In Mexico, International Women’s Day puts a spotlight on femicide

International Women’s Day on Sunday celebrates the social, political and economic gains of women, yet finding a way to effectively stem, if not end, gender-based killings remains a challenge in many parts of the world.

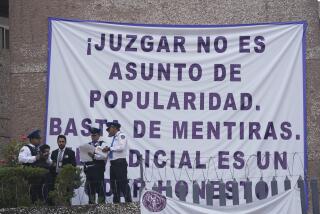

A gruesome case in Mexico last month, in which a man disemboweled his wife and skinned her corpse, generated outrage about how authorities respond to such killings. Activists have called for a national women’s strike Monday — skipping work or school and not purchasing anything for a day — in part to focus attention on what they perceive as a crisis of violence.

Activists are particularly enraged about a rise in femicide, a term used to describe certain kinds of homicides targeting women. Amid the outcry, Mexican lawmakers have proposed a reform that would increase the maximum prison sentence for anyone found guilty of femicide from 60 to 65 years, but the move, according to several legal analysts, at best would be symbolic.

“Increased penalties have never proven to deter crime,” said Cristina Reyes Ortiz, senior attorney and gender specialist at the nonprofit Mexico United Against Crime.

Here is a look at some of the issues and statistics related to gender-based violence against women.

What is femicide?

Merriam-Webster defines femicide as the gender-based slaying of a woman or girl by a man. In practice, there are various interpretations of what the term means, including some jurisdictions that restrict its use to cases in which the perpetrators are intimate partners or family members. Some law enforcement systems do not use the term as a specific category for homicides.

What are some of the statistics related to the killings of women worldwide?

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, the last available data show that 87,000 women were intentionally killed worldwide in 2017. Of those killings, the agency identified 50,000 as femicides.

For country-specific data, the agency refers to a Global Burden of Armed Violence report released in 2015, which lists the 25 countries with the highest rates of female homicides.

El Salvador topped the list with a rate of 14.4 homicides per 100,000 women. Mexico was 23rd on the list, with a rate of about 3.3. The Philippines, with a rate of about 3.1, was 25th. The United States was not included.

What kinds of efforts exist to track the slayings of women and girls?

In its report, the U.N. acknowledges that men make up the bulk of global homicide victims, estimating that they represented 81% of the 464,000 deaths documented in 2017. But a general increase in violence, the agency added, also affects women and girls of all nations, who are subject to different forms of violence because of their gender.

The agency limits its femicide count to cases involving intimate partners and family members, recognizing that doing so renders an incomplete picture of the problem. The report laments the “severe limitations in terms of data availability” that prevent it from tracking other types of gender-based violence, such as female infanticide; the killing of indigenous women and sex workers; and dowry and honor killings.

The U.N. says its report is based on information supplied by national statistical systems in which the relationship between the victim and perpetrator is reported. This framework covers most gender-related killings of women, signaling that the majority of femicides occur at the hands of intimate partners and family members, the agency said.

It excludes victims such as 7-year-old Fátima Cecilia Aldrighetti, who was allegedly abducted by a woman after being dismissed from school last month in Mexico City. After her body was found in a bag just blocks away from her home, an autopsy revealed that she’d been beaten and sexually abused. A woman and a man not related to her have been charged in connection with Fátima’s death.

Likewise, a focus on cases in which perpetrators are intimate partners or family members leaves out Ruth George, a student in Chicago who was sexually assaulted and killed after ignoring a catcaller in November.

In the United States, the Violence Policy Center publishes an annual report on female homicide victims based on FBI data. Like the U.N., that report focuses on cases involving family members and intimate partners.

What are some of the differences among nations with femicide laws?

In 2007, Costa Rica became one of the first nations to pass anti-femicide legislation, making the crime punishable by up to 35 years in prison. This law, which focuses on married couples, also asks authorities to consider whether the victim had sensory, physical or mental disabilities; was pregnant or had recently given birth; or was more than 65 years old.

Peru, which put femicide on the books by amending its penal code in 2011, made the crime punishable by 15 to 25 years and also focuses on intimate partners and family members.

Mexico listed femicide as a penal category in 2012. In addition to determining whether there was an “emotional or close relationship” between the victim and the suspect, it considers whether the victim was ever subject to threats, harassment or sexual violence; whether the victim suffered bodily harm or mutilation before or after being killed; and whether the victim’s body was put on display, among other factors. Additionally, public servants found to delay or obstruct investigations into the killings are subject to three to eight years in prison.

What is the trend in gender-based violence in Mexico?

In 2019, Mexico recorded 35,558 homicides, of which 3,825 were female victims. Officials classified 1,006 of those killings as femicides. Officials recently issued a statement signaling that femicides were up 137.5% since 2015.

In an effort to address the country’s violence, corruption and impunity, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s administration is working on a National Penal Code to standardize crime descriptions across its 32 states. Early this year, Atty. Gen. Alejandro Gertz Manero pitched the idea of eliminating femicide as a penal category, but several members of Congress immediately denounced the move, as did Mexico’s National Institute for Women.

According to the institute, eliminating the existing femicide category would represent a severe “setback in matters of securing justice for women and girls.” It also emphasized that “the definition of femicide in Mexico is the product of a social and legal battle [waged by] the feminist movement, civil society organizations and relatives of murdered women for the recognition of one of the most extreme manifestations of violence against women.”

Late last month, Secretary of the Interior Olga Sánchez Cordero met with feminist scholars, lawmakers and civil society groups and said that the federal government would move to address gender-based violence holistically. For instance, given that some authorities wait 72 hours before looking for a missing person, they would be instructed to start searching immediately after a woman or girl was reported missing, she said.

Sánchez Cordero acknowledged the “legitimate demands of different feminist movements,” along with the government’s responsibility to take on femicide.

“We recognize that we’ve come late with this message,” she said.

Times staff writer Kate Linthicum in Mexico City contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.