Latinx Files: The effects of Trump’s family separation

On Sunday, the Atlantic published a lengthy investigation — it clocks in at nearly 30,000 words — by Caitlin Dickerson that explains in great detail how the Trump administration implemented a ‘zero tolerance’ immigration policy that led to thousands of families being separated.

Dickerson’s investigation lays out how Trump’s family separation machine was built in secrecy. According to her report, the idea to prosecute migrant parents and take their children away first came to Tom Homan, former acting director of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement under Trump, in the summer of 2014, while he was working for the Obama administration (it’s worth mentioning that one critique I’ve seen of this report is that it sanitizes Obama’s own immigration record by pinning it all on Trump). Dickerson reports that Homan pitched the idea then, but was shut down.

Much of the focus of the investigation is on the palace intrigue between the hawks advocating for the policy and the career bureaucrats who opposed it. The former camp clearly won out, implementing a plan whose cruelty was made worse by the administration’s trademark incompetence. Dickerson writes:

“A flagrant failure to prepare meant that courts, detention centers, and children’s shelters became dangerously overwhelmed; that parents and children were lost to each other, sometimes many states apart; that four years later, some families are still separated — and that even many of those who have been reunited have suffered irreparable harm.”

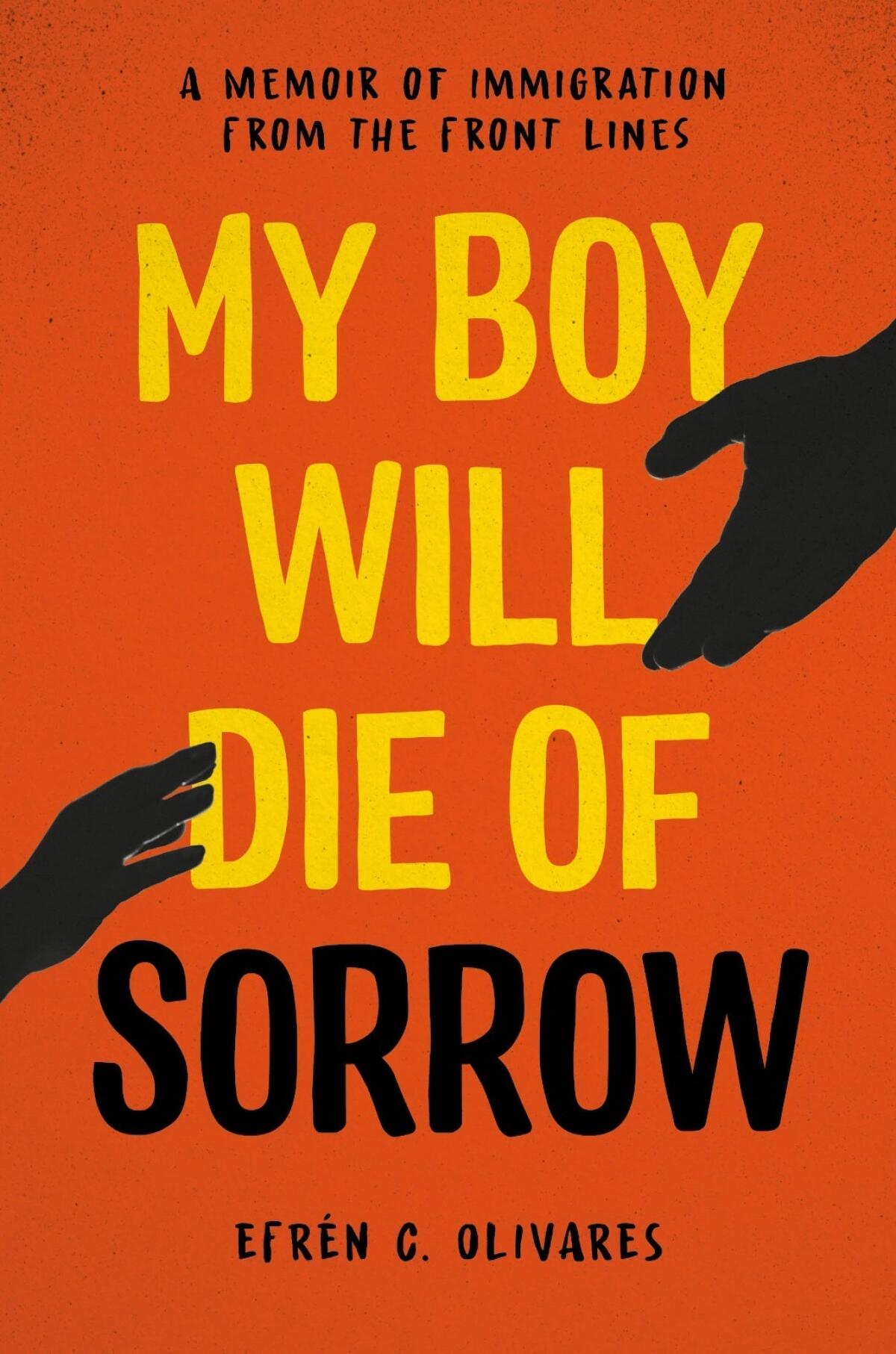

The Atlantic’s story comes on the heels of the July publication of Efrén C. Olivares’ memoir “My Boy Will Die of Sorrow.” Olivares (full disclosure: we went to high school together) is currently the deputy director for immigrant justice at the Southern Poverty Law Center, but in the summer of 2018 he worked for the Texas Civil Rights Project and was one of many lawyers across the country who worked to reunite some of the separated families in the wake of “zero tolerance.” The book tells the story about this policy as experienced on the ground while also adding important historical context that indicates that this policy was not created in a vacuum.

I spoke to Olivares about his book and Trump’s family separation policy. The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Your book is a memoir about your experience suing the federal government over family separation, but your own family’s migration story is interwoven in. What led to that decision?

