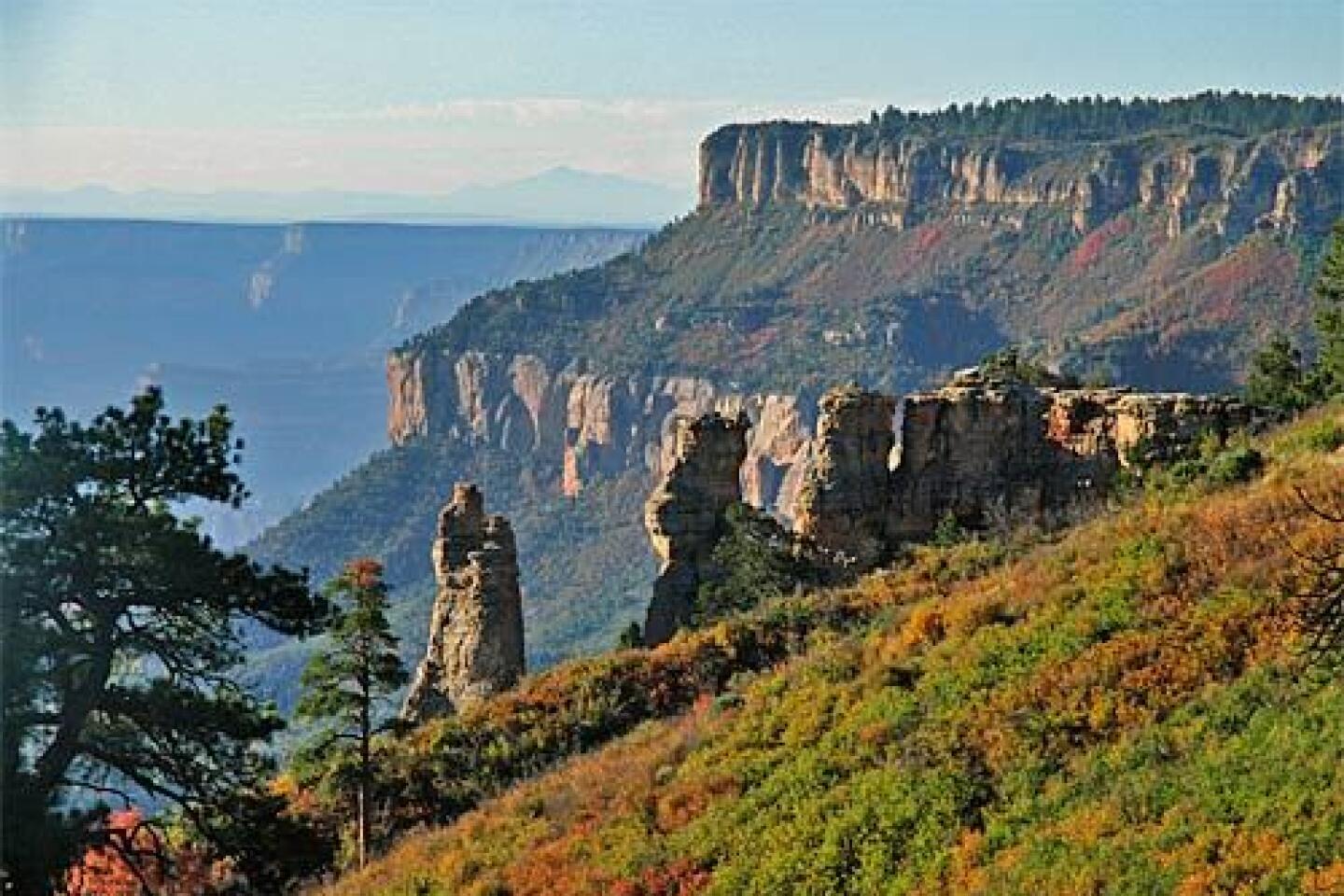

Drama along the Grand Canyon North Rim

Grand Canyon North Rim, Arizona

My brother, John, loves deserts, slot canyons, mesas, buttes and treacherous dirt roads. At home, he pores over U.S. Geological Survey maps, dog-ears pages in hiking books, studies dry treatises on the archaeology and geology of the Southwest.

