South Korea’s rapid coronavirus testing, far ahead of the U.S., could be saving lives

SEOUL — In mid-February, as a surprise snowstorm swept across the Korean peninsula and the country basked in the afterglow of “Parasite’s” Oscar win, South Korea’s coronavirus spread was looking manageable.

The country had about 30 infections, largely from known contact with travelers from China. None had died. South Korean President Moon Jae-in — as it turns out, quite prematurely — told a group of business leaders the threat from the virus would be over “before long.”

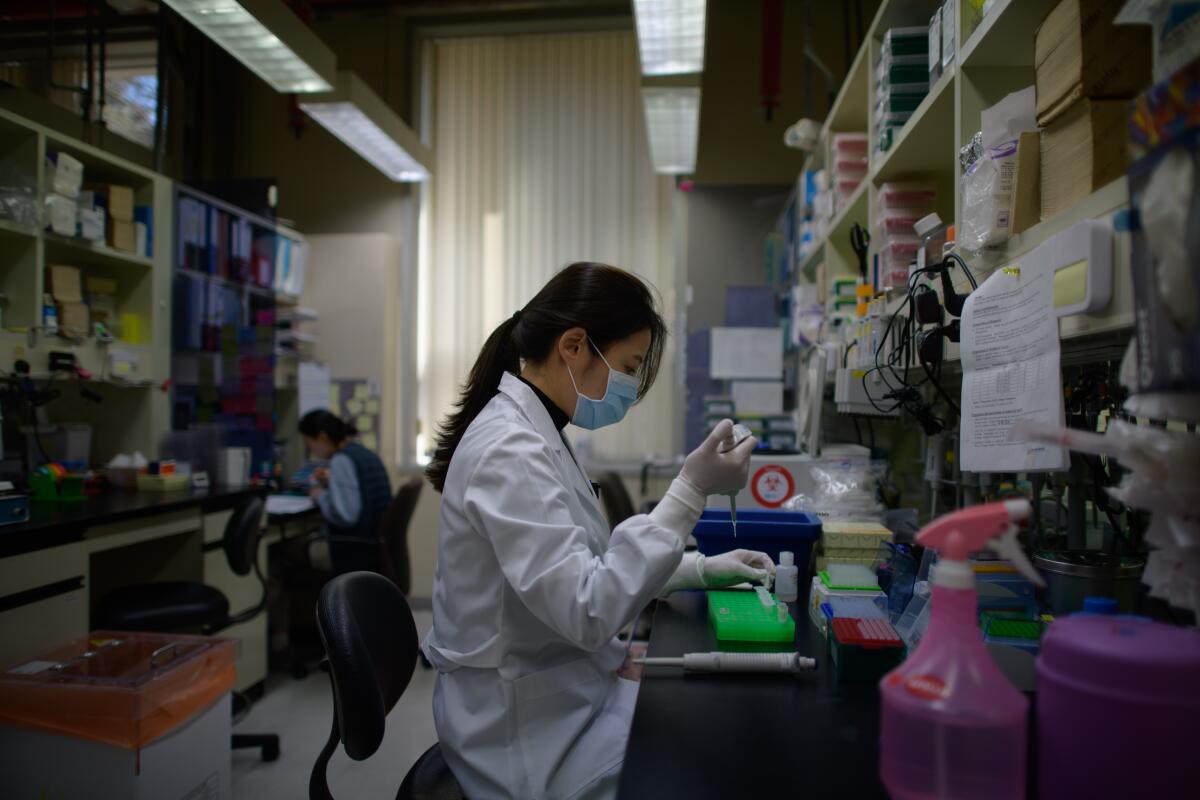

All the while, behind the scenes, a network of laboratories was quietly ramping up capacity for the possibility of widespread transmission. They were ready.

In the first weeks of February, the country had tested nearly 10,000 patients for the novel coronavirus — the vast majority of them getting the all-clear — in an effort to detect as many cases as possible.

In the weeks since, South Korea has been on average testing 12,000 patients a day — about as many as the U.S. has managed to test over the last two weeks.