The idea for that came out of a presentation I gave at my alma mater to a group of first-generation college students. My work regarding family separation began in the summer of 2017, and in the spring of 2019 I was invited to speak at the University of Pennsylvania to talk about my experience as a first-generation immigrant in the U.S. and first-generation college student, as well as the work we were doing representing immigrant families. That was the first time I started seeing some parallels. I thought to myself, “Yeah, I guess back when I was a child, I never thought of my experiences as a type of family separation, but yeah, my dad would leave and be gone for three weeks and then come back for a weekend.” I started seeing some parallels in the immigrant experience that were applicable to myself and to my clients and to other immigrants that I know.

Putting it in historical context, what happened in 2018 was just the tip of the iceberg. Family separations have happened before and they continue to happen today. It’s a part of a lot of families’ immigration stories. Only one relative can go. The other needs to wait. They think they’re going to be separated for a week, and it turns out to be five years. Things like that are more common than we realize, and they don’t happen in a vacuum. No laws were changed in order for zero tolerance to happen. It was the same laws that were on the books, it was the same agencies that were there and are still here, and it was critically the same Border Patrol agents who were taking children from their parents in 2018 that are today detaining immigrants. It is naïve to think that [2018] was a crisis and we solved it, because it continues to happen.

Interesting that you bring that up because my dad worked in refineries along the Texas Gulf Coast Monday through Friday when I was growing up and then come back for the weekend, and that setup definitely affects you. I’ll admit that it was somewhat traumatic, but you and I are the lucky ones, right? We have citizenship. I can’t imagine the trauma experienced by the people who came to the border without really knowing what was going to happen, with a lot of unknowns. But even that is still worth it when compared to the alternative, to stay in a place that is no longer feasible because of issues of safety or economics.

Right, and people often make the case that, “Well, they chose to come, it’s the parents’ fault for bringing their children.” Leaving your home, your community, your country, your language, your culture, sometimes only with what’s in your backpack and starting over in a country you don’t know anything about, it’s not something people do by choice. They’re pushed into it as a last resort. It is the only option they have left. That’s when people pick up and leave. No matter how many border walls are built or what the policy at the border is, if people are facing bad circumstances in their home countries, they’re going to leave. They’re going to do what it takes to find safety and opportunity. Human beings have been doing that for millennia. We’ve always moved across the globe looking for safety and opportunity. It’s the most human thing to do.

