Minneapolis braces for overnight protests after police officer is charged with murder

MINNEAPOLIS — The death of a black man and a murder charge against a white police officer on Friday forced the Twin Cities to reckon with a history of discrimination that belies a progressive reputation shattered by fires, riots and rage that have ignited a nation.

Former Officer Derek Chauvin, 44, was charged after a bystander’s video sparked three days of protests and looting that culminated in the destruction of a nearby police station Thursday night. Chauvin and three other officers involved in restraining George Floyd have been fired, but the others have yet to be charged, a prospect for many that has left justice unresolved.

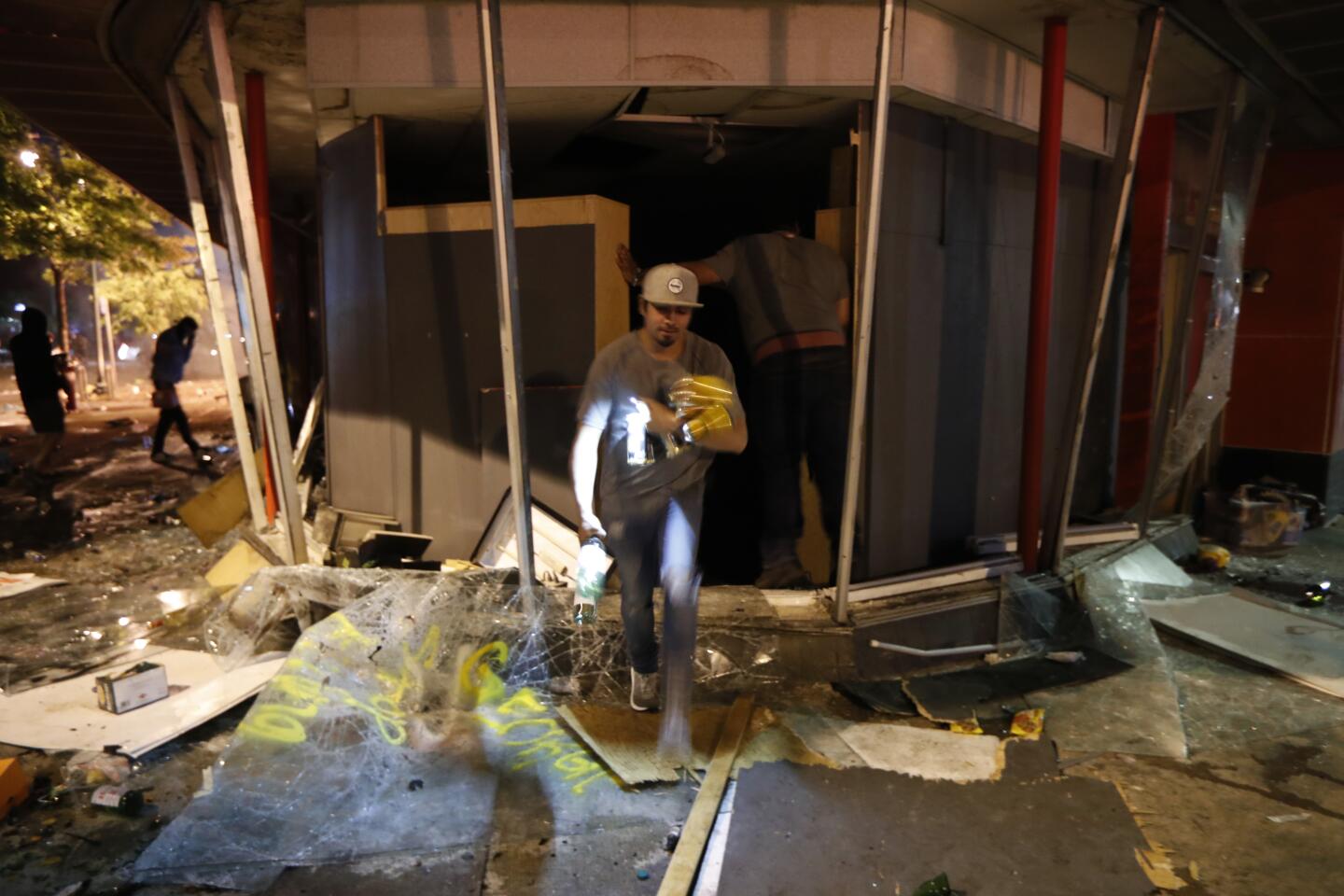

As buildings smoldered and looting continued late Friday — and as both the country and this city confronted yet another flashpoint over race and policing — it was unclear if curfews, the deployment of the National Guard and other measures would be enough to stop the unrest. Across the nation, protests flared, bullhorns blared and police helicopters ominously circled city skies.