Sometimes, he spreads out his camping gear on the patio -- camp stove, check; sleeping bag, check; headlamp, compass, TP, check, check, check. He has a special way of setting up a tent and you’d better get it right if you want to go with him.

And I do because he always takes me someplace remarkable -- Fish and Owl canyons in southeastern Utah; Haleakala Volcano on Maui; the old Mojave Road in eastern California; Picacho del Diablo in Baja.

When he said recently that he wanted to spend a few nights on the remote Powell Plateau, overlooking some of the finest vistas in the Grand Canyon, I immediately applied for a backcountry permit from the national park. I’d never been to the North Rim or heard of the Powell Plateau, but if John wanted to go there, that was all I needed to know.

Thinking we deserved a reward after the two-night camping trip, I tried to book a cabin at Grand Canyon Lodge on the North Rim, which was about to close for the season. I called for reservations and could hardly believe it when I learned it was full. Turns out, people make reservations months -- even years -- in advance for the fall, so I called every day for a week and finally got a place, thanks to a cancellation. But I wouldn’t count on luck getting you in. I’d start planning now.

Eons before my brother and I were born, seismic activity in what is now northern Arizona chopped a chunk about half the size of Catalina Island off the North Rim.

It came to rest between the rims of the chasm on the northern side of the Colorado River, which makes a big loop around it, 5,300 feet below. The top of the plateau is flat, and its flanks are steeply terraced, falling away from points along the edge that overlook a canyon land unknown to most tourists.

That’s partly because the Powell Plateau is reached by driving rough roads and hiking from the North Rim, which is far less visited than its southern counterpart: Of the 4.3 million people who went to the canyon last year, only 5% ventured to the North Rim.

Then, too, while the warmer, dryer, easily accessed South Rim stays open all year, the more remote North Rim closes when snow blocks the road -- around the beginning of November -- and doesn’t re-open until May.

A few tough canyoneers have circled its terraces and found plentiful evidence that the mysterious Anasazi people once lived here.

Theodore Roosevelt, cowboy fiction writer Zane Grey and Uncle Jimmy Owens, the old canyon codger immortalized in the 1953 children’s classic “Brighty of the Grand Canyon,” hunted cougars on the plateau. Colorado River explorer John Wesley Powell brought artist Thomas Moran here to paint the view from Dutton Point.

Around 1900, William Wallace Bass, an Easterner who had come to the arid Southwest for his health (upon first seeing the Grand Canyon, he said, “It nearly scared me to death.”), put his money on attracting tourists to the region around Powell Plateau.

He built a camp across from the plateau on the South Rim; cobbled together old Indian and prospector paths into the first cross-canyon route passable by horses, now the national park’s tough North and South Bass trails; and put a ferry boat in the river to take visitors across the Colorado to another camp underneath the plateau.

He knew in his gut that this was the heart of the canyon. But in 1901, the Grand Canyon Railway reached the head of Bright Angel Trail on the South Rim, 30 miles east, putting Bass out of business.

HUMMER HAPPY

I flew, and John drove his old Toyota 4Runner loaded with gear, from L.A. to Las Vegas, a good staging point for trips into the canyon lands of Utah and Arizona. He has logged 245,000 chassis-battering miles in that vehicle, and I don’t trust it. So I rented an SUV at the airport, where John met me.

When the woman at the rental check-in counter said we could upgrade to a Hummer for $10 a day more, John’s ears got as big as a mule deer’s. Driving a Hummer on an abominable dirt road is the stuff of his fantasies, and the price was unbeatable.

So we began our Powell Plateau adventure like a pair of rap stars, cruising down the Vegas Strip in an H3.

Early the next morning, we were on our way to St. George, Utah, where we would turn east toward the North Rim, with the Vermilion Cliffs at one shoulder and the Arizona Strip (the part of the state north of the canyon) at the other.

John kept telling me to drive faster or we would never make it to the plateau by dark. The rest of the time, he played with the H3’s accessories -- heated seats, satellite radio and a GPS unit that didn’t include the town of Jacob Lake, Ariz., where North Rim visitors turn south to Grand Canyon National Park.