One of the things I hope the book pushes readers to do is to make them ask themselves why we think of those who came in the past as heroes and pioneers, but see those who are coming today as either looking for a handout or bringing disease.

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

There were two parts in your book where you talk about the media that I thought were really interesting. The first seemed like a critique, an implication that it is complicit in terms of sanitizing what’s really happening. You specifically mention the New York Times, citing an article from 1915 that portrayed two unaccompanied Colombian children as being largely content while in detention, as well as a 2012 report that claims that unaccompanied children sometimes remember their detention “as some of the best times in their battered lives.” What role do you think the media plays when it comes to this issue?

Stories like these are supposed to make us feel better. The readers of the New York Times, or whatever newspaper it may be because this is not about the New York Times in particular, come away thinking, “Oh, it’s not so bad. They’re really happy. They remember it fondly.”

I do think it’s part of this removed coverage of the border and immigration. Certain outlets and certain reporters who are always pretending to be mere observers, detached observers who are not part of the policy and are not part of the decision. That’s one thing I very much did not want to do [with the book], because I am an immigrant myself and I wanted to show that perspective.

The second time you bring up the media relates to ProPublica and Neta RGV releasing leaked audio from inside a detention center where you hear separated children wailing and asking for their parents. In your book, you mention how the clip affected you as a father. Why was this news development so important?

It took me more than 24 hours after it came out to sit down and draw the courage to listen to it. For weeks I had been wondering whether someone was going to leak a photo or video of what was going inside these facilities, maybe some agent would have a conscience and share with the rest of the world what they are seeing. But it never crossed my mind that it would be audio, which turned out to be the perfect medium because it shared the cries of the children without showing the color of their skin. And that really connected with listeners from across the political spectrum, even people who had been in favor of this policy. When they heard that audio, something clicked. It made people think that it could be their child.

I thought the audio made it too clear and too visceral that a line had been crossed. It’s what caused widespread outrage against the policy. And shortly after it came out, President Trump signed an executive order purporting to end the separations. In actuality, the order didn’t fully end the practice, but it certainly decreased the volume or the number of separations that were happening every day.

The other thing about it is with cell phones being everywhere, it was likely a cell phone that recorded that audio. One of the differences of the 2018 crisis is that information travels very quickly these days and spreads around in a way that wasn’t the case during the internment of Japanese Americans, immigrants and citizens alike, during World War II. We only have written accounts of what happened. The same applies to Ellis Island or the Chinese Exclusion Act or even the bracero program.

Can you explain what happened after Trump signed the executive order supposedly ending “zero tolerance” and family separation?

About 4,000 or so children had already been separated from their parents by the time Trump issued his executive order, which said nothing about reuniting them. There was also no way to enforce it.

I met and spoke directly with parents who were separated from their children after the executive order was signed. The practice of family separation continued to happen at a lower rate than before, but it kept happening because there was no way to enforce the executive order. And there were no consequences for anyone. It took another lawsuit and court enforcement to make the Trump administration stop for good.

Going back to the video, another thing that stood out to me was that the Border Patrol agents in the audio were Spanish speakers, which isn’t particularly surprising given how many agents have Spanish surnames. They’re people that could have gone to high school with us. What are your thoughts on that?

I think it’s a confluence of factors that drive people who are from the border, who are immigrants themselves or the children of immigrants, to join an agency whose mission it is to stop immigrants from coming to this country. There are economic pressures, the lack of better job opportunities. It’s a federal job with good benefits that doesn’t require a college degree, and if you’re someone who for whatever reason decided or couldn’t go to college, it’s one of the better-paying jobs available along the border. People take jobs for different reasons, but there are structural barriers in place that keep certain people from aspiring to have good-paying jobs that don’t depend on the carceral state, jobs that don’t involve ripping children away. I don’t think it’s fair or accurate to pin this on individual decisions in the sense of, “Well, this person chose to go work for Border Patrol!” The system is designed to push Black and brown, low-income folks to take these jobs.

