From the Archives: 1967 antiwar protest turns violent

On June 23, 1967, President Lyndon Johnson arrived at Century City to deliver a speech at a Democratic Party fundraiser. Ten thousand anti-Vietnam War protesters also arrived.

In a June 23, 1997, Los Angeles Times article, staff writer Kenneth Reich reported:

The war at home over Vietnam had yet to explode in mid-1967. Five hundred American soldiers were dying every month, yet 40% of Americans still supported sending more men.

So 30 years ago tonight, when a coalition of 80 antiwar groups staged a march to the Century Plaza Hotel where President Lyndon B. Johnson was being honored, Los Angeles Police Department field commander John A. McAllister expected 1,000 or 2,000 protesters.

“When the mass of humanity came up Avenue of the Stars and over the hill, I was astounded,” he recalled. “Where did all those people come from? I asked myself.

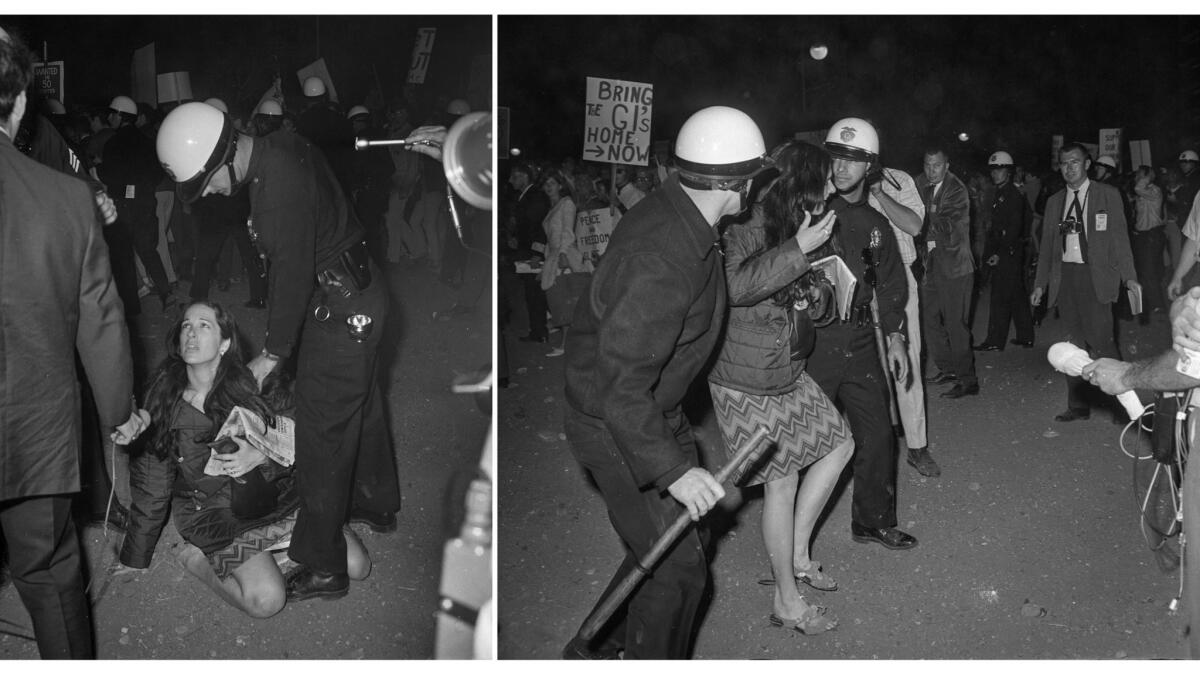

Ten thousand marchers, by most estimates, were assembling across the street from the Century City hotel. Hundreds of nightstick-wielding police — using a parade permit and court order that restricted the marchers from stopping to demonstrate — forcibly dispersed them.

The bloody, panicked clash that ensued left an indelible mark on politics, protests and police relations. It marked a turning point for Los Angeles, a city not known for drawing demonstrators to marches in sizable numbers.

The significance of the evening lay not simply in the 51 people who were arrested and the scores injured when 500 of the 1,300 police on the scene pushed the demonstrators into, and then beyond, a vacant lot that is now the site of the ABC Entertainment Center.

Far more powerfully, the Century Plaza confrontation foreshadowed the explosive growth of the national antiwar movement and its inevitable confrontations with police. It shaped the movement’s rising militancy, particularly among the sizable number of middle-class protesters who expected to do nothing more than chant against Johnson outside the $1,000-a-plate Democratic Party fundraising dinner and were outraged by the LAPD’s hard-line tactics.

Johnson rarely campaigned in public again, except for appearances at safe places like military bases. Within nine months, opposition to the war grew so strong that he shelved his reelection campaign. White liberals in Los Angeles, meanwhile, began to complain about excessive force by the LAPD, a subject traditionally raised only by black and Latino residents.

By the next summer, when Chicago police beat demonstrators in the street outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention, the country was at war with itself. In retrospect, the Century Plaza demonstration was one of the earliest battlegrounds. …

The original idea was to stage a march from Rancho Park, up Pico Boulevard and past the hotel on Avenue of the Stars, then turn onto Santa Monica Boulevard and go home. But as the marchers reached the hotel, a vanguard of radicals ignored the terms of the police permit and sat down in the street.

The march halted. Police said they issued a dispersal order several times on a powerful loudspeaker, but many demonstrators said that in all the noise and chants they failed to hear it.

Then hundreds of officers moved in, their nightsticks held in front of them, pushing the demonstrators away. Some of the people fought back. Some photographs show police swinging their nightsticks at marchers who were not resisting. A particularly bitter clash took place under the Olympic Boulevard bridge. …

Here’s a link to Reich’s full story: The Bloody March that Shook L.A.

See more from the Los Angeles Times archives here

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.