Europe’s race to develop coronavirus tracing apps runs into privacy roadblocks

LONDON — Goodbye, lockdown. Hello, smartphone.

The race by governments to develop mobile tracing apps to help contain infections after coronavirus lockdowns ease is focusing attention on privacy. The debate is especially urgent in Europe, which has been one of the hardest-hit regions in the world, with nearly 140,000 people killed by COVID-19.

The use of monitoring technology, however, may evoke bitter memories of massive surveillance by totalitarian authorities in much of the continent.

Silicon Valley can come up with apps that might free Americans from home confinement. But Washington fears creating an invasive surveillance system.

The European Union has in recent years led the way globally in protecting people’s digital privacy, introducing strict laws for tech companies and websites that collect personal information. Academics and civil-liberties advocates are now pushing for greater personal data protection in the new apps as well.

Here’s a look at the issues.

Why an app?

European authorities, under pressure to ease lockdown restrictions in place for months in some countries, want to make sure infections don’t rise once confinements end. One method is to trace whom infected people come into contact with and inform them of potential exposure so they can self-isolate. Traditional methods involving in-person interviews of patients are time consuming and labor intensive, so countries want an automated solution in the form of smartphone contact-tracing apps. But there are fears that new tech tracking tools are a gateway to expanded surveillance.

European standards

Intrusive digital tools employed by Asian governments that successfully contained their virus outbreaks won’t withstand scrutiny in Europe. Residents of the 27-nation European Union cherish their privacy rights, so compulsory apps such as South Korea’s, which alerts authorities if users leave their home, or location-tracking wristbands, such as those used in Hong Kong, just won’t fly.

The contact-tracing solution gaining the most attention involves using low-energy Bluetooth signals on mobile phones to anonymously track users who come into extended contact with each other. Officials in Western democracies say that use of the apps must be voluntary.

TraceTogether’s app launch comes as concerns over privacy and intrusive surveillance are rising as governments try to curb the pandemic.

