Islamic State victims see satisfaction but no closure in Baghdadi’s death

PARIS — For Georges Salines, whose 28-year-old daughter Lola was killed when Islamic extremists went on a bloody rampage in Paris in 2015, the death of the man who inspired the attack brought a welcome “sense of satisfaction.”

But like other survivors and families of victims of the militant group Islamic State, Salines stressed that the death of its leader, Abu Bakr Baghdadi, does not mean the fight against terrorism is over.

“It would have been even better if Al-Baghdadi could have been captured and sent to trial,” Salines told the Associated Press. “That was probably impossible. We knew that for a long time.”

Baghdadi was responsible for directing and inspiring attacks by his followers around the world. In Iraq and Syria, he steered his organization into committing acts of brutality on a mass scale: massacres of his opponents; beheadings and stonings that were broadcast to a shocked audience on the internet; and the kidnapping and enslavement of women.

His death was announced Sunday by President Trump, who said Baghdadi detonated an explosives vest while being pursued by U.S. forces in Syria, killing himself and three of his children. It was another major blow to the Islamic State group, which in March was routed by U.S. and Kurdish forces from the last part of its self-declared caliphate that once spanned a swath of Iraq and Syria at its height.

Islamic State claimed responsibility for the Nov. 13, 2015, attacks on Paris cafes, the national stadium and the Bataclan concert hall that left 130 people dead, including Lola Salines and Thomas Duperron, 30.

Duperron’s father, Philippe, who is president of the French victims association 13onze15, which takes its name from the date of the attacks, said Baghdadi’s death was “not bad news.”

“One major player of the Islamic State group’s actions has disappeared,” he told AP, although he said that his group would not express joy at any death.

A trial of suspects in the Paris attacks is expected to begin in 2021. French prosecutors said this month that the judicial investigation of the attacks has ended and that 1,740 plaintiffs have joined the proceedings. Fourteen people have been charged in the case, including Salah Abdeslam, the only surviving suspect of the group of assailants.

French magistrates had recently issued an international arrest warrant for Baghdadi in a counter-terrorism investigation for “heading or organizing a criminal terrorist conspiracy.”

Arthur Denouveaux, a Bataclan survivor and president of the Life for Paris victims group, told the French newspaper Le Parisien that we, “the victims, are not seeking revenge ... but a desire for justice.”

Baghdadi’s death is “symbolically is a major blow to the operational capacities” of Islamic State, he said.

“It is essential to continue the fight for the security of the region and also of European countries,” Denouveaux added.

Islamic State claimed responsibility for three suicide bombings in Brussels on March 22, 2016, that killed 32 people at its airport and in a metro station. Philippe Vansteenkiste, who lost his sister in the airport bombing and went on to become director of V-Europe, an association of victims of those attacks, said he knows the fight is not over.

“This is a new step in the fight against Daesh, but I’m not naive,” Vansteenkiste said, using a derisive Arabic acronym for the militant group. “Their spiritual leader has been hit, but Daesh and many sleeping cells still exist, either in Syria or in our country.”

The parents of Steven Sotloff, an American-Israeli journalist who was killed by Islamic State, thanked Trump and the U.S. forces that conducted the raid that led to Baghdadi’s death.

“While the victory will not bring our beloved son Steven back to us, it is a significant step in the campaign against ISIS,” Shirley Sotloff told reporters at their Florida home, using another acronym for the militant group.

In 2014 and 2015, the militants held more than 20 Western hostages in Syria and tortured many of them. The group beheaded seven U.S., British and Japanese journalists and aid workers and a group of Syrian soldiers. Sotloff was among them.

In Jordan, Safi Kasasbeh, whose son was slain by Islamic State after being captured in 2014, said he was “very happy” to learn of Baghdadi’s death.

“I wished that I killed him with my bare hands,” Kasasbeh said. “This was one of my dreams, if not to be the one who kills him, at least to witness the moment when he gets killed. But Allah didn’t want that to happen.”

Moaz Kasasbeh was a fighter pilot who was captured by Islamic State militants after being shot down while fighting in a U.S.-led coalition in Syria. The militants locked him in a cage and burned him to death, and later broadcast video of his death on the internet.

In Syria and Iraq, among the main victims of Baghdadi’s organization, residents expressed relief at the demise of the man who presided over the self-styled caliphate.

In the Iraqi city of Mosul, still in ruins two years after it was liberated from Islamic State, there was no closure.

“His death is a fraction of the sins and misdeeds he inflicted on the victims who lost their lives in the Old City area and whose bodies until now are still under the rubble. All because of him and his organization,” said resident Mudhir Abdul Qadir.