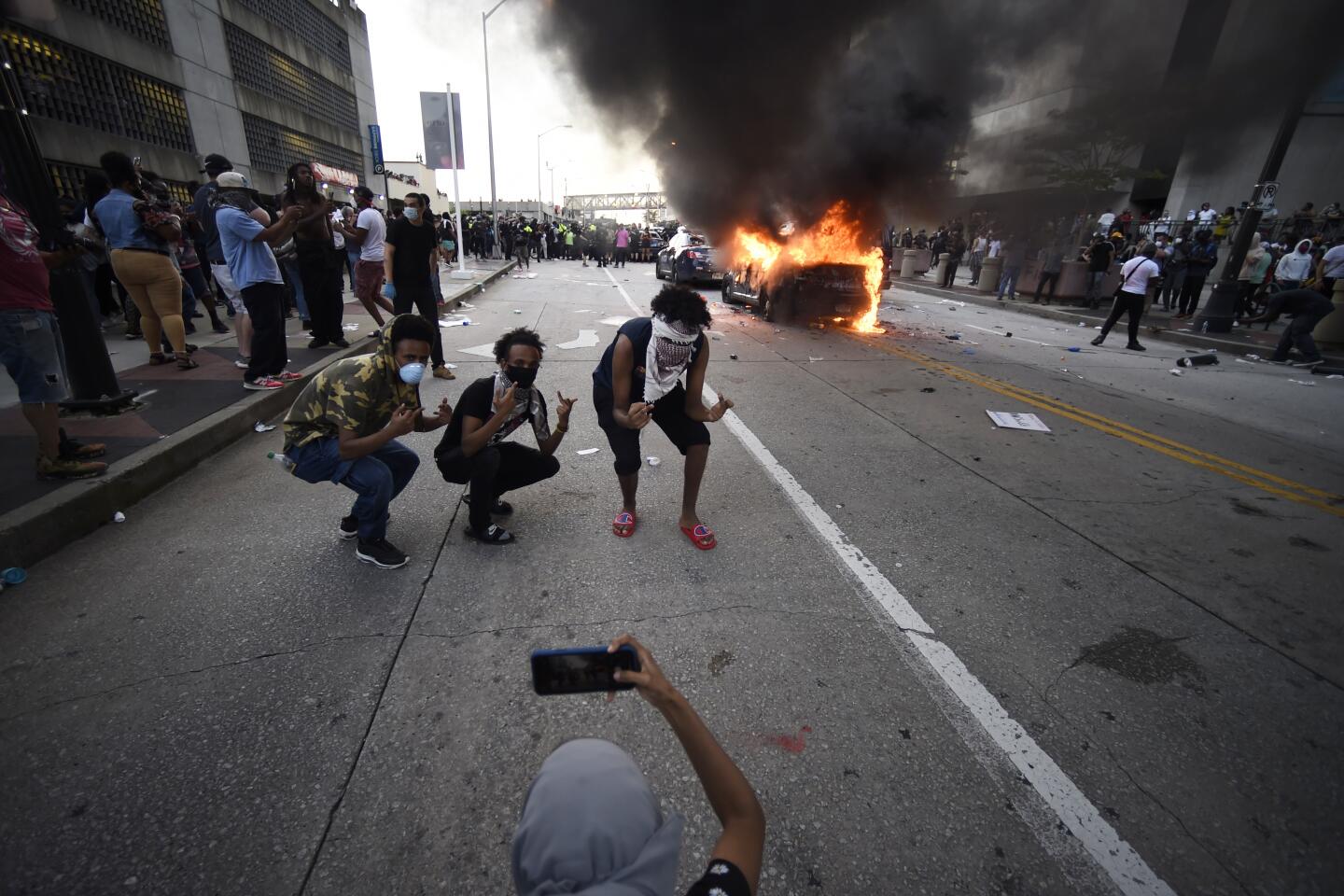

A police car was torched in Atlanta, sirens screamed as protesters gathered in downtown Los Angeles, and demonstrators in Minneapolis waited for nightfall. It was all brought about by another disturbing video that had gone viral at a time America was confronting the coronavirus and political divisions that again exposed deeper inequalities.

Speaking for the first time about the protests at the White House late Friday, President Trump said, “We can’t allow a situation like happened in Minneapolis to descend further into lawless anarchy and chaos. It’s very important, I believe, to the family, to everybody, that the memory of George Floyd be a perfect memory.

The Minneapolis officer fired after George Floyd’s death was involved in police shootings during his 19-year career.

“The looters should not be allowed to drown out the voices of so many peaceful protesters. They hurt so badly what is happening,” he said, alluding to previous comments on Twitter.

The Floyd family’s attorney called Chauvin’s arrest “a welcome but overdue step on the road to justice.”

“We fully expect to see the other officers who did nothing to protect the life of George Floyd to be arrested and charged soon,” attorney Benjamin Crump said.

Michael Freeman, prosecutor for the surrounding County of Hennepin, said at a Friday briefing that Chauvin was the first of the officers charged because “we felt it was important to focus on the most dangerous perpetrator,” and added that the case “has moved with extraordinary speed.”

Freeman said he anticipates the other officers will be prosecuted, but declined to specify what charges they could face.

