HONG KONG — Slap, slap, slap.

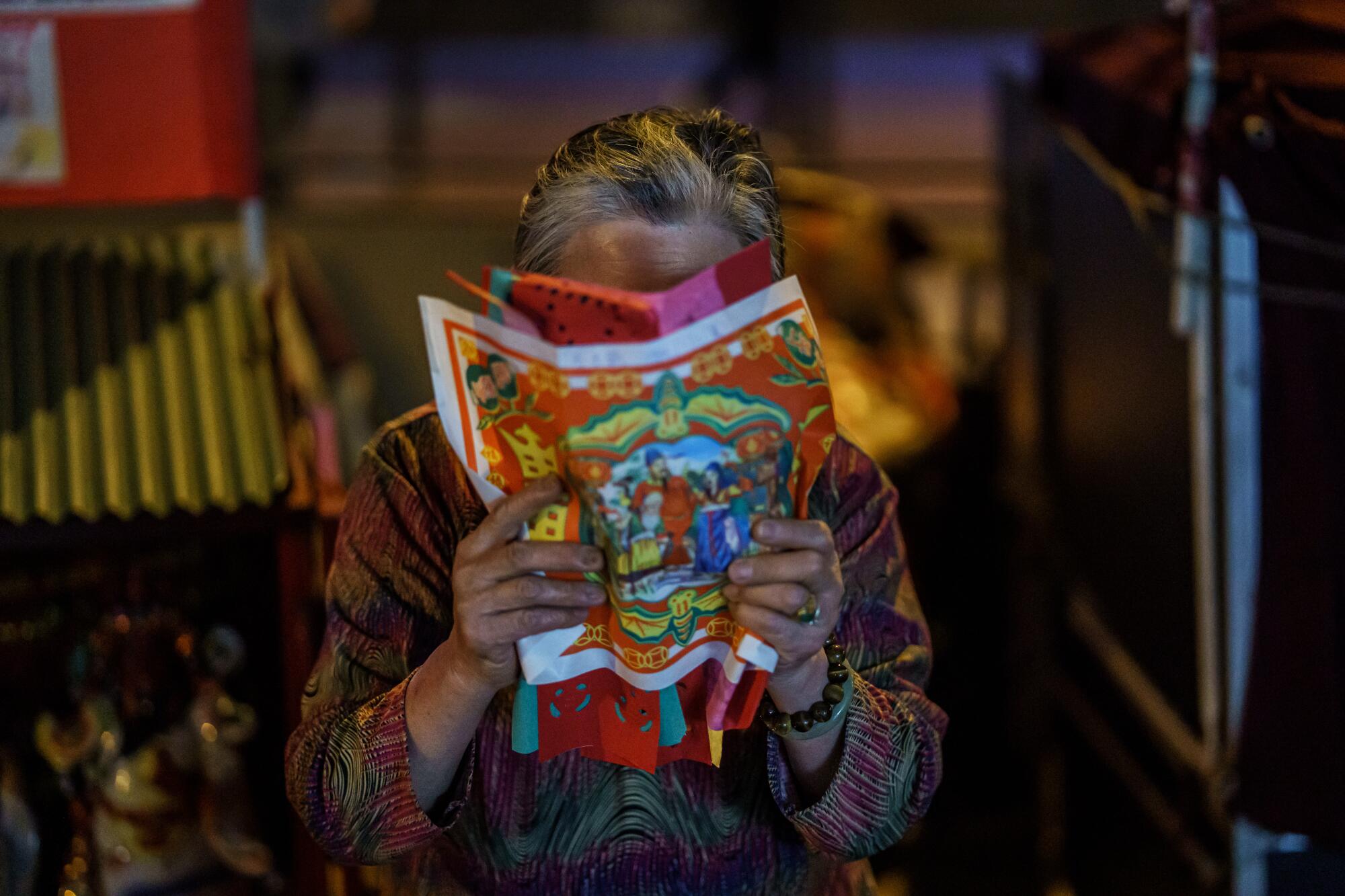

The sound echoed off a highway bridge overhead, cutting through the beeping and ringing of car horns and crosswalk bells. Under the bridge, a wrinkled woman in a red vest and flowery shirt hunched over on a stool, pressing a paper figurine down on a stack of bricks with one hand, raising an old slipper to the sky with the other.

She paused, taking aim at the paper person, then bashed the shoe down like a chef with a cleaver, chopping and chanting in Cantonese. Slap, slap, slap-slap-slap.

“Beat your little hand, beat your little eye, beat your little foot, beat your little mouth,” she muttered, smashing the “small person,” a Chinese phrase meaning one who’s petty, villainous or otherwise a “bad guy.”

She scribbled invisible words on a yellow scroll with an incense stick, murmuring another spell, then passed it to the customer.