Rival designs

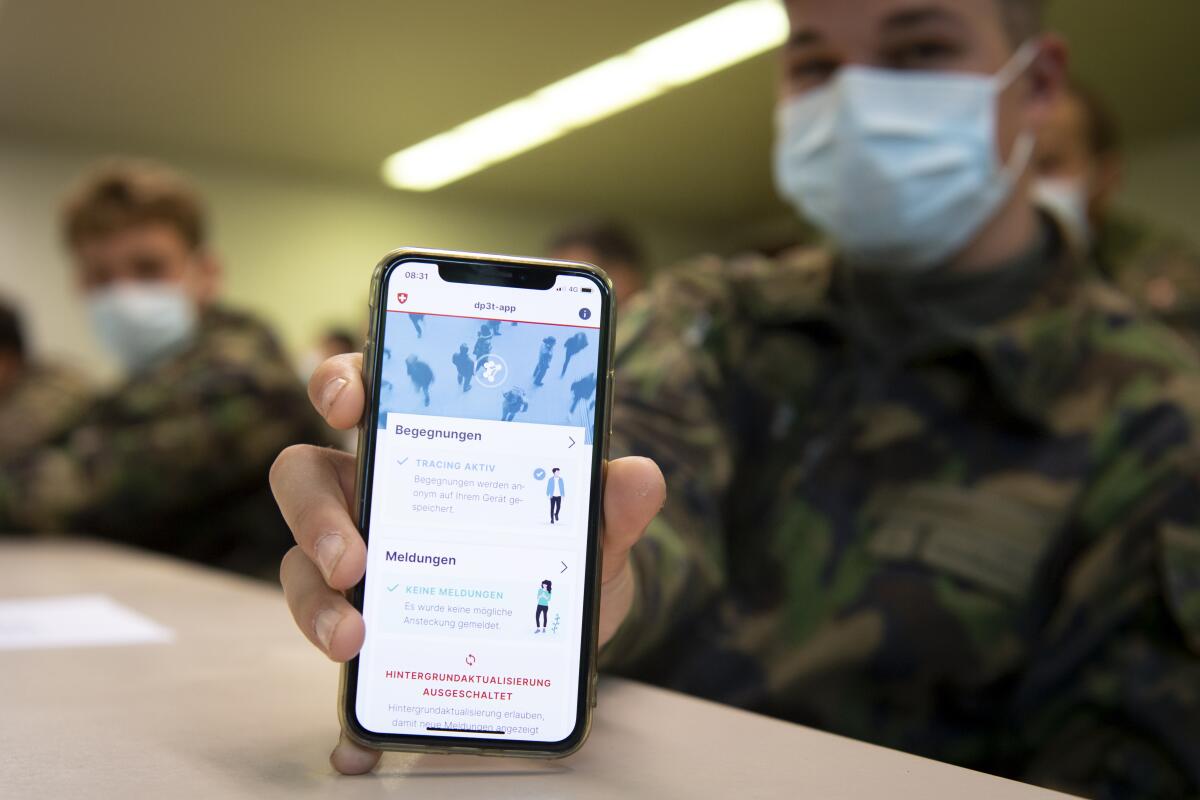

The battle in Europe has centered on competing systems for Bluetooth apps. One German-led project, Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing, or PEPP-PT, which received early backing from 130 researchers, involves data uploaded to a central server. However, some academics grew concerned about the project’s risks and threw their support behind a competing Swiss-led project, Decentralized Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing, or DP3T.

Privacy advocates support a decentralized system because anonymous data are kept only on devices. Some governments are backing the centralized model because it could provide more data to aid decision-making, but nearly 600 scientists from more than two dozen countries have signed an open letter warning that this could, “via mission creep, result in systems which would allow unprecedented surveillance of society at large.”

Apple and Google waded into the fray by backing the decentralized approach as they unveiled a joint effort to develop virus-fighting digital tools. The tech giants are releasing a software interface so public health agencies can integrate their apps with iPhone and Android operating systems, and plan to release their own apps later.

The EU’s executive Commission warned that a fragmented approach to tracing apps was hurting the fight against the virus and called for coordination as it unveiled a digital “toolbox” for member countries to build their apps with.

Here’s why many public health experts are skeptical of contact-tracing tools Apple and Google are rushing to develop.

Beyond borders

The approach Europe chooses will have wider implications beyond the practical level of developing tracing apps that work across borders.

“How we do this, what safeguards we put in, what fundamental rights we look very carefully at,” will influence other places, said Michael Veale, a lecturer in digital rights at University College London who’s working on the DP3T project. “Countries do look to Europe, and campaigners look to Europe,” and will expect the continent to take an approach that preserves privacy, he said.

Country by country

European countries have started embracing the decentralized approach, including Austria, Estonia, Switzerland and Ireland. Germany and Italy are also adopting it, changing tack after initially planning to use the centralized model.

But there are notable exceptions, raising the risk that different apps won’t be able to talk to each other when users cross Europe’s borders.

Leading EU member France wants its own centralized system but is in a standoff with Apple over a technical hurdle that prevents its system from being used with iOS. The government’s digital minister wants to roll it out by May 11, but a legislative debate on the app was delayed after scientists and researchers warned of surveillance risks.

Some non EU-members are going their own way. Norway rolled out one of the earliest — and most invasive — apps, Smittestopp, which uses both GPS and Bluetooth to collect data and uploads the data to central servers every hour.

Britain rejected the system that Apple and Google are developing because it would take too long, said Matthew Gould, CEO of the National Health Service’s digital unit overseeing its development. The British app is weeks away from being “technically ready” for deployment, he told a Parliamentary committee.

Later versions of the app would let users upload an anonymized list of people they’ve been in contact with and their location data, to help draw a “social graph” of how the virus spreads through contact, Gould said.

Those comments set off alarm bells among British scientists and researchers, who warned last week in an open letter against going too far by creating a data collection tool. “With access to the social graph, a bad actor (state, private sector, or hacker) could spy on citizens’ real-world activities,” they wrote.

Despite announcing plans to back European initiatives or develop its own app, Spain’s intricate plan for rolling back one of the world’s strictest confinements doesn’t include a tracing app at all. The health minister said the country would use apps when they are ready but only if they “provide value added” and not simply because other countries are using them.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.