It’s uncertain whether Chauvin knew the 6-foot-7-inch Floyd, 46, before he restrained him while responding to a report that Floyd had passed a fake $20 bill at a convenience store Monday. Both worked security for the last year at a local club, El Nuevo Rodeo, according to former owner Maya Santamaria. Floyd worked inside while Chauvin coordinated a team of off-duty police officers securing the outside, Santamaria said. She wasn’t sure if they ever met.

Santamaria hired Floyd to work part-time and didn’t know him well, but said she worked with Chauvin for 20 years. The former officer could be relaxed and mellow, but also badge-heavy, using his authority to unsettle larger men, she said.

“He had to use the power of the badge to intimidate people that in a fair fight would have been on the winning side,” she said. “He did use his power as a police officer a little more than I would have liked.”

Chauvin got along with Latino customers, but did not like to work events that drew African American crowds, according to Santamaria. When he did and there was a fight, he would spray people with mace and call for police backup, which Santamaria called “overkill.”

When she first saw the video of Chauvin kneeling on Floyd’s neck, Santamaria said she recognized the officer immediately and started shouting at her cellphone screen, “My God — get off of him! What are you doing?”

“I never would have thought he was a murderer. I never would have seen him in that light. I would have thought he would be reasonable,” she said.

George Floyd’s death at the hands of police quickly became a symbol of inequality

She said was glad to see the former officer charged.

“The streets will be safer tonight because of it. We need justice to be served in this country so we can heal,” she said. “He needs to be made an example out of. That way, maybe cops will think twice before doing this.”

Those familiar with the police and city’s history were dubious.

“I don’t think people are going to be appeased as far as justice is being done — the problem goes back years,” said Dave Bicking, a longtime board member at Communities United Against Police Brutality.

“We have some of the worst disparities in the country in education, employment and criminal justice. They’re known here to people who care,” said Bicking, who served on a civilian review board for the Minneapolis Police Department years ago, before several recent high-profile officer-involved deaths. “Despite all the happy talk about police and community relations, nothing has improved.”

Several hundred people who gathered Friday at a makeshift memorial to Floyd at the corner where he was restrained — while gasping, “I can’t breathe” — were upset that only one of the former officers had been charged.

The crowd mostly dressed in black held signs and rode bicycles across traffic lanes while some held up sign that read “We are not thugs.”

Before an 8 p.m. curfew was imposed in the Twin Cities and some suburbs, several hundred protesters stopped traffic on a bridge near downtown Minneapolis, marching onto an interstate. Outside the charred 3rd Precinct police station on the city’s south side, protesters vowed to defy the curfew until all four officers were charged. There were fears that the 4th Precinct on the city’s north side also would be targeted; business owners boarded up windows and National Guard troops took positions.

“Those four police officers all need to be charged with murder. I don’t know what this city is going to do. I don’t know about my people. But I don’t think one police officer in jail is enough,” said Anjel Carpenter, 55, an African American registered nurse who lives nearby and described a pattern of racial profiling.

“The police are terrible here,” she said.

She and others in the crowd praised the sympathetic response of the city’s young mayor, Jacob Frey, and a like-minded City Council that includes two newly elected black transgender members. Some expressed approval for Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo, a Mexican-African American who has attempted to overhaul the department, addressing racial profiling in arrests and police brutality.

Frey, 38, a civil rights lawyer, campaigned on issues of police reform and racial inequality when the then-city councilman ran for mayor in 2017. He posted on Facebook, “The man who killed George Floyd has been charged with murder. This [is] an essential first step on a much longer road toward justice and healing our city.”

But residents also see the city’s leadership as the new guard, operating against a backdrop of discrimination in education, employment and housing so ingrained and reinforced by state leaders, they’ve nicknamed it “Minnissippi.” For people of color, the “Minnesota nice” facade often camouflages microaggressions, said Angelique Kingsbury.

“You never really know where you stand with people,” said Kingsbury, 47, who has black, white and Native American heritage. “It’s very well veiled, and some of the so-called people that are progressive, they perpetuate it just as much.”

That includes white progressives who have quietly benefited from systemic racist practices such as redlining, she said, which lead to more segregated neighborhoods and schools.

Kingsbury said she has darker-skinned friends who have recently been stopped while walking in their neighborhoods and asked “Do you belong here?” Last year, a security guard stopped her from taking selfies near a downtown mosaic while she was wearing a head wrap, asking, “Where are you from?” This in a city represented by progressive Democratic Rep. Ilhan Omar, the country’s first Somali American congresswoman.

Kingsbury was pleased to see the mayor quickly support protesters, condemn the officers involved and call the attack what she believes it was — not just an attack on Floyd, but an attack on communities of color in the city.

“He understands the hurt and the frustration that’s been bubbling,” she said of the mayor, whom she voted for.

Kingsbury said residents need to rally around the mayor so that he and other local leaders can confront state officials whose default seems to be to send in more law enforcement to quell the protests.

“We have a long way to go,” she said as she stood watching protesters near a mural of Floyd chanting, “Revolution.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.