At the Kaibab National Forest ranger station in Fredonia, Ariz., we got directions to the Powell Plateau trail head. To get there, we took a turnoff on Arizona 67 about 20 miles short of the North Rim lodge. Then we picked our way over a network of unpaved forest roads that led west to secluded canyon overlooks on the ragged southern edge of the Kaibab Plateau.

At Swamp Point, we parked the Hummer and started hiking.

To see us together, you wouldn’t necessarily know that my brother and I are actually quite fond of each other. I talk too much, which annoys him. He treats me like a galley slave. But on our little adventures in the great outdoors, we usually rediscover that we appreciate some of the same things, including peak experiences provided by Mother Nature.

She was generous that October afternoon. The aspens on the road to the North Rim had turned a bright, blazing canary yellow. Suddenly, we realized why the lodge was full. Fall comes to the North Rim in a geologic nanosecond, quickly whipped away by high winds and early snowfall. But if you’re lucky enough to be here at exactly the right moment, as we were, you will see an autumn display that blows the red maples of New England out of the water.

Along the way, John and I also saw evidence of man’s efforts to control the fires that regularly gut big tracts of ponderosa pine in the area. The national park and adjacent national forest used to suppress them vigorously.

But about 20 years ago, forest managers realized that fire is a natural part of the ecosystem, clearing out flammable undergrowth and thinning the trees, leaving only the hardiest ponderosas to grow into goliaths.

The authorities still battle conflagrations that threaten development and irreplaceable sites, but some are allowed to burn, although they’re carefully monitored. They even set prescribed fires to keep the forest healthy.

The trouble is, you can’t predict fire. Some North Rim road shoulders were seared on June 25, 2006, when sudden high winds turned a closely watched, lightning-ignited fire into an inferno, setting the crown of the forest alight. About 40,000 acres of Kaibab ponderosas burned in a single night.

After a fire like that, a new crop of brush and trees claims squatters’ rights in the cleared spaces, including beautiful intruders like the aspen.

At first, we overshot the Swamp Ridge Road turnoff, ending up at Fire Point, where we met a couple in a camper who said it had rained the day before. That was important information. The Powell Plateau is a lightning trap. People die in canyon electrical storms, and even experts can’t agree about how best to take cover from possible strikes.

Back on the right track, we saw pond-size puddles in the road. But the sun was out, and the H3 plowed right through them, although we had to stop when we saw what we took for a bison slurping from a pothole. (Later, we learned that part of a bison herd imported to Arizona around 1900 and cross-bred with cattle -- cattalo, they call them -- had escaped onto the Kaibab, degrading trails and water sources. Some years ago, the national park tried unsuccessfully to eradicate them. Travelers on Kaibab forest roads sometimes still encounter the creatures.)

Swamp Point turned out to be an exposed, 7,565-foot shelf of rock that would make a good place to shoot a Jeep commercial. It looks over White Creek and the North Bass Trail on their way to the basement of the Grand Canyon. I couldn’t see the Colorado River from here, but John pointed to a saddle of land below the point, where you can see an old cabin, and the land mass on the far side. “That’s the Powell Plateau,” he said.

By then, it was already 5 p.m. We figured we could make it 800 feet down to the Muav Saddle, cross the canyon and climb 900 more feet on a clearly visible trail that switchbacks over the terraced northeastern flank of the plateau, about 2 1/2 miles, all told.

We did it in a little more than an hour, pitched our tents in the twilight and had freeze-dried chili mac for dinner.

We had been hiking in shirt sleeves, but John said I had better bundle up for the night. It was going to get cold. It could even snow.

At 7:30, I went to bed in three pairs of long johns, a hooded sweat shirt, jacket, gloves, socks and my sleeping bag. Even then, I felt as though I were sleeping on ice.

SHEAR BLISS

No matter how well-prepared you are, you take a calculated risk going into the wilderness. John is an experienced backpacker with a high risk threshold. Mine is so low that a falling pine cone can make me panic. Plus, I’d been reading “Deep Survival” by Laurence Gonzales, which uses neuroscience and true stories of disasters to explain who dies in the wilderness and why.

