Celebrate St. Patrick’s Day in the most Irish place in the U.S.--and we’re not talking about Boston

If you’re stateside and feel like a cracking St. Patrick’s Day, you’ll want to be in America’s most Irish city. And that, surprisingly, is Butte, Mont. (per capita, anyway).

This once-booming mining town with a population of about 35,000 is a hilly grid of streets straddling the Continental Divide. Almost a quarter of Butte’s inhabitants are of Irish descent, compared with Boston’s one in five who can claim that heritage, according to the 2010 U.S. census.

I discovered this Irish side of the American West during a midlife hankering for change when I upped sticks from London and moved to Missoula, Mont.

More photos of Butte, Montana >>

I was prepared to fall in love with Montana’s sweeping landscapes and crystalline mountain light, but I was surprised that relocating there also meant getting in touch with my inner Celt.

The Hibernian history of the state dates to the 19th century, when the Irish were escaping decades of famine. In 1862, with the discovery of gold, thousands of Irish immigrants headed to what is now present-day Montana.

Then, as if to give the state a Celtic seal of approval, Montana got its first acting governor in the form of fiery Irish nationalist Thomas Francis Meagher (1823-1867).

You can see his fingerprints all over the region in the bars, restaurants and counties bearing his name.

After reading about this Byron-esque figure in Timothy Egan’s “The Immortal Irishman,” I was impelled to explore Montana’s hidden Irish side along with my own. And my journey started in Butte.

In the 1890s, prospectors in Butte struck gold and silver, giving the town its nickname, “The Richest Hill on Earth.” But it was the plentiful veins of copper that really got the place booming.

This precious metal made the likes of Marcus Daly — another escapee from the Irish famines — one of the wealthiest men in the world.

When Butte’s mines were running at their peak between 1880 and 1920, more Gaelic was spoken below its streets than anywhere outside the Emerald Isle.

You can see the Irish influence all over town, from Cavanaugh’s County Celtic shop, which bursts with First Communion dresses, tweeds and Waterford crystal, to the city’s annual An Rí Rá festival. (“Rí rá” means “chaos” or “hullabaloo”’ in Gaelic.)

This festival (Aug. 11-13) fills the sidewalks, bars and theaters with people from around the world who come for the Irish music, dancing and, of course, to sink a drink or two.

