Politics, not necessarily science, seen as key driver of Russian vaccine claim

The name might just say it all.

In a global first, Russia announced Tuesday that it had developed a ready-for-use coronavirus vaccine. And, in a not-at-all-subtle nod to a decades-old triumph, the formulation is to be marketed under the brand “Sputnik V.”

Against a backdrop of intense international competition to develop the first working vaccine for the virus that has infected more than 20 million people around the world, the name harks back to another fabled rivalry: the Cold War-era space race between the United States and the then-Soviet Union.

The Soviets’ successful 1957 launch of Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite, set off anguished Cold War hand-wringing over whether the U.S. was being bested by its nemesis in the wider realm of technology and science. The Sputnik episode galvanized the landmark American space effort that culminated in the 1969 moon landing.

Infectious disease experts are casting considerable doubt on the expected efficacy and safety of the Russian vaccine, which was personally touted Tuesday by President Vladimir Putin despite not having been subject to Phase 3 clinical trials, the universally accepted prerequisite for wider use.

“I know that it works quite effectively, forms strong immunity and, I repeat, it has passed all the necessary tests,” Putin told a video gathering of government officials, according to state media.

Analysts called the announcement a clear move by Putin to shore up his sagging domestic political fortunes — and at the same time burnish Russia’s global prestige.

“This is a chance for Putin to position Russia as a savior,” said Judy Twigg, a senior associate with the Global Health Policy Center at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

But it also represents “a huge gamble on Putin’s part,” said Twigg, who teaches Russian politics and global public health at Virginia Commonwealth University.

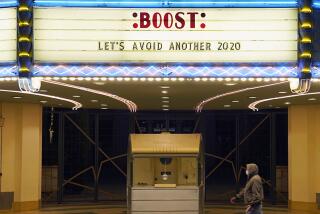

A genuine vaccine success, in addition to fueling a burst of national pride, would be a boon to Russia’s economy, battered like others around the world by virus-related shutdowns. If the vaccine fails, though, it would probably deepen public discontent and cynicism about Putin’s leadership, she and others said.

However deep the international scientific community’s reservations, even some close U.S. allies signaled interest.

Israel’s health minister, Russian emigre Yuli Edelstein, expressed hopes Tuesday for early discussions with Moscow about its vaccine.

Countries that already look more to the Kremlin than to the White House for leadership appeared eager to sign on.

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, a strongman leader in Putin’s mold, not only offered his country as a venue for clinical trials, but also volunteered to take part himself.

The Russian announcement immediately raised concerns that Putin’s claim might be prematurely embraced by President Trump, who has shown himself willing to tout unproven and even unsafe means of combating the virus.

His administration struck a cautious note, with Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar telling ABC’s “This Morning” that “the point is not to be first with a vaccine — the point is to have a vaccine that is safe and effective.”

But in the months since the outbreak began, Trump has often undercut his own public health experts. He waged an ongoing campaign in favor of the antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine, even after studies suggested it was not only ineffective as a coronavirus treatment, but also carried serious risks.

Trump also drew widespread ridicule when he suggested that injecting a disinfectant like bleach could be a potential treatment for the virus.

The Russian announcement also coincides with renewed criticism from congressional Democrats and others over Trump’s deferential stance toward Putin.

Critics point to the president’s recent failure to confront Putin over reports that Russian intelligence offered militants in Afghanistan bounties for killing U.S. troops, and his dismissal of new intelligence reports that the Kremlin is actively working to aid Trump’s presidential candidacy by denigrating his rival, former Vice President Joe Biden.

Trump has long insisted that getting along with Russia would pay dividends — a view that could be bolstered if Moscow proves a leader in countering a pandemic that has inflicted crippling social and economic consequences on much of the world.

“The Russians have sought from the beginning of this crisis to use it as kind of a fulcrum for shifting the international discourse, especially in the West, away from ‘Russia is an outlier, a problem and a provocateur’ to ‘Russia is a vital partner,’” said Matthew Rojansky, a Russia expert who directs the Kennan Institute at the Wilson Center, a Washington think tank.

Echoing Trump’s tendency to make endorsements based on personal ties and preferences, Putin brought a family connection to the proceedings, telling senior aides that his daughter had been treated with the vaccine, suffering no ill effects after two doses other than a slight fever.

The vaccine, developed by Moscow’s Gamaleya Research Institute, is expected to be put into mass production by year’s end, according to the Russian business conglomerate Sistema, its distributor.

The first doses of two will be made available within weeks to front-line workers including medical personnel, then other public workers such as teachers, with a wider rollout expected in October, Russian reports said.

Dozens of possible vaccines against COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, are in development around the world, and several of those have entered Phase 3 trials, according to the World Health Organization. Moscow has heatedly denied accusations that Russian hackers tried to breach research platforms in the United States, Britain and Canada.

The Russian formulation taps into decades of research that formed the basis for other vaccines, including for the Ebola virus. Public health experts said, though, that there was scant proof to support even slender prospects for a genuine breakthrough.

“It may be OK — the construct they are using is quite well-known,” said Eskild Petersen, an associate professor in clinical medicine and infectious diseases at Aarhus University in Denmark. “But they skipped the trials, so we simply don’t know.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.