Latinx Files: Exploring Selena’s legacy, from concerts to classrooms to Netflix

Hello and welcome to the Latinx Files. I’m Fidel Martinez, and it’s Thursday, Dec. 3. (Is this your first Latinx Files newsletter? Have questions about the name? We have an explainer for that.)

By this time tomorrow, Netflix will have released the first half of “Selena: The Series.” The first nine episodes of the long-awaited drama focus on the early struggles that the Tejano queen and her family band Los Dinos faced on their road to stardom.

I’m not a betting man — years of working in sports have taught me that the unexpected always happens — but if I were, I’d wager that the Netflix show will be a massive success. I don’t need to tell you that anything slapped with Selena’s name will be a moneymaker. I’m looking at you, MAC Cosmetics and Funko.

So far, “Selena: The Series” has had mixed reviews. My colleague Lorraine Ali thought it missed the mark, that it focused too much on Abraham and A.B. Quintanilla — the “dadager” and songwriting brother, respectively — and less on Selena.

I’ll spare you my thoughts because quite frankly I’m more interested in what you have to say about it. Seriously, send me an email at [email protected] and tell me what you think.

The one thing I will say is that as a native of South Texas, where much of this story takes place, I was pleasantly taken aback to see names, faces and places that I grew up with. I really enjoyed seeing Pete Astudillo, a Tejano icon in his own right if only for that mullet, be recognized as the creative genius that he is. I also appreciated that the showrunners acknowledged the role that the legendary variety show host Johnny Canales played in helping launch Selena’s career — so much so that I even wrote a primer on “The Johnny Canales Show” and its legacy.

Retelling Selena’s story is no easy task. How could it be? Selena, along with Pacoima’s own Ritchie Valens, pelotero Roberto Clemente and comedian Freddie Prinze, are on the Latinx Mt. Rushmore of icons who were gone way too soon. (I’ve often wondered if that common thread, one of unfulfilled potential, is part of the broader Latinx ethos.)

The magnitude of this herculean task was not lost on actor Christian Serratos, who plays Selena.

I “knew I was never going to make everybody happy,” Serratos told my colleague Yvonne Villareal. “I knew that because she had that star quality. We all feel a sense of ownership when it comes to Selena — that’s my homie, that’s my family, that’s my sister.”

It doesn’t make it any easier when fans already have “Selena,” the 1997 Gregory Nava film that’s so ubiquitous it’s been memefied — “Anything for Selenas.”

Still, Jaime Dávila, one of the executive producers on “Selena: The Series,” hopes that the likely success of the Netflix show will open the door for Latinx creatives to tell stories other than Selena’s.

“More than anything, we’re trying to show Hollywood that there’s this huge market of Latinx/Latino people; that our stories are American stories; that our stories are global stories,” he told Yvonne for her profile of Dávila and his company Campanario.

“Being able to point to a story like ‘Selena: The Series,’ which is all of those things, is really great. I would love for more doors to open up.”

I would love that, too. But given Hollywood’s track record, I’ll believe it when I see it.

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The time we went to go see Selena

One of the privileges of growing up in the Rio Grande Valley during the early ’90s was living in a time and place where seeing Selena in concert was a thing that people could do. My family did, in 1993 at the Feria de Reynosa across the border.

Miraculously, footage of that show exists online. Check out her questionable dreadlocks. Notice the tracking!

The specifics of what became our first concert experience are vague — I was 8 years old at the time, my brother Jeb was 6, and my sister Gloria was 4. Our recollection of that night can’t be trusted, so I spoke with my dad, my mom, y mi abuelita Paula — my maternal grandmother — for a more accurate account of what happened.

What everyone seems to remember is the size of the crowd.

“Fuimos a verla porque ella era de la gente,” my mom explained of Selena’s “of the people” image, pointing out that Reynosa’s annual fair had two stages: el palenque, which required paid admission, and el teatro del pueblo.

“El teatro del pueblo era para todos,” she added. “Era un ambiente más familiar.”

That’s her euphemistic way of saying that the concert was free. And because there was no charge and Selena was at the height of her fame, families like mine packed the venue long before the star — our star — was scheduled to perform. We arrived early, but not early enough.

Despite the packed crowd, everybody was calm. That lasted only until the band walked onstage.

“Se desordenó,” my old man told me. “El público se volvió loco, todos querían verla, todos se amontonaron.”

The orderly audience turned into a hysterical crowd wanting to be as close to Selena as possible. That included my grandmother and my sister.

“I remember wanting to see her up close, so Grandma took me by the hand saying, ‘vente, vente, vente!’ and then we started crawling under the benches until we got to the pit,” Gloria said.

“Nos fuimos muy emocionadas, y pues orale! Nos metimos por debajo de las bancas y nos cruzamos por debajo como soldados,” Paulita said, confirming my sister’s account of their mission.

