Coronavirus aftermath: Wuhan farmers struggle as crops wither from travel limits

HUANGPI, China — Stuck in the same bind as many other Chinese farmers whose crops are rotting in their fields, Jiang Yuewu is preparing to throw out a 500-ton harvest of lotus root because anti-coronavirus controls are preventing traders from getting to his farm near Wuhan, where the global pandemic started.

Chinese leaders are eager to revive the economy, but the bleak situation in Huangpi, on Wuhan’s outskirts, highlights the damage to farmers struggling to stay afloat after the country shut down for two months.

Authorities are easing travel controls after declaring victory over the virus, but flowers and some other crops deemed nonessential are withering while farmers wait for permission to move them to market.

Most transportation in and around Wuhan, a city of 11 million people in central China’s Hubei province, was suspended Jan. 23 to fight the coronavirus. Trucks carrying food supplies deemed essential were allowed through.

Jiang’s lotus roots, a starchy, popular ingredient in Chinese cooking, and some other crops were not included.

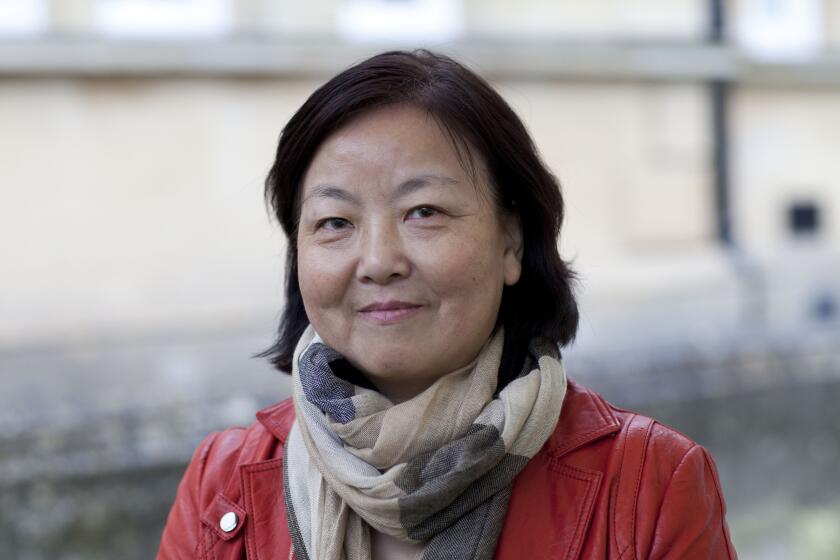

Fang Fang, a novelist from Wuhan, has written an online diary every day under lockdown since Jan. 25. Millions of Chinese readers wait for her updates every night, hungry for an honest voice. Some of her entries are censored by the morning.

“Vendors wanted to come and buy lotus roots but couldn’t make it,” said Jiang, 57, dressed in blue overalls and knee-high rubber boots. “If we don’t do our best, in the second half of the year, we will barely survive.”

The final restrictions on residents of Wuhan leaving the city are due to be lifted Wednesday, but farmers and companies still are working to restore supply chains that carry food to crowded cities and raw materials to factories.

The official China News Service reported that Hubei will create “green channels” to get production supplies to farmers and crops to market. Jiang and his neighbors in this area about 20 miles northeast of Wuhan’s city center said they still were waiting for clearance.

Guo Changqi, who grows flowers for sale in Wuhan, said officials visited to ask vegetable farmers about their losses. Not him.

Guo said he has thrown away more than 20,000 pots of flowers, which usually sell for 70 to 85 cents each at his stall in a wholesale market in Wuhan. The market has reopened, but there are few customers, he said.

“We live on flowers,” said Guo, dressed in a wide-brimmed straw hat as he walked past rows of pots of dead flowers. “If we have no way to sell them, life will get harder.”

Farmers are hoping for government help.

“We can do nothing about the epidemic,” said Jiang. “If the government could find a way to sell lotus roots, it could minimize our losses, but so far they haven’t done anything.”

The lotus roots grow under knee-deep water in Jiang’s 20 football-field-size ponds. Traders who supply markets as far away as Shenzhen, adjacent to Hong Kong in the southeast, usually pay about 12 to 14 cents per pound.

China’s multibillion-dollar wildlife industry is driven by corporate interests and traditional Chinese medicine companies whose animal-based remedies are prescribed as treatment for the coronavirus.

Some farmers are finding temporary outlets for sales through volunteers in Wuhan helping the elderly and other vulnerable people get food supplies. They buy directly from farmers and arrange delivery to apartment complexes.

Online grocery orders surged in Wuhan and other cities after families were ordered to stay home. The government also arranged food deliveries. But some residents had no access to websites and smartphone apps.

“Especially for empty-nesters, they didn’t know how to buy food from this channel even though they had money,” said volunteer Luo Hao.

Jiang’s neighbor Dong Yumei, who raises cabbages, said her sales have fallen by 80%. Most of her business now is with the volunteer network in Wuhan.

“The farmers here are so nice and the vegetables are cheaper,” said Luo. “They’re also fresh from the farm.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.