Coronavirus has led to thousands of early releases from prisons and jails. Not in Arizona

KINGMAN, Ariz. — As more U.S. states issued orders granting early release to thousands of older, nonviolent inmates at risk for contracting the coronavirus, Arizona’s governor balked.

Not here, said Gov. Doug Ducey, claiming less drastic health measures were enough.

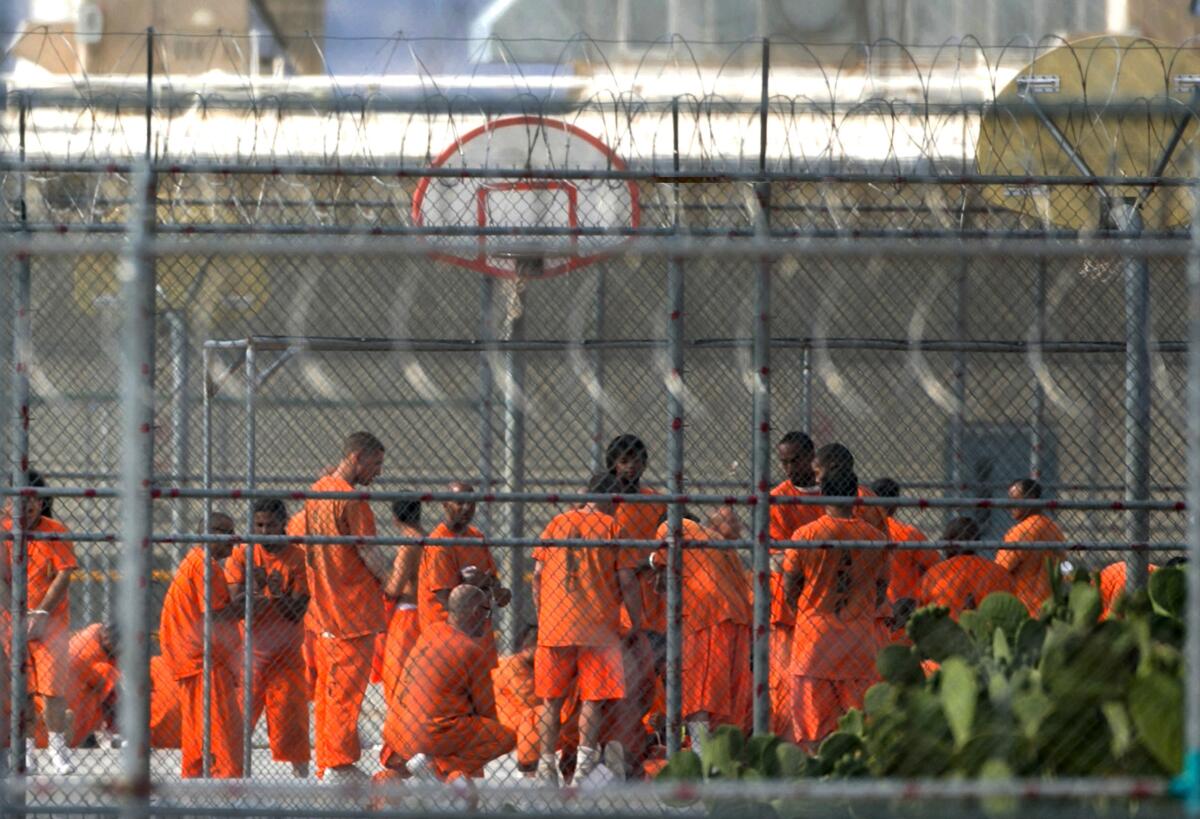

With more than 42,000 inmates, Arizona has the highest incarceration rate in the western United States and the fifth-highest in the nation. As cases of COVID-19 soar in the nation’s cramped, overcrowded prisons, the state is among several facing intense criticism for what civil rights groups, families of prisoners and corrections officers say is a haphazard response.

In California, officials have weighed plans to potentially release thousands of prisoners months ahead of their scheduled release dates. In Kentucky, the governor said he will commute more than 900 sentences for non-violent offenders. New Jersey is releasing at least 1,000 people from county jails, while in Ohio, the jail population has been cut in half. Federal prisons are also looking at speeding up the release of high-risk inmates.

Elsewhere, the response has varied. In Texas, activists protested an order by Gov. Greg Abbott that makes people convicted of violent crimes post bail before release, a move that has hampered local efforts at decarceration as the virus spreads. In Florida and Wisconsin, corrections departments will no longer admit inmates, but advocates say the move only further shifts the public health crisis to crowded local jails. The same goes for Arizona, where prisons won’t take in new inmates for at least much of April.

Meanwhile, the number of COVID-19 cases in the more than 1,700 state and 100 federal prisons and thousands of jails has climbed by the hundreds. In the last week, prisoners in Louisiana, Missouri and Illinois have died from COVID-19.