“Keep this with you,” she said. “You’ll be safe from the coronavirus.”

Grandma Leung, 85, was one of half a dozen women practicing an ancient Cantonese ritual called “villain hitting” — native to the agricultural regions of southern China, where farmers once prayed to protect their villages from tigers in the wild — in the middle of a bustling business district in Hong Kong.

Like the rest of the women, she asked to be referred to by her work title rather than her full name.

For less than $7, Grandma Leung could curse one’s enemies, whether abstract ones like bad luck and unemployment, or specific ones like a boss, co-worker or ex-boyfriend. She summons spells to break negative influences and provides an immediate, almost cleansing satisfaction by beating a paper version of one’s nemesis to tatters.

Grandma Leung and the other women each sat in front of a different shrine, incense wafting around the Chinese god and goddess statuettes before whom they placed offerings of pomelos and mandarin oranges. Leung took a paper tiger, rubbed it on a piece of raw pork and set it on fire, waving the flaming animal around a customer’s head.

The tiger is a symbol of any potential misfortune, she explained. Feeding it pork makes its too full to feed on humans. Setting it on fire helps to scare away ghosts.

Just before it burned her hands, she tossed the blazing feline into a bin.

Like many Chinese religious rituals, “villain hitting” is a mix of Buddhism, Taoism, ancestor worship and folk traditions. It’s hard to explain but easy to access, wrapped into a pragmatic, convenient stop for passersby who may not understand its mysteries, but find it prudent to purchase a curse and beating or two, just in case.

In mainland China, many such practices were outlawed during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and ‘70s, condemned as superstitious rites that held the communist nation back from science and progress. Rural magicians in Guangdong province went underground, quietly tapping the “small persons” they wanted to curse and hiding their spells from Communist Party cadres.

Chinese traditions were ironically better protected in Hong Kong, a British colony at the time and now a special administrative region with protected rights including freedom of speech, religion and assembly under a separate legal system from mainland China’s.

“Villain hitting” has been listed in a government inventory of “intangible cultural heritage” to be protected in Hong Kong, alongside Cantonese opera, dragon dances and herbal tea.

In Guangdong, farmers traditionally beat villains and made offerings to paper tigers on a day on the solar calendar called jingzhe, “insects awakening,” when animals rise from hibernation as winter turns toward spring. That was March 5 this year.

Tens of thousands of customers usually visit the bridge shrines on jingzhe, said Auntie Yung, 58, another villain-hitting practitioner.

But only a few thousand came this year, afraid of leaving their homes because of the novel coronavirus. Their requests were overwhelmingly for fending off unemployment and bad health, she said — the tigers and villains facing Hong Kong today.

Hong Kong has been through an extraordinary year of unrest, rocked by mass anti-government protests against police violence and Beijing’s growing control over the territory. The tension has been compounded by economic downturn in a city that is already one of the most financially unequal metropolises in the world, and now facing the COVID-19 pandemic.

Good luck, and the catharsis of watching your enemies beaten, is in demand.

On a recent afternoon, at least a dozen customers visited the women within an hour, many of them asking for a spell to cast away misfortune because they or their children were born in the year of the rabbit, according to the Chinese zodiac, which makes this year unlucky for them.

Others sought spells to ward off the coronavirus, an additional precaution to the surgical masks and hand sanitizers already fastened to their faces and bags.