Authorities here have collected samples at 50 drive-through clinics across the country. A South Korean innovation that’s sprung up in Germany, the U.K. and Australia and has also been embraced by President Trump, the set-up allows drivers to remain in their cars as they answer a brief questionnaire, have their temperature taken and get swabbed inside the nose. It takes about 10 minutes, compared with the hour or so walk-in clinics can take, while minimizing exposure to health workers and other patients in waiting rooms.

South Korea has also set up mobile testing stations and home visits, and can conclude in a matter of hours whether someone has been infected. Even as the ranks of the infected swelled by several thousand, the aggressive testing has given health officials here the ability to spot outbreaks as they emerge, focus resources on those areas and isolate those with the potential to spread the virus.

“The enormous testing capability allows us to identify patients early and minimize the harmful effects,” Vice Minister of Health and Welfare Kim Ganglip told reporters this week. “This is the most important means of fending off a contagious disease outbreak.”

As of Saturday, South Korea had confirmed more than 8,000 coronavirus patients and 72 deaths — after having tested more than 240,000 in about a month and a half. The early detection, isolation and treatment has translated into a low mortality rate of about 0.7%, compared with more than 3% worldwide.

In the U.S., with six times the population of South Korea, about 2,000 infections had been reported and 43 have died as of Friday. But even more concerning is what’s unknown. With the limited availability of testing, doctors and public health officials are having to pick and choose whom to test — raising concern about the untold others unknowingly spreading the deadly virus.

“The system is not really geared to what we need right now,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said of the U.S.’s testing capabilities at a hearing before the House Oversight and Reform Committee this week. “That is a failing. Let’s admit it.”

How South Korea accelerated its coronavirus testing, while early missteps left the U.S. lagging far behind, is a story of flexibility, preparedness and painful lessons from a past fumble.

Much of South Korea’s current disease control response system was forged after a 2015 local outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome, or MERS, caused by a different coronavirus. At the time, the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found itself unable to handle the abrupt surge in demand for tens of thousands of tests amid the largest outbreak outside of Saudi Arabia, which ultimately killed 38 patients and infected nearly 200.

The experience prompted the country to overhaul its CDC and pass laws to prepare for the next epidemic. Central to the changes was the ability to cut through a bureaucratic months-long process to get test kits rapidly approved and working during an emergency. The Zika virus epidemic of 2016 served as a small-scale dry run of the new system.

As luck would have it, last December, the South Korean government held a mock disease response drill — under the premise of a coronavirus outbreak.

By Jan. 11, when China had reported just 41 cases and the WHO was discounting the prospect of human-to-human transmission, South Korea was distributing tests even though it wasn’t yet possible to test for the specific strand of the novel coronavirus causing the outbreak in Wuhan. By Jan. 31, with seven known cases in South Korea, test kits based on the virus’ genetic code released by China had been distributed to local government labs across the country.

By the time authorities discovered a large cluster of thousands of infections in the southeastern city of Daegu in late February, the network of public health institutions and private labs and hospitals was prepared.

Early on, officials dropped the requirement that patients had to have traveled abroad in order to be tested, a criteria that has been an impediment to testing in America. When it became clear many of those who had attended the services of an obscure religious sect had been infected, authorities tested all of those with symptoms among the church’s more than 200,000 members. When outbreaks developed at a psych ward and at a call center, authorities called for a nationwide survey of all locked psych wards and all call centers. Officials also began screening all pneumonia patients with no known causes for the novel coronavirus.

Hong Ki-ho, director of laboratory medicine at Seoul Medical Center, who is also a member of the COVID-19 task force at the Korean Society of Laboratory Medicine, said Korea’s CDC, private labs and manufacturers had all contributed to the unprecedented scale-up of testing.

“It feels like a miracle that it all came together like this,” he said, noting the chaos and confusion the delays in testing caused during the MERS outbreak. “It’s so many times the scale of what it was during MERS, and we had so little time to prepare.”

