s only known case. Worried about the toll the isolation was taking on Qian’s wife and son, public health workers bought toys for the boy and worked to make sure the family had food they liked.

A cluster of deaths, some involving infants, is under scrutiny amid questions of whether the coronavirus lurked in California months before it was detected.

Ferrer said they learned from the family that for people to isolate successfully, they need personalized support from health workers.

“It made a big difference. It wasn’t just that they got good clinical care,” she said.

Chiou, the CDC epidemiologist, agreed, saying, “It really helped us to think through the issues that people would face in isolation and quarantine, and especially travelers or people without safe places to stay.”

On March 4, 42 days after Qian sought help at LAX, the county announced it had identified six more cases of COVID-19. In retrospect, public officials said, strict limitations on testing and ignorance of the virus’ asymptomatic spread prevented public health officials from detecting many people already infected.

“We clearly had other cases,” Ferrer said.

Qian was still in isolation when the story of his care in the U.S. was published in the Wuhan blog. Relations between China and the United States were stressed, and worsening. Some readers were cynical about the story’s favorable account of U.S. medical care.

“This person was cured by remdesivir without paying a penny,” one poster wrote. “I highly doubt this article.”

It’s unclear whether Qian or the Chinese Consulate, which was kept informed of his case, paid anything. Cedars and the consulate declined to answer questions about his case, citing patient privacy.

For his part, Qian was appreciative.

“He did send a very, very grateful thank you note to the department,” Ferrer said.

Times staff writer Alice Su in Beijing contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.