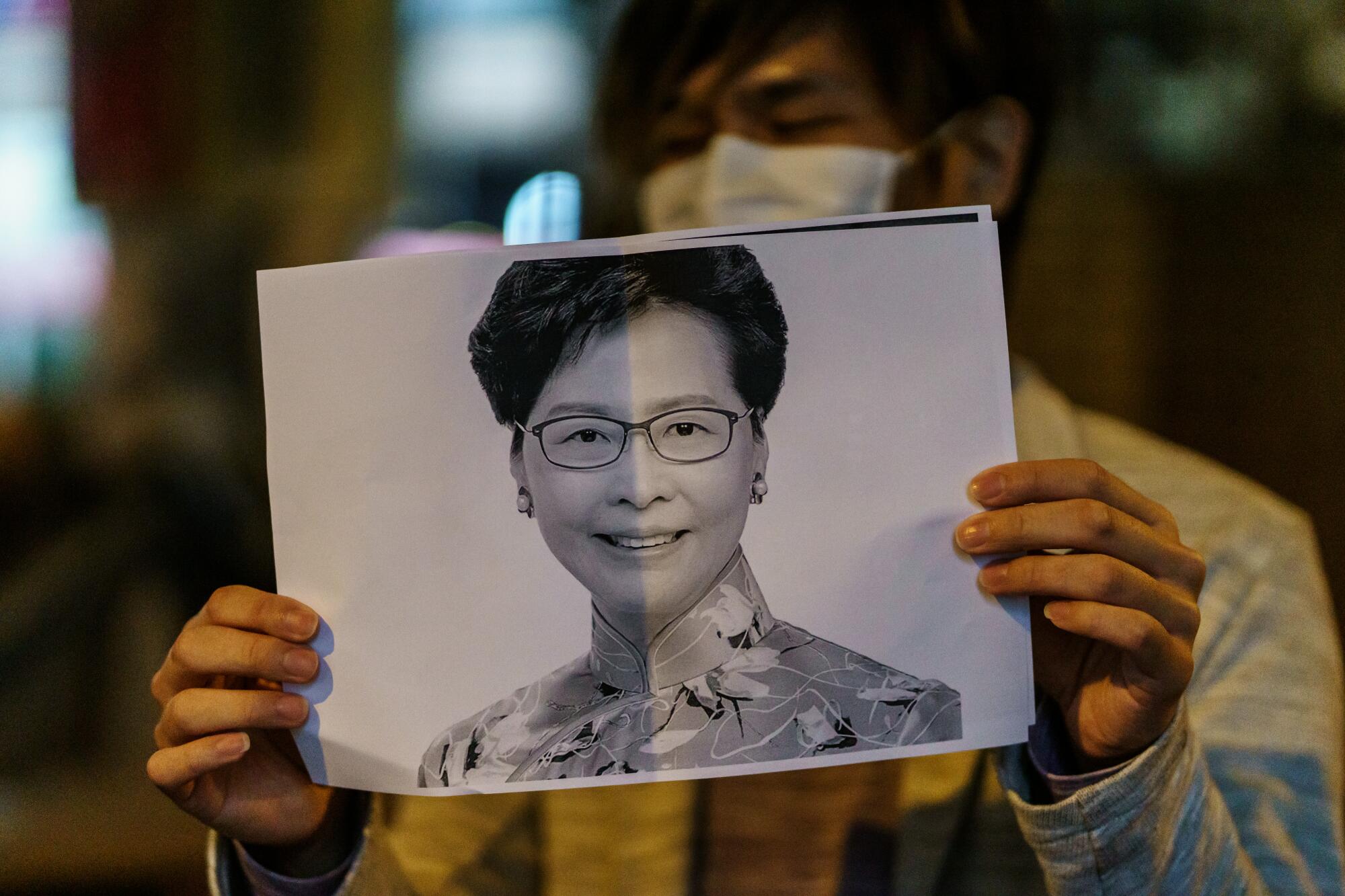

And at dusk, just as the rush of people getting off work began to swirl around the shrines, a young woman and man approached Grandma Leung with two rolled-up photos. They unfurled them, revealing the faces of Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam and police commissioner Chris Tang.

Leung shook her head.

“She thinks they’re good people,” said the young woman, who gave only her surname, Cheung, to shield her identity from authorities, as she walked away in disappointment. “Obviously, we think they’re very bad.”

Cheung, who does administrative work in the legal industry, said she and her friend were among many Hong Kong protesters angry at the government and police for excessive use of force and “suppressing freedom of speech through arbitrary arrests.” Protests have died down somewhat as most Hong Kongers avoid public gatherings to prevent spread of the coronavirus.

“But people are still really angry,” she said. “It’s not the end, just a pause.”

As for whether beating photos of political figures could change the situation, Cheung shrugged. “Maybe it just makes ourselves feel better,” she said. “But hopefully it works.”

The business of coaxing spells is not as good since Hong Kong’s protests began, Leung said. Many of the marches took place near her shrine, and few came to see her when police were firing rubber bullets and tear gas and protesters throwing bricks and Molotov cocktails.

Leung said she wouldn’t beat paper figures of any government officials or politicians, despite getting many requests. Several of the other women agreed that they refused political requests, which have included triads, protesters, police, political leaders in Hong Kong and China, and President Trump.

A few of the villain-hitting women told fantastical stories about why they practice their craft. Auntie Yung, who came to Hong Kong after marrying a local man more than 20 years ago, said she learned fortune-telling and villain-hitting from a master in Guangxi province.

As a teenager, she’d apprenticed with a master after she claimed he healed her from a kidney infection that hospitals couldn’t treat — by having her drink the ashes of a burnt paper spell mixed with water.

Others were more practical. Grandma Leung said she moved to Hong Kong from Dongguan, in Guangdong province, in 1983. She’d lost all her family, she said, and came alone to work as a housekeeper. She lost that job after a wrist injury, and began selling cardboard she scavenged on the streets for recycling.

One day, she passed this bridge and someone asked her if she was interested in villain-hitting. “So I started this career,” Leung said. “I’ll work until I can’t move.”

Did she believe the magic actually worked? Leung thought for a moment.

“Sometimes it doesn’t,” she admitted. “But most of the time, it does.”

Special correspondent Antonia Tang contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.