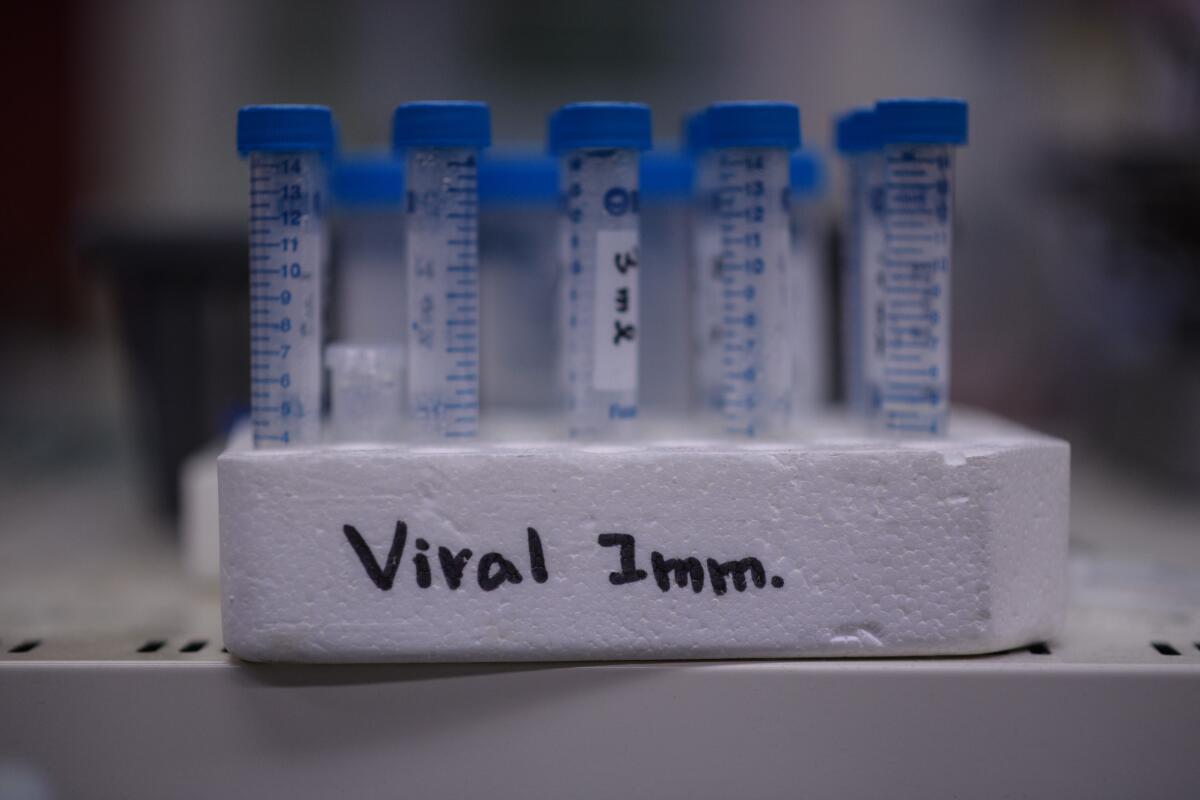

Vials at the International Vaccine Institute in Seoul.

Another key component of South Korea’s response is making tests free for the vast majority of those who have been screened, and covering the cost of their hospitalization and treatment. Even those who request a test without a doctor’s note can do so at the moderate cost of about $130.

After a peak in late February, when the number of infections was jumping by as many as 900 cases a day, the pace of new infections in South Korea has slowed to about 100 new cases reported Saturday. With new clusters being discovered in the densely packed Seoul metropolitan area this week, South Korea still faces challenges.

That hasn’t stopped the country from holding itself out as a model for other nations, highlighting the fact that it appears to be gaining a handle on the outbreak without the drastic travel restrictions China, the U.S. and other countries have imposed on their citizens.

“Public trust can only be earned and harnessed through full openness and transparency,” Lee Tae-ho, vice minister of foreign affairs, told reporters. “This public trust has resulted in a very high level of civic awareness and voluntary cooperation that strengthens our collective effort to overcome this public health emergency.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.