News Analysis: Is the coronavirus crisis reason to worry about how other nations view U.S. leadership?

Maybe for the first time in decades we should begin worrying about what others are saying about us.

Jeremy K.B. Kinsman, a veteran Canadian diplomat, speaks of “continental drift” and “America’s evacuation of world leadership.” Swedish former Prime Minister Carl Bildt says “there’s not been even a hint of an aspiration of American leadership” in the global fight against the novel coronavirus. The distinguished Irish columnist and critic Fintan O’Toole, referring to the American response to COVID-19, asks: “Will American prestige ever recover from this shameful episode?”

Washington, we have a problem, and it goes beyond the virus and the million-plus Americans who have contracted the disease.

And as a result the globe has a problem — with America and its indecision and indiscretion, with the prospects for an ordered world, perhaps even with a world leadership vacuum unlike any since the decline of the Spanish empire at the beginning of the 17th century.

For three-quarters of a century the United States has been a world leader — in finance, science, education, popular culture, military capacity and, often but not always, moral power.

This country created a consumer culture without parallel in human history. It financed the rebuilding of the ancient states and famous cities of war-wrecked Europe. It sent researchers to laboratories to defeat polio and astronauts to the moon to realize an ancient yearning. Its songs were sung by billions, its films were viewed by millions, its political system set forth in its Constitution was copied by scores of nations. It dominated international councils — all while flourishing economically at home and addressing though not resolving long-festering questions of race and inequality.

Now, for the first time in living memory, it is possible to read a passage like this, from O’Toole in the Irish Times: “There is one emotion that has never been directed towards the U.S. until now: pity.”

The study of imperial decline is a hardy perennial in academic study carrels and university seminar rooms, occasionally bursting into broad popular debate; a prime example of the latter was the publication in 1987 of “The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000” by Paul Kennedy, a Yale professor.

But only now has the notion become more than an academic question.

Indeed, it is a question of great consequence, and not only internationally.

At home, President Trump may like the trappings of empire but he also believes that the American role sculpted by Franklin Delano Roosevelt during World War II and burnished by his successors, beginning with Harry S. Truman and extending all the way to Barack Obama, is a trap — or at least a money pit.

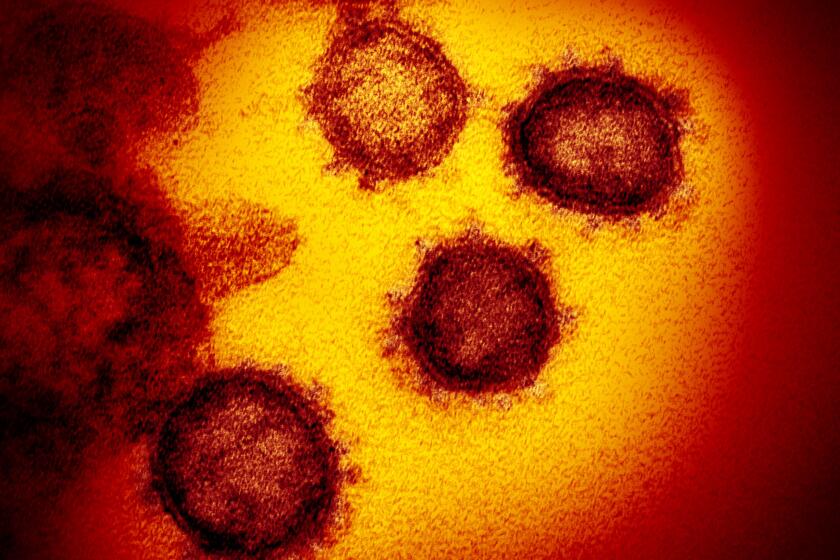

A mutation in the novel coronavirus has led to a new strain viewed as more contagious than the virus that emerged from China, according to a new study.

The 45th president pays little heed to the prattling about American decline internationally even though his signature red ball-cap reads “Make America Great Again.” His vision for America is for less rather than greater international involvement and, by extension, less rather than greater American leadership. To him, less is more — more freedom from international obligation, more ability for America to go its own way, more license to walk the streets without a mask or enter commercial spaces without restraint, and above all more support from a political base suspicious, if not contemptuous, of globalization.

At the same time, however, there are theorists at home who are skeptical of the entire notion of American decline.

Writing in Foreign Affairs, the journal of the uber-establishment Council of Foreign Relations, Morgan Stanley Investment Management chief global strategist Ruchir Sharma expresses doubt that the country is in eclipse after all, especially in economics. “During the 2010s,” he argues, “the United States not only staged a comeback as an economic superpower but reached new heights as a financial empire, driven by its relatively young population, its open door to immigration, and investment pouring into Silicon Valley.”

The United States, moreover, is a remarkably resilient nation with an economic and social culture capable of rally and rehabilitation. Though Jimmy Carter never used the word “malaise” in his 1979 “crisis of confidence” speech, the country was in a funk; its spirit, and then its economy, recovered in the Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton years, and it is arguable that the Persian Gulf War, under George H.W. Bush, revitalized the esprit of the nation’s military after the Vietnam debacle. A decade ago the U.S., still suffering from the effects of the Great Recession, accounted for 42% of global stock market capitalization. By last year that figure had risen to 56%.

Even so, it is unsettling that some of the greatest doubts about the United States in the era of the coronavirus come not from Vladimir Putin’s Russia (once a rival for great-power status) nor from Xi Jinping’s China (now a legitimate economic and perhaps even military rival).

Instead, the gravest doubts come from Ireland, with its sentimental attachment to America growing out of the flood that in some years accounted for half the emigres to the U.S., and from Canada, which in ordinary times sends a quarter of a million travelers a day across its southern border.

The most astonishing reexamination of contemporary U.S. leadership may be occurring in Canada, which has depended on American military protection since FDR extended the American security umbrella to Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King in a stirring 1938 joint appearance in Kingston, Ontario.

Mackenzie King spoke of the bridge the two leaders dedicated that August day as a “monument of international cooperation and goodwill.” But Kinsman, who was Canadian ambassador to Moscow, Rome and the European Union, now is arguing that his country should no longer shelter in place diplomatically, and Sergio Marchi, who was Canada’s ambassador to the World Trade Organization and United Nations agencies in Geneva, believes the U.S. is “now looking tired and uncertain,” arguing:

“Their politics is a mess, and their global leadership is in serious jeopardy. And that was before the coronavirus pandemic. If Trump is reelected, there’s little room for renewal, which has been a long-standing hallmark of Americans society.... Conversely, with a Democrat in the White House, can the situation be salvaged?”

He, and many other Canadians, now doubts that it can, and he urges: “I believe it would be prudent for the Canadian government to weigh the continued decline of the U.S. as a real option, and what this would mean for our national and global issues.”

Power vacuums such as the one some American allies fear have been rare in global history.

Spain’s 17th century eclipse came amid domestic and colonial revolts, deficit spending, population decline and growing dependence upon imported grain, producing a power vacuum that persisted until after the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia. Then it looked as if the French under Louis XIV would fill the gap, but Britain and its broadening empire intervened for more than two centuries, followed by the United States after World War II.

It may simply be that, as former U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson said of Britain in 1962, the contemporary United States has lost an empire — or at least an imperial profile — but has not yet found a role. The coronavirus crisis has laid that bare, and the world awaits America’s response.

Shribman is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.