In Arizona, families of prisoners, advocates and corrections officers have complained of the state’s response.

After a Phoenix-area corrections officer filed a whistleblower complaint saying the state banned guards from wearing masks, Arizona reversed course, saying prison workers would make masks for use among all personnel. Prisoners have made 8,000 so far; each guard will receive two.

Amid accusations from the American Civil Liberties Union that it lacked an adequate plan to address the pandemic, a federal judge recently ordered the Arizona Department of Corrections to issue regular reports on testing results for the coronavirus.

The judge cited the state’s “failure to accept what may be a grave threat” facing prisoners.

“The most effective way to reduce the spread of COVID-19 in prisons is to reduce the population,” said Rubén Lucio of the ACLU of Arizona. “The governor is playing a dangerous game with human lives by refusing to release people. On top of that ... people are still having trouble getting soap, medical care, protective equipment and basic information about COVID-19.”

A spokesman for the Arizona governor did not reply to an interview request from The Times.

This week, two Arizona prisoners tested positive for the coronavirus. But only 60 have gotten tested since the first batch was announced on March 23, after the federal court forced the state to come up with a plan to address the virus in prisons.

The department has not released testing data on corrections officers. Corrections guidelines now require guards to undergo an “infectious disease symptoms check” before entering prisons. Those with flu-like symptoms are sent home.

Overall, the state has more than 2,500 coronavirus cases that have led to 73 deaths.

Those with family members in prison say the testing is too late, with numbers that sound too good to be true.

At the state prison on the edge of Kingman, a city of 28,000 near the California border in the high desert, there have been no reports of infections among the 3,508 inmates.

Still, Deborah Jordan, whose husband, Bill, has been incarcerated at the minimum-security facility since 2017, spends most days waiting by the phone, hoping for good news.

After suspending visits, officials now allow inmates two free 15-minute phone calls each week; they used to get one. Soap is now free, and the usual $4 medical payments for prisoners with flu and cold symptoms are canceled.

“All of this is numbing,” said Jordan, who lives in Tucson. “The state needs to be on the front lines and making sure this virus does not get inside.”

Her 78-year-old husband, who has diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, is at a higher risk to die from the virus if he contracts it. He’s eligible for release next year after serving time for a nonviolent sex offense.

Each day, inmates with health issues report for “pill calls,” Jordan said. “On any given day during these calls, 50 or so men, with no masks, huddle inside a room to get medication. There is no social distancing.”

Her husband told her that corrections officers only recently started wearing masks.

“That offers some relief, but they should have been wearing masks weeks ago,” she said. “When the virus does get inside the prison, it’s going to be from the outside.”

Sue Gillmore, a Rexburg, Idaho, resident whose son Daniel is at Arizona’s Douglas Prison, in Cochise County near the border with Mexico, said she often asks him about sanitation on their twice-weekly calls. He has four more years of a 12-year sentence to serve for a conviction on drug and weapon possession.

“Inmates who are ‘hired’ by [the Department of Corrections] to do the cleaning at the facility every two hours are paid 20 cents/hour and are given some cleaning supplies,” Gillmore wrote in an email, relaying what Daniel told her on a recent call. “They are assigned specific areas to clean but are not supervised and the work is not checked. These inmates may or may not be doing their jobs.”

Now more than ever, activists say, prison sanitation and overcrowding is a life-or-death issue, in particular for black and Latino men, who are incarcerated at disproportionately high rates in many states. Activists also say that money saved from decarceration could be funneled toward public health measures for people who are not imprisoned.

According to a recent report by the New York-based Brennan Center for Justice, nearly 40% of inmates are incarcerated for nonviolent offenses, mostly related to drugs. Releasing them, the report found, would save $20 billion a year.

“If prisons are like cruise ships — worse, even, because they’re overcrowded and unsanitary — then governors’ responses suggest they are willing to tolerate on their watch the virus infecting those in the prisons and the correctional officers who work in them,” said Rob Smith, executive director of the Justice Collaborative, an advocacy group that supports decarceration.

He said that would inevitably pose dangers far beyond the confines of the prisons, with the coronavirus “then crashing into their communities.”

Vincent Schiraldi, co-director of the Columbia University Justice Lab, said the U.S. faces unique challenges with the coronavirus in prisons, since the country’s incarceration rate is higher than others where there have been outbreaks.

“We incarcerate five and six times as many people per capita as China and Italy, respectively,” Schiraldi said. “People in prison are medically vulnerable.... They suffer from ‘poverty illnesses’ like asthma, heart disease and diabetes more frequently, and incarceration healthcare is often sub-standard.”

Schiraldi added, “If one were inventing an environment to deliberately increase contagion or foment community spread … one could hardly do better than mass incarceration.”

Lee reported from Kingman, Ariz., and Kaleem from Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.