What caused the Beirut blast seems clear; who, and why, is another question

BEIRUT — Before the mass explosion that rocked Lebanon on Tuesday, many thought the country had already hit rock bottom.

Beirut had begun to resemble the scene of a dystopian film. Thanks to a deepening economic and currency crisis that has led to shortages of essential items including fuel, the streetlights were off.

With government-provided electricity coming sometimes only a couple of hours a day, diesel generators were running nearly nonstop, coating the city in a perpetual haze of smog. The number of beggars on the street — many of them children — had multiplied.

The only thing that could make the situation worse, many thought, was another war.

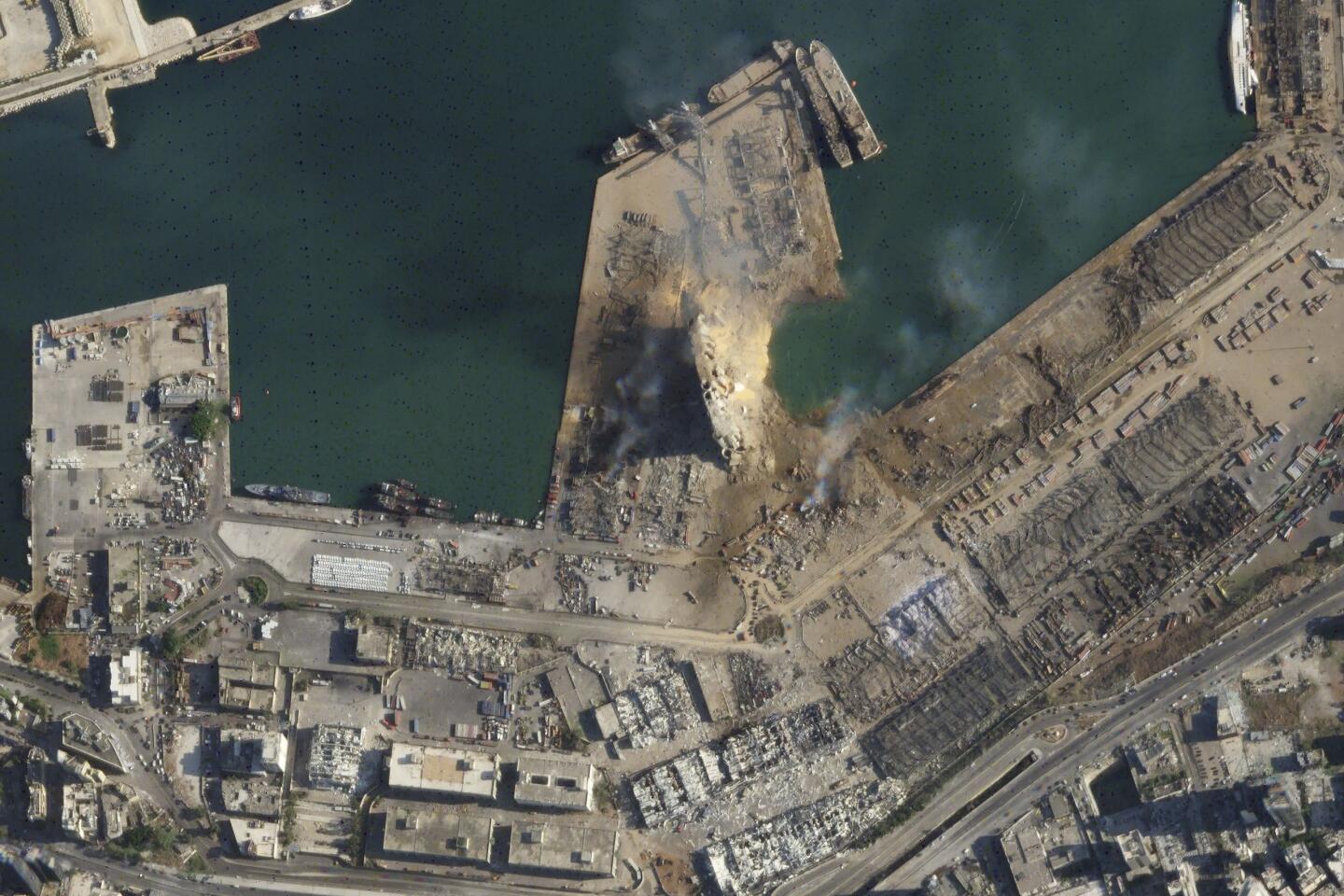

But the blast that came, in the end, was, according to all official accounts, neither a terrorist attack nor an Israeli strike. Rather, it was the result of an apparently accidental fire that detonated a stockpile of confiscated ammonium nitrate that had been stored in a hangar in the Beirut port for years — the result, as many saw it, of the same negligence by those in power that had led to the economic crash.

