Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

San Simeon, Calif. — One recent morning, a dozen Barbary sheep started to shamble across the main road to Hearst Castle, then stopped in the middle.

And why not? They hadn’t seen a loaded tour bus on that road since March.

As the state wages a seesaw battle against the coronavirus, the castle’s keepers confront the challenge of reopening a historic site that depends on bus transportation and has no air filtration system. Nobody is sure when California’s most famous mansion will reopen, including Dan Falat, superintendent of the California State Parks district that includes the castle.

Get inspired to get away.

Explore California, the West and beyond with the weekly Escapes newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The castle stands about 230 miles northwest of Los Angeles, halfway to San Francisco, a location that helped, until now, make it a prime tourist attraction for decades.

At its Roman Pool, where 1,800 tourists per day no longer pass by, the freshly scrubbed tiles have never looked bluer. In most of the compound’s 165 artifact-filled rooms, there’s less dust than usual — because, as curator Toby Selyem explained, there aren’t visitors shedding dead skin as they shuffle past.

The castle’s museum director, Mary Levkoff, retired in July with no successor named so far.

Another awkward detail about the castle: “We happen to be in the middle of our 100th anniversary right now,” said Falat, sounding like a groom whose bride has run off with the caterer. “We were actually getting ready to kick it off in April.”

But like millions of other homeowners who have been filling their pandemic days with long-postponed household projects, the team on the Hearst Castle hilltop has a long list of chores.

Workers are trying to revive and clone an ailing oak tree, to replace rusted iron with stainless steel wherever possible, to power-wash tiles, to pluck ash from pool filters.

They’re also trying to calculate how many COVID-era tourists can safely fit on a 54-seat bus — perhaps 13? maybe 27? — and how many can stand in the grand Assembly Room where publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst once rubbed shoulders with Winston Churchill, Charlie Chaplin, Greta Garbo, Harpo Marx, Joan Crawford and Cecil Beaton.

Others are building new web content, placing plexiglass partitions at visitor center ticket windows and attacking projects that would be difficult or impossible with tourists underfoot.

The traditional museum challenge of balancing preservation and access is now a three-way endeavor: preservation versus access versus public health. (So far, none of Hearst Castle’s more than 100 employees has been laid off, Falat said, and fewer than five have tested positive for the coronavirus.)

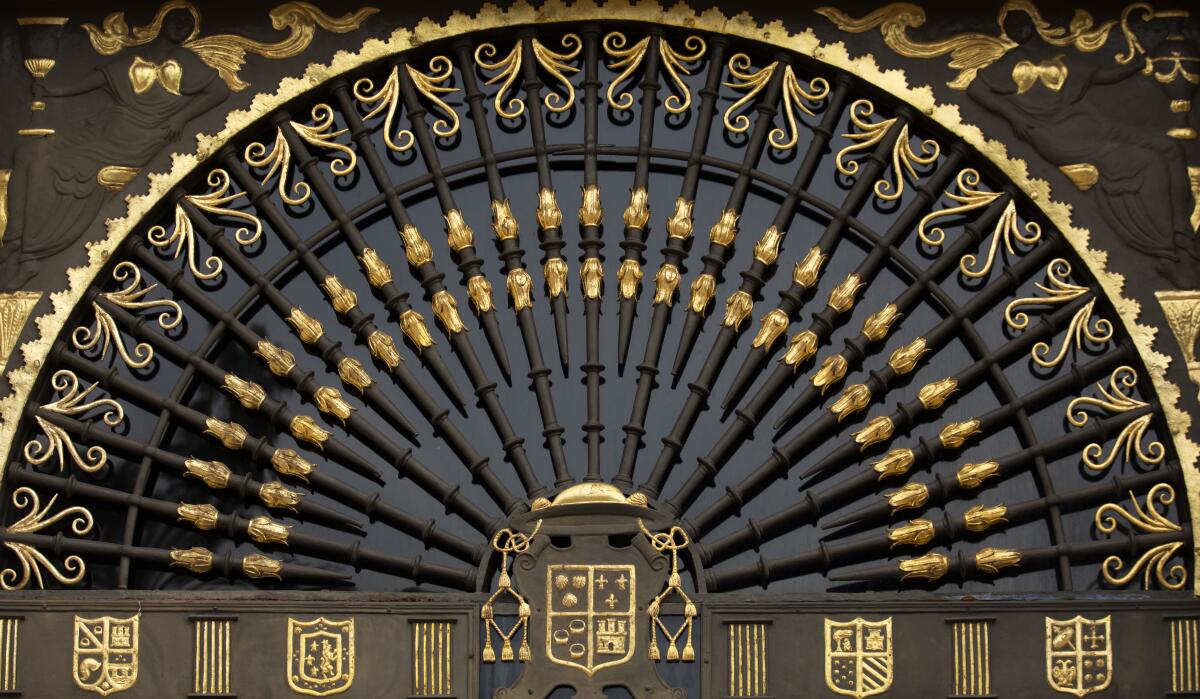

The castle is really a 127-acre compound of buildings dominated by Casa Grande, the principal residence, whose exterior resembles a cathedral that’s been smuggled out of southern Europe. Clustered around it are three guest houses; two pools; extensive gardens and tennis courts, all surrounded by the blond hills and stately oaks of the 80,000-acre Hearst Ranch, still owned by Hearst Corp.