“We hope that the culture of Al-Baghdadi’s and Daesh is killed forever.... Killing this culture is the real victory,” said Mehdi Sultan, a government employee in the Iraqi capital, Baghdad.

Like others, however, he was not optimistic. “One Al-Baghdadi goes out, another comes in. It’s the same old story.”

Perhaps nowhere is Baghdadi more reviled than among Iraq’s Yazidis, who are still unable to return home or locate hundreds of women and children kidnapped and enslaved by Islamic State five years ago. The Yazidis are followers of an ancient religion with ties to Zoroastrianism.

The militants rampaged through northern Iraq’s Sinjar region in August 2014, destroying villages and religious sites, kidnapping thousands of women and children, and trading them in modern-day slavery. The United Nations called the attacks genocide.

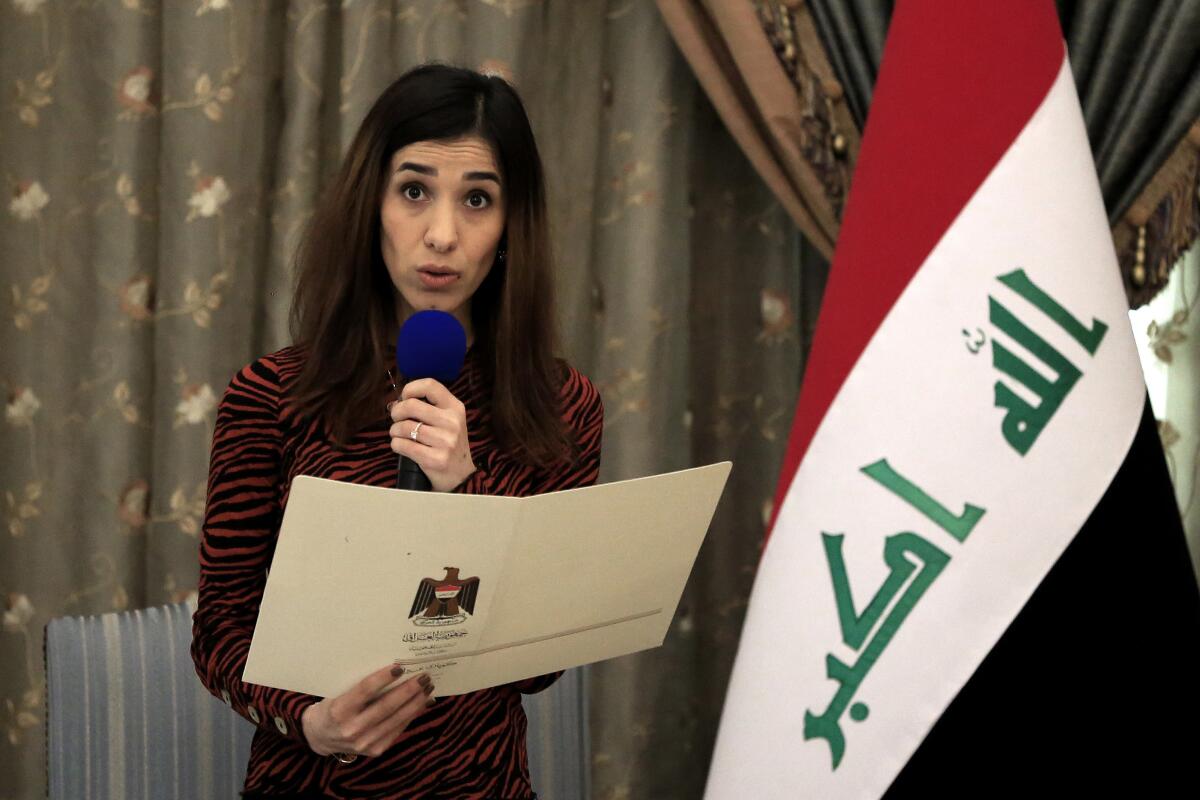

Nadia Murad, a Yazidi woman who was among those kidnapped and enslaved, welcomed the news of Baghdadi’s death.

“Al-Baghdadi died as he lived — a coward using children as a shield. Let today be the beginning of the global fight to bring ISIS to justice,” she tweeted.

Murad, who won a Nobel Peace Prize for her activism against genocide and sexual violence, called for all those Islamic State members captured alive to be brought to justice in an open court for the world to see.

“We must unite and hold ISIS terrorists accountable in the same way the world tried the Nazis in an open court at the Nuremberg trials,” she wrote.

Associated Press writers Samuel Petrequin in Brussels; Josef Federman in Jerusalem; Omar Akour in Al-Karak, Jordan; Salar Salim in Irbil, Iraq; and Ali Abdul-Hassan in Baghdad contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.