“Now came this massive crisis — because everything else that happened before it wasn’t enough. Our state is doing everything it can to kill us,” said Gisele Nader, a volunteer with Dafa Campaign, an initiative that was distributing food, water, clothing and other necessities Wednesday to families whose homes were damaged in the blast.

“I was here throughout the war, but I’ve never seen the country so damaged,” Nader said.

And thanks to the preexisting economic crisis, it may now be much harder for Lebanon to bounce back from the after-effects of the explosion, which killed more than 100 people, injured an estimated 4,000, left as many as 300,000 people homeless and caused an estimated $3billion in damage.

As of Wednesday, civil defense volunteers were still combing through rubble looking for the bodies of the missing, while family members were desperately making the rounds of hospitals and posting pictures on an Instagram page set up to help Beirutis find missing loved ones.

“If this incident, this criminal incident, happened many years back I would tell you, it’s problematic, but we can survive,” said Jad Chaaban, a Lebanese economist and activist. “But right now, this is a question of Beirut becoming a failed city and a completely broken city if people do not mobilize very quickly and support it.”

The fact that the destruction comes on top of a currency crisis means that many property owners will probably not be able to access the dollars needed to pay for imported reconstruction supplies. Since September, the price of the dollar has risen from its officially fixed rate of around 1,500 lira to a black-market rate that is currently around 8,000.

As a result, many Beirut residents are now facing the prospect of months sleeping in apartments with broken windows.

Tony Naqour, an insurance office employee who lives in the heavily damaged area of Gemmayze, a largely Christian neighborhood filled with trendy bars and restaurants that was one of the areas hardest hit by the explosion, had joined some young men from the area to help clean the rubble from a neighborhood soccer club Wednesday.

Naqour said Tuesday’s explosion, which he initially thought was a bomb dropped by a warplane, had blasted out the windows of his house.

“Where are we going to get glass now? The price of a meter is going to go to $300,” he said. “So, what are we going to do? Sleep in the street? We’ll stay in the house without glass in the windows and smell the stench of the garbage at night.”

Naqour’s house fared better than many. Historic buildings that had been left untouched by past wars have been hollowed out by the explosion, and most of their residents had by Wednesday moved to stay with friends and relatives, in their family homes in the mountains or with strangers who had posted offers of housing on the internet.

Some had stayed on the streets.

Randa Hayat, who was sitting outside her half-demolished building with her husband, his foot bound in a cast, said she had been outside Tuesday evening when the blast happened and, terrified to enter the building afterward, had slept in the blasted-out storefront next door.

You can deal with militias and armies, the owners of Beirut’s famous Barbar restaurant say, but you can’t make friends with the coronavirus.

“We’ve been out here all night,” she said. “There are no words to explain what happened, no words.”

Lebanese officials have promised aid for those displaced by the crisis and to hold those responsible accountable.

“All those responsible for this catastrophe will pay the price,” Prime Minister Hassan Diab said in a speech Tuesday. “This is a promise I make to the martyrs and the injured.”

And on Wednesday, the Lebanese government declared a two-week state of emergency and ordered port officials put under house arrest while launching an investigation into why a 2,750-ton stockpile of ammonium nitrate had been stored in a hangar at the port since being confiscated from a ship in 2013, despite the customs chief having warned of the danger of leaving it there.

The tragedy garnered attention worldwide and offers of international aid, with nations including France, Russia and Egypt sending medical staff and equipment, and others, including Australia and Norway, pledging money for humanitarian support.

Even Israel, which had initially been blamed by many in Lebanon for the blast after heightened tensions on the borders and increasingly frequent flyovers by surveillance aircraft in recent weeks, offered humanitarian assistance.

While the international aid will help offset the costs of responding to the disaster, Chaaban said, it will not be enough to help the country out of its underlying economic problems. Lebanon has sought $10 billion in assistance from the International Monetary Fund, but talks have stalled, and other potential donors have been reluctant to offer aid without an IMF deal or concrete movement on economic reforms.

Chaaban said that while the new aid is welcome, “whatever aid we get now is new aid on things that are newly destroyed. This will not help us get back our electricity, our environment, our basic infrastructure, for which we needed support in the beginning.”

For many Lebanese, it’s hard to see a way out of the morass. Asked how he sees the future of the country, Naqour demurred.

“I can’t tell you what’s the future ahead of us,” he said, turning to the other men around him, at work sorting through debris. “What do you think, guys? What’s the future of the country? Does anyone have an answer?”

No one did.

Sewell is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.