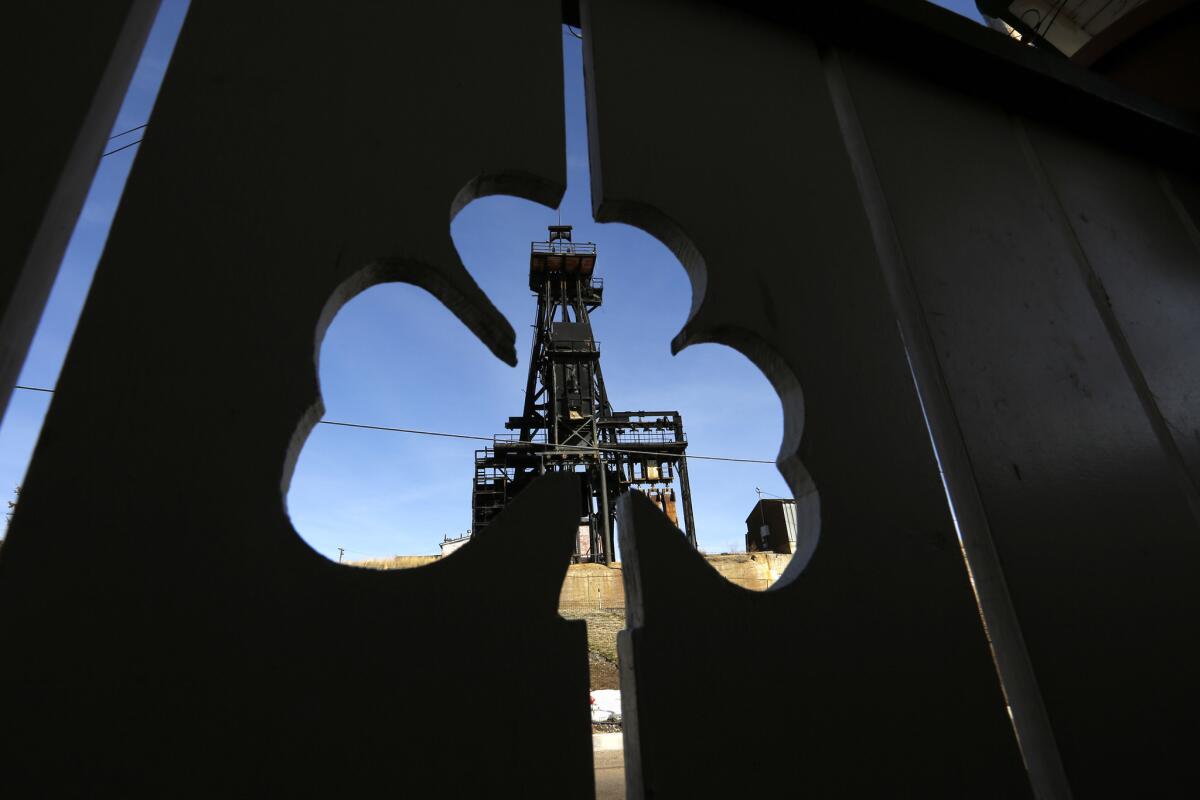

An Rí Rá may hold the honor of being the only festival in the U.S. (and probably anywhere for that matter) whose main stage is an old mine yard with its original head frame — one of those tall steel structures atop a mine shaft — now draped in fairy lights.

A visit to St. Patrick’s Cemetery in Butte also illustrates, although in a melancholy way, the town’s deep Irish roots. I found a headstone inscribed with my mother’s maiden name, which gave me the shivers. Montana was beginning to feel strangely familiar.

Butte’s 14 now-idle head frames and its almost 6,000 turn-of-the-last-century buildings make it among the largest — and perhaps least known — National Historic Landmark District in the U.S.

‘Irish roots, Montana soul’

To get a sense of Butte’s wealthy heyday, have a wander through Daly’s 24,000-square-foot summer home three hours west in Hamilton, Mont. The mansion, built in 1889, has 50 rooms, seven fireplaces and lots of Italian marble.

Lavish grounds provide the backdrop for the annual Bitterroot Celtic Games & Gathering (Aug. 19 and 20), where you can try Irish dancing, whiskey tasting, dog herding and, of course, Ireland’s national sport, the ancient game of hurling — a sort of cross between field hockey and soccer.

But it was Meagher (pronounced MAHR) who planted the first green shoots of Irish-ness in Montana.

His life is the stuff of a Hollywood action film: privileged childhood in Waterford, Ireland; nationalist leader whom Queen Victoria sentenced to “hanging and quartering” in 1848; death sentence commuted; exile in Australia’s Tasmania; escape to New York (aided by pirates, no less) in 1852.

Once in the Big Apple, he married wealthy socialite Elizabeth (Libby) Townsend, whose parents disowned her for choosing a Catholic, adventure-seeking husband.

Meagher, restless in the city, enlisted in the Union Army and led Irish soldiers during the Civil War. His intense combat experiences included the Battle of Antietam in Maryland, the bloodiest single-day fight on American soil.

After the war, Thomas and Libby settled in the territorial capital of Virginia City to assume his role as acting governor. In 1894, the town had more than 10,000 inhabitants, mostly gold miners. Today’s population of 190 gives Virginia City the feel of a living museum.

Walking tours take you past the Meaghers’ modest 500-square-foot log house, which Thomas and Libby comically called the “gubernatorial mansion.” Today you can catch a vaudeville show at the Virginia City Opera House, ride a stagecoach, pan for gold and, in the Bale of Hay Saloon, take a ghost tour between sips of microbrew.

Perhaps because the couple’s life in Virginia City was harsh, Meagher wanted to show his wife the beauty of the territory — a beauty that has crept under my skin.