“Tu abuelo se puso bien enojado después porque fuimos hacer el ridículo.”

My grandfather was furious, she said. I couldn’t confirm this with Lazaro because he was napping when I called, but it checks out.

In the end, my sister Gloria claims it was worth it just to have a glimpse of Selena. My grandmother insists it was too crowded for them to see.

“Gloria will say that not only did she get to see her, but that Selena invited her up to dance with her and even took her backstage,” Jeb joked of my sister’s propensity to view the past with a much rosier outlook.

Jeb doesn’t remember much, but my dad told me the two of us stayed back with him and took turns going up on his shoulders.

I asked my dad what he thought of a bunch of Mexicans in Mexico going this crazy for an American. A Mexican American, but an American no less.

“Pues su carisma era tan grande así,” he said after pausing to reflect on my question. “A la gente no les importo que era de allá.”

That’s when it hit me: The narrative that Selena was killed before she had a chance to cross over isn’t a real one. She did. Into Mexico, into a place where anything with roots north of the border is met with initial suspicion. That, to me, is a testament of just how big of a star she was and continues to be.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Meet Sonya M. Alemán, the professor teaching the class on Selena

Sonya M. Alemán, a professor of Mexican American studies at the University of Texas at San Antonio (go Roadrunners!), began teaching a class on Selena, identity and her legacy. I spoke to Alemán about her course and why young people love the Tejano icon so much. Here are some highlights form our hourlong conversation. Her comments have been lightly edited for clarity.

It’s been over 25 years since Selena’s murder, and yet she still resonates so much with people, especially younger people of a different generation who claim her as their own. Why is that?

I designed my course around that very question because I just knew that there was an untapped opportunity to explore Mexican American identity and experiences rooted in what Selena means to this community and what she represents.

What was really interesting for me was recognizing that there is this newer generation who continue to adore her and feel this devotion. Where does that come from if they don’t have those firsthand types of memories that you and I have? Without that, what is it that continues to draw what we’re calling the second generation of Selena fans, those born after her death? I really think it’s going to be a multifaceted answer, but one component is that it’s become quite clear that for many of these younger fans, Selena is embedded in how they practice their Mexican American culture. So for them, she’s part of quinceañeras, she’s part of family celebrations, she’s part of hanging out with cousins and learning how to dance. She’s part of all of those memories. To them, she means family. She means home. Selena is a marker of their cultural identity as much as a piñata or the custom of the mordida and the birthday cake. She’s just what we do, they said.

What is it about Selena and her public persona that has made people, especially younger people, turn her into a marker of identity?

I think it is rooted in the history of the community that she comes from. It’s this history of marginalization that marks the Mexican American and Latinx experience. She is a symbol of the untapped potential of this community as a result of that marginalization. So she symbolizes all that we’re capable of doing and achieving. I think part of her staying power, one of the main factors of it, is that she had to work really hard for the success that she achieved, and she never forgot what it was like to come from nothing. Her family was working class. They were poor for most of her career as a singer and weren’t living in the lap of luxury from day one. When she did get famous, she always maintained that humility. I think that’s something that’s very attractive to communities who have been denigrated for holding on to those values. The fact that she clung to them amidst her success is very appealing.

And we can’t ignore the tragic way that she died. It’s like a microcosm of that kind of marginalization. But what it also did was freeze her at that moment. Had she been able to fulfill her life and her potential and crossed over into U.S. mainstream pop culture, it’s very likely that she would have lost some of those elements that made her so specifically Tejana, so specifically Mexican American, because of the nature of that industry. In order to continue along the path of success, Selena would have had to make some concessions to fit into that world. We never had to see her do that, and that’s something that we hold dear, the fact that she was always just this one way for us.

In thinking about Selena and bicultural identity, one of the things that stands out to me about her is that someone who didn’t even speak Spanish that well wasn’t seen as an American by Mexican crowds. They embraced her fully. So in a weird way, she sort of achieved something that many of us never have and never will, quite frankly.

Yeah, I think one of the many reasons to continue to admire her, to continue to recognize her as an icon, is that she was so comfortable with herself, with all the parts of who she was, that she was able to get other people to accept her completely.

Some of the people my students have interviewed have indicated that their love for Selena is partly rooted in the fact that she made it OK for them to also love themselves because they were not native Spanish speakers, because they were still struggling to learn the language, because they felt sort of removed from this particular heritage. That continues to be a key element of her appeal, and that’s significant.

Meet our Latinx colleagues: Yvonne Villarreal

This week, I’d like to highlight the work of Yvonne Villarreal, who plays a key role in our television coverage. Not only was she responsible for writing the bulk of our Selena coverage, but she will also co-host the new Los Angeles Times podcast “The Envelope,” which will focus on the truly bizarre and unprecedented upcoming awards season. (Sign up for the Envelope newsletter for the latest news and podcast episodes.)