The city has some of the most beautifully preserved architectural masterpieces in California. Hop in the car and let’s explore.

Here’s a sampling of what photographer Francine Orr and I found beyond the gates.

The visitor center is just off California 1. In normal times, 16 tour buses roll up and down the steep, 7-mile road between the visitor center and the castle complex, with two departures every 10 minutes in peak hours.

Now the buses sit idle at the bottom of the hill while the sheep, which prefer the high country, cross the road at will.

The animals, a North African species known as an aoudad, are descended from early occupants of Hearst’s private zoo. The same goes for the zebra, elk and several other species that roam the ranch lands.

Since the pandemic, “you definitely see them a little bit more now in the road,” Falat said. “They have a little bit more carte blanche.”

At the Roman Pool — the spectacularly tiled indoor space that is the last stop on most tours — workers have partially drained the water, pressure-washed areas that hadn’t been cleaned since the 1980s, re-plastered here and there, repaired glass mosaic tiles and set about replacing rusty iron railing with stainless steel sleeves.

The room’s eroded cork ceiling tiles still need repairing and resealing, a tricky job because the tennis courts are just above. But the blue room, dusted with gold leafing and empty of visitors, shimmers like a mirage.

Outside at the larger Neptune Pool, where marble statues are gathered like a weekend retreat of Greek and Roman gods, it’s been two years since workers finished a four-year leak-sealing project. But the nearby Dolan wildfire in September sent so much ash into the air (and then into the pool water) that workers had to double or triple their scheduled cleanings of the filter system.

On a normal day, the castle’s 36 carillon bells ring at noon, transmitting a pop or classical melody from a player piano in Casa Grande.

Not now. Because no visitors are on hand to listen, restoration specialist Ernie Riley climbed into the towers that house the bells and retrieved assorted carillon parts.

“Installed in 1932. They came from Belgium,” said castle historian Amy Hart, looking over several bells and related bits.

They bore the scars from 88 years in wet coastal air, so Riley was sand-blasting some parts and coating others with rust-resistant paints. And what, he was asked, about the rusty metal crowns above the bells.

“We’ll change that over to bronze,” he said.

Judging by the sound the black bear cubs make as they eat, they appreciate the snack. “That’s a happy sound ... a sound of contentment,” Ben Kilham says.

Meanwhile in a bedroom of the Casa del Sol guest house, museum technician Nicole Caldwell played a flashlight beam on the face of a sculpted child on a wall next to the fireplace. This was a recent project of conservator Gary Hulbert.

“Before Gary started cleaning this, you couldn’t see the blush in the cheeks,” Caldwell said.

Maintaining that renewed blush will be another challenge. The buildings, constructed in the 1920s and 1930s and protected as historic resources, have no air-purification or air-conditioning systems.

To protect the roughly 25,000 pieces of art and artifacts inside, the staff must rely on humidifiers, dehumidifiers, fans, doors and windows, which they adjust more or less constantly to keep humidity near 50%, to keep temperatures between 68 and 70, and to keep ash out during wildfires.

“That’s it?” said Caldwell, hearing the 25,000 figure. “Seems like so much more when you’re dusting.”

William Randolph Hearst, who inherited a mining fortune and built a publishing empire, launched his planning for the estate in 1919, after his mother’s death in the influenza epidemic of 1918.

He spent more than 25 years acquiring items, drawing and redrawing plans with architect Julia Morgan. The result, many experts have said, is a vast but disparate collection of European art and artifacts from many eras and locales, displayed cheek by jowl.

“It was a fantasy project,” said James Allen, public relations director of the castle.

Atop a 17th century Italian dining table set for 22 in the Refectory, Hearst liked to keep bottles of Heinz ketchup and French’s mustard at the ready. So they remain.

Whether you consider this castle the realm of an unpretentious potentate or the kingdom of kitsch, it made for many entertaining weekends. Hearst usually shared host duties with his longtime mistress, actress Marion Davies, while his wife, Millicent, remained in New York.

When he left his castle in 1947 for the last time because of health troubles, Hearst still viewed it as incomplete. He died in 1951. Seven years later, Hearst Corp. donated the hilltop and the 2-acre visitor center site to the state. Since then, more than 40 million tourists have come and gone.

It is a new-money outsider’s rebellion against old-money East Coast habits, a public park that was once a private residence, a haven where the elite played tennis and watched movies while much of America suffered through the Great Depression.

Before the pandemic, the castle was open 362 days per year, with four main tours offered at $25 and up for adults. About 650,000 visitors passed through last year, which made the castle one of the top earners in the state park system.

Getting the castle open again “really boils down to the movement of people,” Falat said.

Americans are banned from many nations, but these countries are open, with conditions.

As soon as state and county officials are satisfied that the pandemic is under control and new procedures are safe enough, Falat said, he’ll swing open those gates and resume the centennial celebration.

Still, it’s possible some of the castle keepers will look back wistfully upon these days.

“It’s easier without people,” whispered Caldwell, tongue in cheek. “I can make sassy comments while I’m cleaning the marble nudes.”

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.