In the summer of 1866, he and Libby headed west to a town whose name had just been changed from Hellgate Trading Post to Missoula. A tiny settlement back then, Missoula is now a thriving city of 71,000, full of brewpubs, galleries, cafés, farmers markets, outdoor outfitters and, not to be overlooked, Guinness on tap at the Thomas Meagher Bar.

From Missoula, Thomas and Libby went north to the Jesuit Mission of St. Ignatius,where Mass is still celebrated every Sunday.

Brother Joseph Carignano (1853-1919), a self-taught artist and the mission’s cook and handyman, painted 58 scenes from the Old and New Testaments that still adorn the walls and ceiling of this pretty red brick church.

Two works by Montana artists Sam and Olive Wiprud painted in 1960 depict Christ as an Indian chief and Mary with a baby on a cradle board, reminding visitors that they are on the Flathead Indian Reservation.

Overlooking the mission are the jagged, snow-capped Mission Mountains. It was during a hike in this range that Meagher apparently named a waterfall after his wife, although no one I know has been able to find it.

Once resettled in Virginia City, Meagher was called away to Fort Benton, a ragged, dusty town on the Missouri River.

This outpost was one of the largest inland ports in the U.S., servicing paddle boats and steamboats that plied the river carrying workers and goods.

Fort Benton’s handsome three-story Grand Union Hotel, built in 1882, is Montana’s oldest continuously running hotel and has been beautifully restored.

The old-world Union Grille Restaurant serves up-to-date meals with ingredients sourced from local farms, ranches and artisanal producers.

Unlike modern travelers who can enjoy the tranquillity of Fort Benton and a cocktail on the Grand Union’s terrace, Meagher had a less-than-relaxing experience.

He had been sent there by Gen. William T. Sherman to receive a shipment of firearms and ammunition for use against potential Indian uprisings.

Meagher, having suffered at the hands of the British for much of his life, equated the plight of the Native Americans with that of his beleaguered countrymen, and made this journey with a heavy heart.

On the night of July 1, 1867, the luck of this Irishman finally ran out. After accepting an invitation to dine with the captain of the riverboat, G.A. Thompson, Meagher went overboard into the Missouri River.

A witness described hearing his “despairing cries for the help that could not be offered.” Meagher’s body was never found, and his death is still shrouded in mystery.

In 1905, a statue of Meagher on horseback, raising his sword in defiance, was erected in Helena, Montana’s new state capital. On July 1, this will be the setting for the first Meagherfest, where live music and drama will be performed to mark the 150th anniversary of his untimely death.

In 2009, a bust of Meagher was placed on the banks of the Missouri River in Fort Benton. He looks toward the town, away from his watery grave.

Meagher was not one to turn away from mystery or hardship. Knowing him as I do now from Egan’s biography, I’m guessing that he would prefer to be gazing at the Mighty Mo, watching it flow high and fast with melting ice in spring, meandering lazily in summer’s heat, only to freeze and crack in winter. Who would want to turn away from the longest river in North America, as restless, changeable and elemental as the Immortal Irishman himself?

If you go

THE BEST WAY TO BUTTE, MONT.

From LAX, Delta offers connecting service (change of planes) to Butte. Restricted round-trip airfares from $312, including taxes and fees.

WHERE TO GO

Cavanaugh’s County Celtic, 131 W. Park St., Butte; (406) 723-1183

Saint Patrick’s Cemetery, South Montana Street, Butte. To find a specific grave, all records are kept at the offices of Holy Cross Cemetery, 4700 Harrison Ave.; (406) 494-3812

Daly Mansion, 251 Eastside Highway, Hamilton; (406) 363-6004

St. Ignatius Mission, 300 Bear Track Ave., St. Ignatius; (406) 745-2768

WHERE TO EAT AND DRINK

Thomas Meagher Bar, 130 W. Pine St., Missoula; (406) 540-4402

Grand Union Hotel and Union Grille Restaurant, 1 Grand Union Square, Fort Benton; (406) 622-1882

TO LEARN MORE

Montana Gaelic Cultural Society

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.