Grim Kilmainham Gaol, a treasure of Irish independence

DUBLIN — It is not often that a prison is a must-see tourist attraction.

Welcome to Dublin, where the Kilmainham Gaol is a national treasure. It has been called an Irish Bastille.

The aging prison, last used in 1924, is a monument forever linked to the Irish independence movement. It was also used during the Irish Civil War (1922-1923). It has housed prisoners from various rebellions and Irish uprisings against the ruling British as far back at the late 18th century.

The Irish Free State was created by treaty in 1921.

But 1916 will be forever tied to Kilmainham. Fourteen leaders of the six-day Easter Rising were shot for treason in the prison yard. Two others were executed elsewhere. That led to the prison becoming a symbol of Irish pride.

Kilmainham is where Patrick Pearse, James Connolly, Joseph Plunkett, Sean MacDermott, Thomas MacDonough, Eamonn Ceannt, Thomas Clarke and others were jailed and executed by the ruling British.

On Easter Monday 1916, the revolutionary leaders opposed to British rule proclaimed the Declaration of Independence from Dublin’s post office on O’Connell Street. An uprising ensued.

The 16 executions played a major role in adding to public support for independence.

Four prisoners were shot to death by the Free Irish State later during the Civil War in the prison yard. The last prisoner held at Kilmainham was Eaman de Valera, who later became Irish prime minister and president.

Today it is the biggest unoccupied prison in Europe. The building, about three miles from the center of Dublin, is gray, grim and foreboding. It was built of sandstone and that produced damp conditions.

It is a massive gray hulk of a building. Its front wood is marked by a spy hatch. Above the door are carved the Five Devils of Kilmainham, five hissing snakes chained by the neck to represent control.

Today it is known as the Kilmainham Gaol Historical Museum and offers guided 90-minute tours of the facility. It includes a museum/education center that covers the heroic and tragic struggles from the 1780s to the 1920s.

The tour includes a stop at the high-walled outdoor Stonebreakers’ Yard where the leaders of the 1916 uprising were shot by firing squads.

You also visit the chapel where Joseph Plunkett, a poet ill with tuberculosis, and Grace Gifford were married in 1916 on the eve of his execution.

They were married in the chapel on May 4, 1916, with 20 British soldiers as witnesses. They were allowed 10 minutes alone together. Two hours later, the new groom was shot to death for treason as a leader of the Easter Rising.

The prison is dominated by the horseshoe-shaped Central Hall with its central vaulted space in the East Wing. It was built in 1862 with 100 cells on four levels flanking iron walkways and stairs, designed to provide maximum light, but to assure constant surveillance. There were spy holes in every cell door. It was all part of central control. Solitary confinement cells are under the floor.

One of the attractions there is a painting from 1923, Madonna of the Lilies by Grace Plunkett, who was imprisoned later that year.

The tour begins in the gaol’s West Wing with its gloomy, bleak and dimly lit corridors with individual cells. The stone treads in the hallways are worn smooth by time. The locks are rusted in place. It is a haunting and powerful place.

Six of the 1916 prisoners were held in this corridor where you can find political graffiti dating back to that time.

The old prison had been falling apart but a grass-roots group, the Kilmainham Gaol Restoration Society, was formed in 1960. That effort took 20 years. The prison was later turned back to the Irish government.

The prison has been featured in numerous films and TV series including In the Name of the Father, Michael Collins, The Escapist, The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones and The Face of Fu Manchu.

The prison was built 1792-1795. It was called the New Gaol, although its official name was the County of Dublin Gaol.

It was a general prison occupied largely by debtors and petty thieves. There were also sheep thieves, rapists, prostitutes and murderers. It was overcrowded, getting 9,052 new prisoners in 1850, the peak year. The cells, about 28 meters square, held up to five prisoners with a single candle for heat and light.

Many Kilmainham prisoners were shipped to Australia. It became a hard-labor prison in 1877.

World class city

Dublin, a city divided by the River Liffey, is a compact, flat, easy-to-walk city of 1 million.

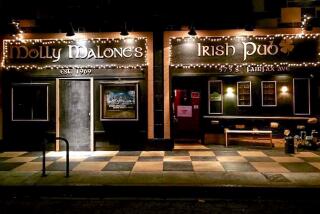

It has nearly 700 pubs, many with live music, and a colorful literary past: James Joyce, George Bernard Shaw, William Butler Yeats, Oscar Wilde, Samuel Beckett and Jonathan Swift.

You can visit the Dublin Writers’ Museum to see a first edition of Dracula written by Dublin-born Bram Stoker, and a chair used by Handel for his first performance of The Messiah in 1742. For information, go to https://www.writersmuseum.com.

Temple Bar, a neighborhood on the south side of the River Liffey, is filled with pubs, restaurants and shops. It has become one of the city’s most popular destinations.

The No. 1 tourist attraction in Dublin is the Guinness Storehouse, a seven-story, 170,000-square-foot tribute to the dark Irish stout made since 1759. It gets about 1 million visitors a year.

There are six floors of sleek, informative exhibits, topped by the Gravity Bar with its glass-walled, 360-degree views across Dublin. Visitors each get a pint of Guinness to go with the up-high views of the low-slung city. The glass-walled atrium is shaped like a pint glass.

The exhibits focus on beer making and Arthur Guinness. There is even a stop in the tasting room so guides offer instruction on the proper way to taste your Guinness.

The St. James Gate Brewery brews 3 million pints per day. It is the largest in Europe and is the second largest in the world, behind a newer Guinness brewery in Nigeria.

Admission is 14 euros ($19.10 American). For more information, go to https://www.Guinness-storehouse.com.

Perhaps Dublin’s greatest treasure is found at Trinity College. That’s where you can view the Book of Kells, illuminated gospel manuscripts from the ninth century.

The pages were started around 800 A.D. by monks in Iona, an island off the Scottish coast. It is thought that the gospels were completed in a monastery in Kells in County Meath outside Dublin. They were sent to Dublin for safekeeping in 1635.

The text of the four gospels is in Latin and the calligraphy and illustrations are stunning. Two of the four volumes are usually displayed: one showing illustrations and one showing text. The pages are turned every four months. There are 340 folios on high-quality calf vellum.

You can easily zip through the exhibit in 30 minutes, but be warned that it gets long lines. It opens at 9:30 a.m. For more information, go to https://www.tcd.ie/library/bookofkells.

For Dublin tourist information, go to https://www.ireland.com or https://www.visitdublin.com.

(c)2014 Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, Ohio)

Visit the Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, Ohio) at https://www.ohio.com

Distributed by MCT Information Services

PHOTOS (from MCT Photo Service, 202-383-6099):

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.