I do want to challenge the prominent myth of “my ancestors did it the right way,” because 40, 50 years ago was a very different time period than today. The laws and processes were different. For decades, the border between Mexico and the U.S. was pretty open. There was no checkpoint. People came and went with the jobs. So to say that your ancestors did it the right way and that those coming today are doing it wrong belies the arbitrariness of immigration law and policy changes.

Do you think it’s going to get better? I ask because there’s definitely a push to give more funding to law enforcement. For example, here in Los Angeles, mayoral candidate Karen Bass, ostensibly a liberal Democrat, has come out in favor of hiring more police. Similarly, President Joe Biden’s recent proposed budget included billions more for law enforcement. Given that U.S. Customs and Border Protection is the largest federal law enforcement agency, it stands to reason that some of this money would go to them. How do you see the next five years playing out when it comes to immigration?

A good friend of mine likes to say that not everything is lost. There’s still a lot more to lose. The annual budget of the Border Patrol and ICE has grown consistently year after year over the last 20 years regardless of what the number of crossings at the border, the number of people coming, say. It’s gotten out of control, but it’s always politically expedient and convenient for elected officials to say, “I support law enforcement and we’re going to secure the border and pour more money into it!” Pouring more money into it is a popular talking point when election time rolls around, but it is devoid of any real policy analysis that asks if it’s what we should be doing. Is this really where our tax dollars should be going?

I have moved away from this idea that the arc of history bends toward justice. It does not bend in any direction. It’s incumbent upon us, those who care about human rights and about justice, to push and bend the damn thing in the right direction. It’s on us to keep pushing our elected officials not only during election times but also after they are elected, to push them into doing the right thing because otherwise somebody else is going to be speaking into their ear.

Think of the recent Supreme Court decision [that overturned Roe v. Wade] that has really taken away the rights of millions of people in this country. Is that the arc of history bending towards justice? I don’t think so. That’s what we have to contend with. We’ve got to do our best, use the tools that we have — whether it is legal tools or organizing tools, grassroots tools, media and advocacy tools — to keep pushing and demanding that those rights be respected, not only for people who can get pregnant, but for every single individual who has been historically oppressed and marginalized in this country. It’s going to be incumbent upon us to keep making that call daily and loudly.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Things we read this week that we think you should read

— My colleague Jean Guerrero wrote about the cancellation of “The Gordita Chronicles” and the endemic erasure of Latinx stories in the media we consume and financially prop up.

—And speaking of Latinx erasure, Times columnist Carolina Miranda employs my favorite form of criticism — ridicule — to lambast the decision to cast James Franco as Fidel Castro in an upcoming film (which, lol, the only way this movie isn’t going to be remotely terrible is if Franco decides to play Tommy Wiseau playing the Cuban dictator). Why stop at James Franco, Miranda says.

“If you’re going to whitewash, GO ALL THE WAY. Make it so awkward and unbearable that people will remember it with the same embarrassed wonder they generally reserve for that hot tub sex scene in ‘Showgirls.’”

To help the producers make the most whitewashed Cuban film since “Scarface,” Miranda enlisted author Rosa Lowinger to cast the rest of the movie. My personal favorite is the rather inspired choice for Fulgencio Batista.

– L.A. Taco is reporting that yet another food vendor has been harrassed, this time in Long Beach.

— What I’m listening to: I really enjoyed this episode of “El Pochcast,” which goes into the origins of the chupacabra, a modern-day cryptid that gained popularity thanks to segments on Univision’s “Primer Impacto.” Host Rodrigo Nuñez points out that these segments are nothing short of sensationalized disinformation. The episode made me think about how prevalent Spanish-language disinformation is on social media, and whether the popular infotainment program bears some responsibility, if any, for priming audiences to be susceptible to it. I linked to Spotify above; for Apple podcasts, click here.

From the “Sign up NOW!” Department: The L.A. Times newsletter team is launching Group Therapy, a weekly newsletter focusing on mental health. Every Tuesday, staff writer Laura Newberry will be answering questions sent in by readers.