A Southern California native, Yvonne loves TV. When you were watching cartoons as a child, she was watching “I Love Lucy” reruns. You can find her on Twitter at @villarrealy. You can also join her, Selena and her parents (or the actors who play them), “Selena: The Series” creator Moises Zamora and chefs Susan Feniger and Mary Sue Milliken for a Tex-Mex meal and conversation taking place Saturday night.

Things we’ve read or seen that we think you should read or see

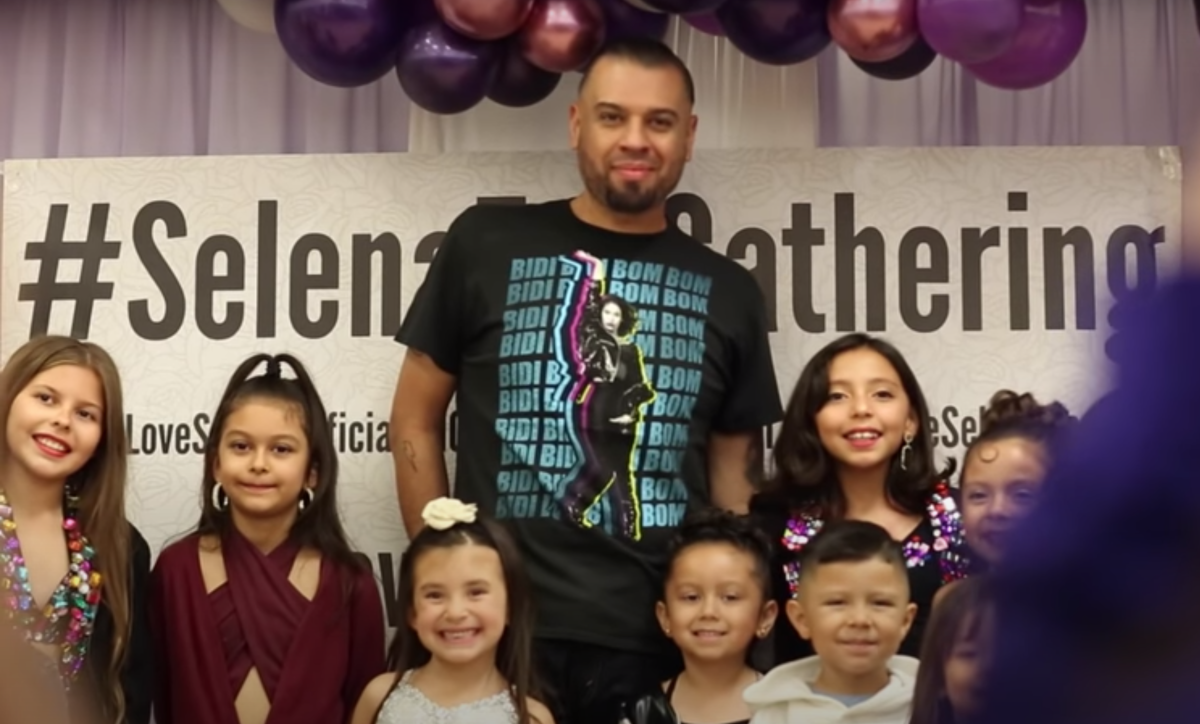

— Last year the homie Steve Saldivar (no relation to Yolanda, he said), a fantastic video journalist at The Times, headed down to the Plaza de la Raza in Los Angeles’ Lincoln Park to speak with attendees of the annual Selena Fan Gathering about their undying love for Selena. The event took place this year virtually because of COVID-19.

— For many, it’s sacrilege to express anything that’s not a full-throated endorsement of anything Selena-related, but for Vice’s Alex Zaragoza, the new Netflix series is more of the same and a testament to the kinds of stories Hollywood is willing to tell about Latinxs. Her thoughtful piece also takes aim at the complicity of Latinx-centric media companies in this.

— One of the more familiar threads of the Selena narrative is the acrimony between Chris Perez, Selena’s widower, and Abraham Quintanilla, her dad. That rancor appears to be very much alive today. Billboard’s Jesse Katz takes a deep dive into the legal battle over Selena’s estate and who gets to tell her story.

— Over at WBUR, Maria Garcia is launching a podcast aptly called “Anything for Selena,” about belonging in a space where neither part of her identity — ni de aquí, ni de allá — makes it easy to feel that way.

— Esta va para toda la gente que le gusta la musica Tejana: The good folks over at San Antonio’s KSAT have this really cool 20-minute video primer on the rise and decline of Tejano, a genre that was the soundtrack to my life before the internet.

The best thing on the Latinternet: Selena’s final appearance on “The Johnny Canales Show”

Please enjoy Selena’s 1994 appearance on “The Johnny Canales Show.” It was her final one and took place a year before she was murdered by Yolanda Saldivar.

I don’t know about you, but it really has me in my feels.

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.