But the next morning, I felt safe and cozy. The birds were singing, and the sun was rising in a cloudless sky. Once we packed, John and I followed the teasing Dutton Point trail through golden meadows where asters and daisies lingered.

We frequently lost the trail, which was unmaintained and only occasionally marked with blazes and cairns. But after thrashing around a bit, we generally found it again.

Maybe we were too busy looking at the bizarrely shaped, blackened husks of ponderosas -- ghost trees, John called them --that lightning had selected for death. Lightning starts most North Rim fires, and the plateau’s remoteness has made it a testing ground for the let-it-burn strategy of forest management. So, the top is a rare example of an almost virgin ponderosa pine forest, much thinner than you would expect for a Western forest primeval.

Around noon, we made camp on the edge of the plateau, where my open-sided tent-tarp looked into the canyon. We lazed around in the sunshine, then walked a few miles to Dutton Point. When we reached the edge of the plateau, John went first onto the overhanging ledge.

“Come on,” he yelled back. “It’s like a dance floor out here.”

I crawled, hardly daring to look up. But when I did, I forgot I was on a 7,500-foot-high rock ledge. The view was magnificent, at least 180 degrees of prime Grand Canyon panorama wrapped around the southeastern corner of the Powell Plateau.

Far below, the Colorado pushed west to Lake Mead after its long meander through the big ditch.

We could see everything: the South Rim, clearly lower than the North; the 6,242-foot Masonic Temple, with its razorback ridge leading to Fan Island butte; King Arthur Castle and Galahad Point; even white water in what we deduced to be the Colorado’s Serpentine Rapids.

Only when the shadows lengthened did we leave the ledge. Back at camp, we ate turkey tetrazzini for dinner and went to bed, mostly in silence. There wasn’t much to say after a day that had been blissful from sunrise to sunset.

LOST . . . AND FOUND

It still amazes me how fast things changed.

I started hearing the wind in the middle of the night. It sounded like a vacuum cleaner. By the time I got up, the sky was roiling.

Without a word exchanged, John and I knew we had to get off the exposed plateau. He could scarcely believe how efficiently I packed, but as Gonzales says in “Deep Survival,” fear sometimes makes people focus. I admit I was afraid, knowing that weather, not mountain lions, is the chief predator on the Powell Plateau.

We left at 6:30 a.m. and made good time until we stopped seeing the trail markers. At first, we followed the plateau’s eastern rim, thinking it would inevitably lead us to the takeoff point for the cross-canyon route to Swamp Point, where we had left the Hummer.

But it didn’t, no matter how hard we bushwhacked through scrub oak, crossed dry drainages and looked for familiar ghost trees.

Finally, John made a difficult but smart decision. He made us backtrack to the eastern rim and then walk west across the plateau, figuring we would have to cross the trail on the way.

We spent more than an hour doing that while the sky grew increasingly ugly. My brother was tense with worry, which more than anything else made me decide that I had lived a good life but that I was ready to let go.

“I just don’t see how we could have missed the trail,” he said for about the fifth time.

My eyes were glued to the ground. At just that moment the light must have changed, because I suddenly realized I was looking at a slightly worn place in the grass that could be a trail.

“I think it’s right here,” I said. “I think we’re standing on it.”

We got off the plateau just in time, the first thunder booming as we climbed up from the Muav Saddle. When we reached Swamp Point, it started to pour. My clothes were sweaty-cold, so I was happy for the H3’s heated seats and the way the Hummer plowed right over Swamp Ridge Road.

At the national park checkpoint on Arizona 67, the attendant gave us a big smile when we said we had come from Powell Plateau. The front-desk clerk at the lodge put us in a cabin with a propane fireplace. While we waited for the cabin, to be cleaned, we had lunch in the dining room, feeling righteous.

During our two days at the lodge, John and I ate well, napped hard, attended ranger lectures and cheated at National Park Monopoly. Meanwhile, the lodge tucked up for winter, urged on by 70-mph winds.

A good trip usually has its panic and bliss. You go for the one and learn from the other. You get back in touch with matters elemental and remember who in the wide world you can always count on.

Powell Plateau was one for the scrapbook. But I know there will be others.

Email us your comments and feedback

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.