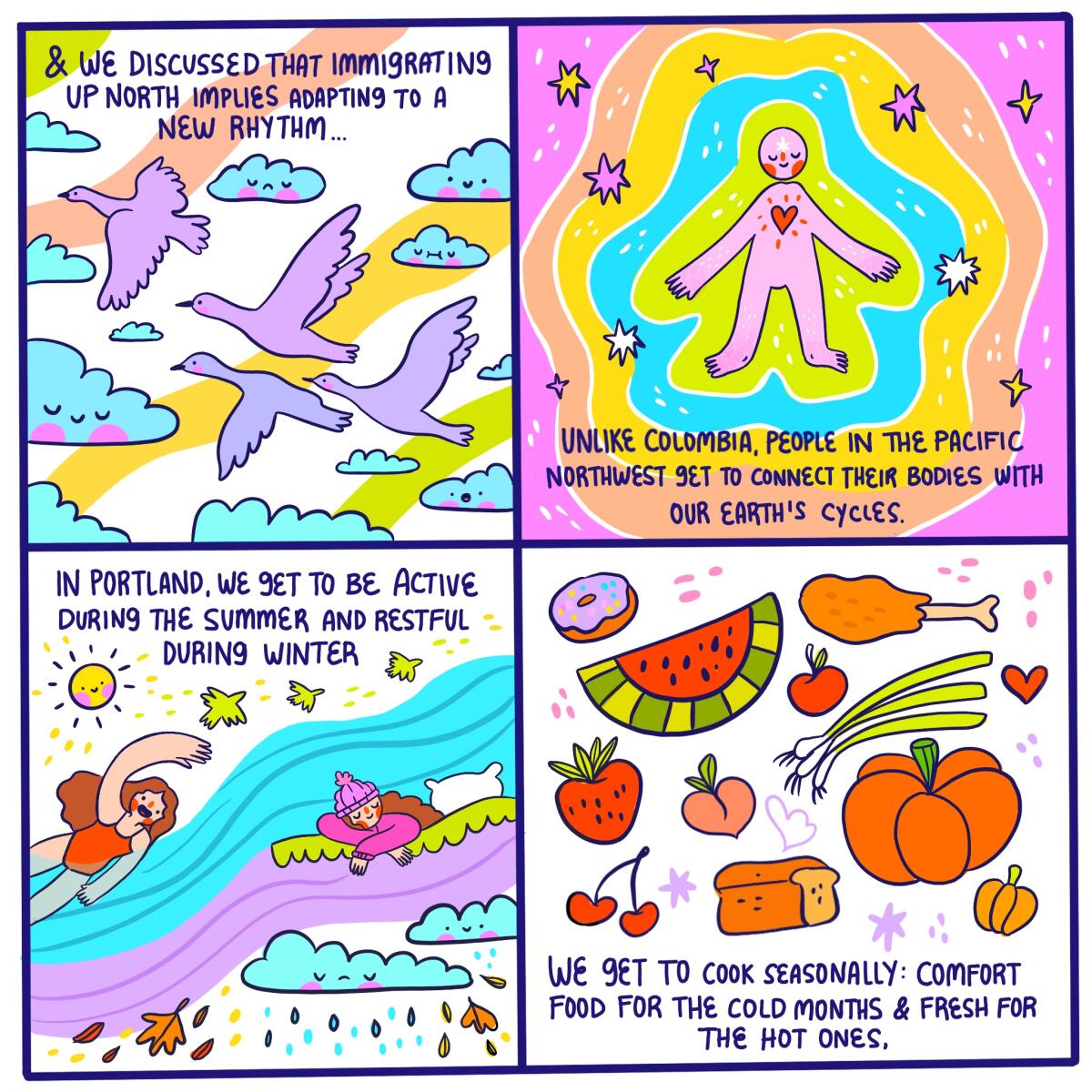

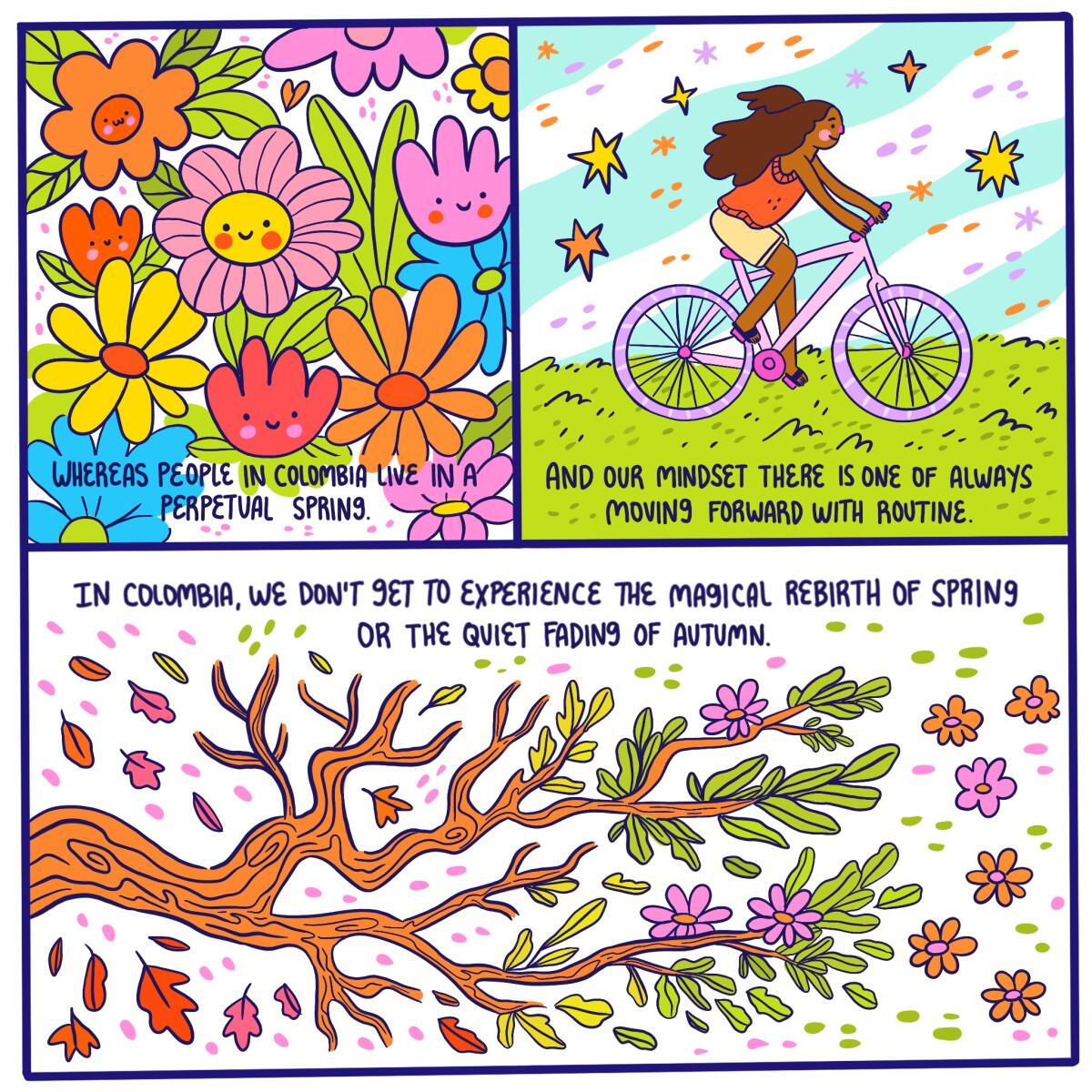

The Magic of the Seasons

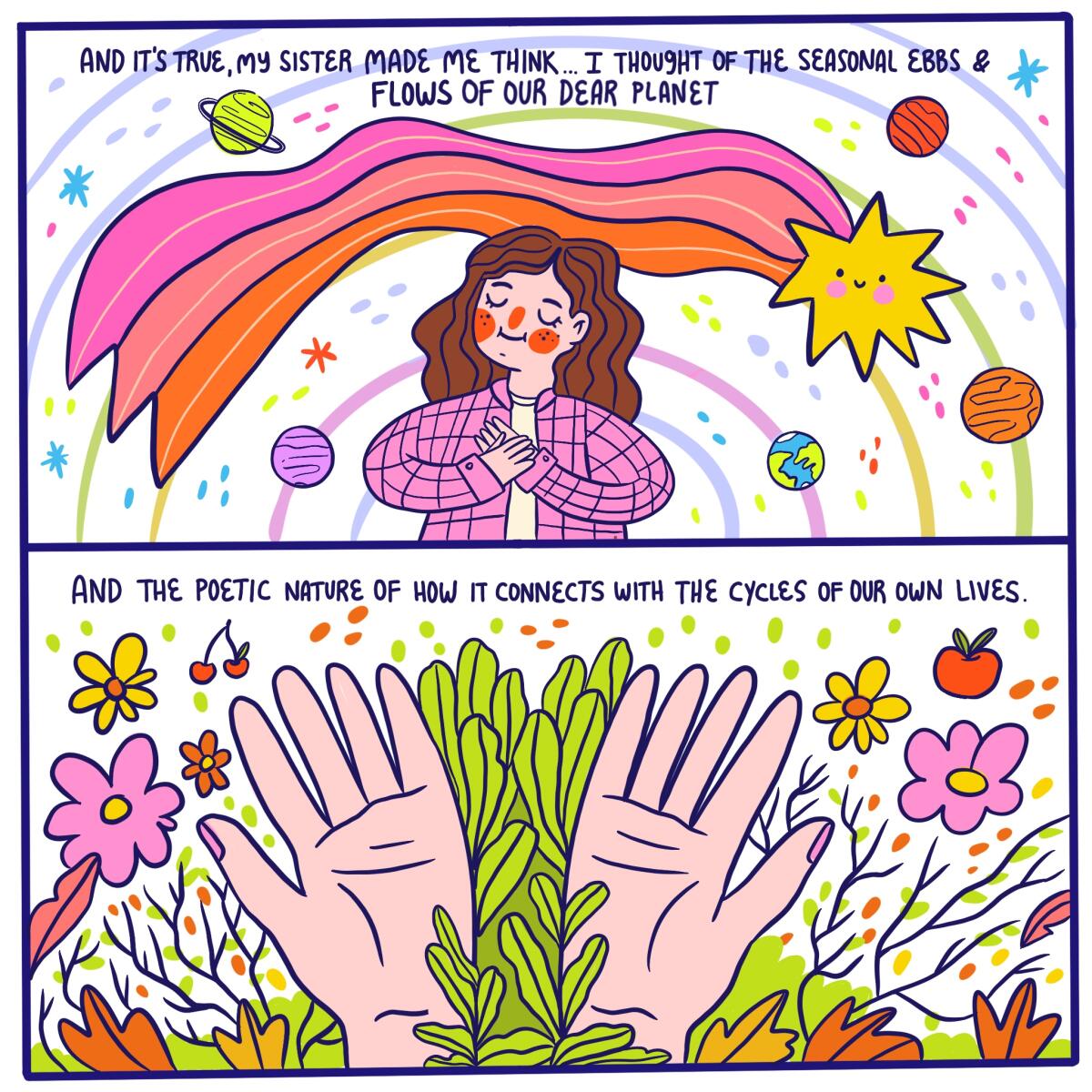

Natalia Cardona Puerta is a Colombian illustrator and designer based in Portland, Ore. “My work draws inspiration from the warmth of my home country, my childhood in the ‘90s and my whimsical relationship with nature. I love spending time in my art studio with my cat, Scoots, designing illustrated products, books, murals and more!

“When I first arrived in the U.S., getting used to living with seasons has been both a challenge and a source of inspiration. ‘The Magic of the Seasons’ is a comic based on a conversation I had with my sister Adela, in which we drew parallels between our lives in Colombia and Portland. It’s a visual poem about nostalgia and curiosity that invites you to analyze different points of view, and how the rhythms of our planet connect us all.”

Are you a Latinx artist? We want your help telling our stories. Send us your pitches for illustrations, comics, GIFs and more! Email our art director at [email protected].

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.