A sunrise bike ride down Hawaii’s Haleakala volcano

<p>Intrepid Times staff writer Chris Reynolds goes on a 27-mile bike ride down Haleakala volcano in Maui.</p>

Reporting from Haleakala, Hawaii — At Haleakala, it’s all downhill

Every day, about an hour after first light hits the green hillsides of upcountry Maui, the spokes begin to sing.

If you stand along the road by Sunrise Market in the hamlet of Kula, you’ll first hear the buzz, then with a whoosh the bicycles come around the bend: tourists by the dozen, their heads encased in heavy-duty helmets, their bodies wrapped in rain suits, their speed about 20 mph. They’re going 27 miles, following about two dozen switchbacks, rolling past hardened lava and cane fields, fruit stands, lazy livestock and three small towns. And 99% of it is downhill.

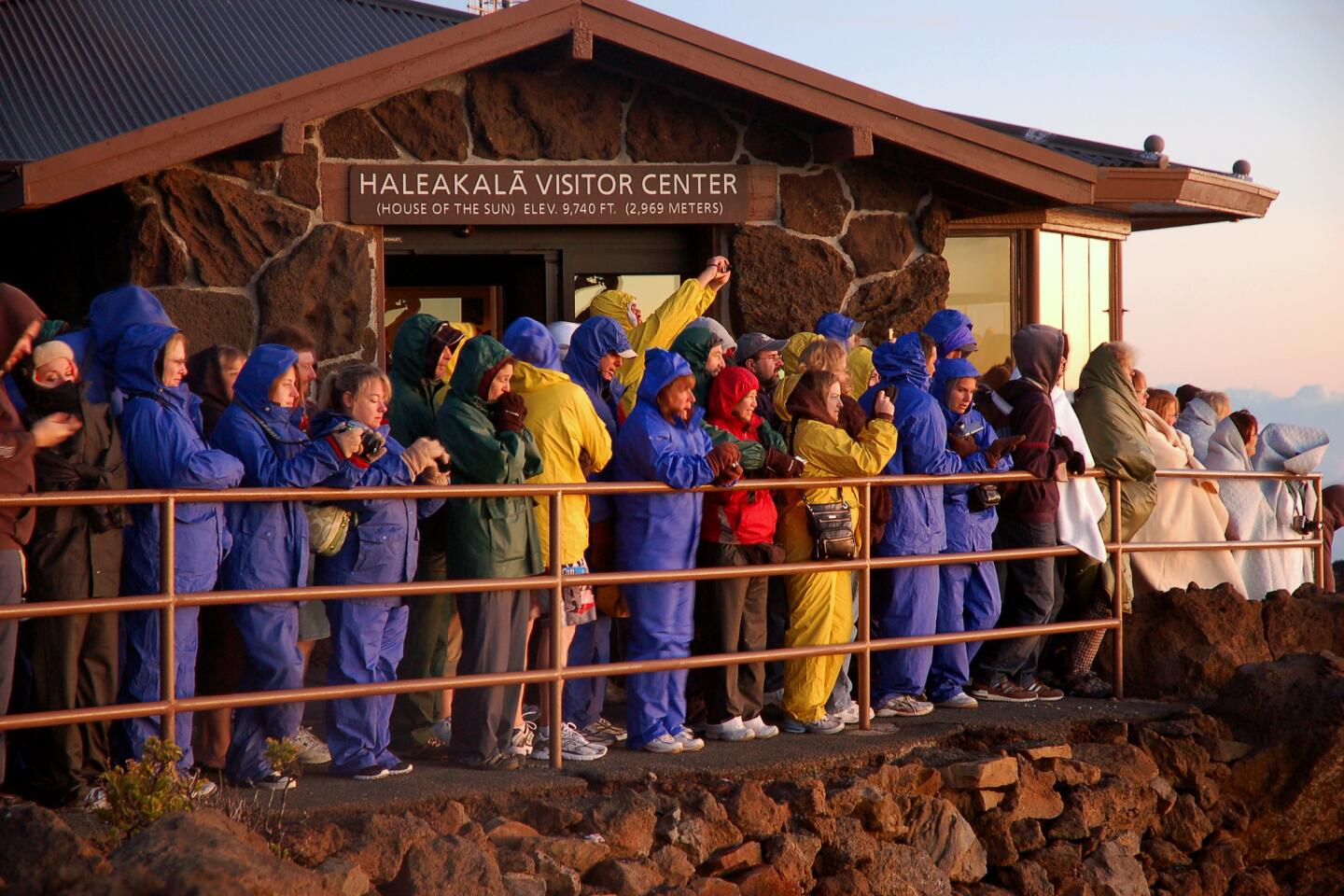

“It’s a little surreal,” says M. Sarah Creachbaum, who passes the riders every morning on her way to work as superintendent of Haleakala National Park. “They’re like space people, with the helmets and the colored outfits.”

On a busy day, 300 of these riders come around the bend, tempted by a simple, powerful, double-barreled idea: to see sunrise from the lip of Haleakala, a 10,000- foot Hawaiian volcano, then glide down the slope to the sea.

Seven companies on Maui hold permits to offer bike tours that begin with van or bus trips to sunrise viewings atop Haleakala. The guided rides go from the edge of the park to sea level, a 6,500-foot descent over about 27 miles of two-lane public roads.

Yet this ride can hurt you or even kill you.

In February, a 64-year-old rider from Mankato, Minn., died of head injuries after she crashed (she was wearing a helmet) into an embankment near the town of Makawao. She wasn’t the first. Since it first popped up in the 1980s, the volcano-ride trade has grown into a full-fledged industry, fallen into crisis amid a spate of injuries and deaths, then righted itself again. As many as 90,000 customers a year ride down Haleakala, typically paying $115 to $150 each for a sunrise tour and guided ride.

So how does it work, this balancing of risk and thrill on two wheels? One morning in late October, I signed on to find out.

At 2:45 a.m. — yes, you read that right — a bike-tour van picked me up at my hotel along the island’s western shore. After a stop to collect equipment and sign release forms with about a dozen fellow riders, we made the two-hour drive through the darkness to the top of Haleakala, passing the eerie glow of cane fires as we went. (Workers burn dried cane leaves in the fields as part of the harvest.)

At 5:15 a.m., we stepped out near the top, 9,740 feet above sea level, and into a parking lot crowded with hundreds of bundled-up tourists, a dawn of 40-degree gusts, numb digits, swirling clouds and volcanic moonscape, all of which erupted in golden light when the sun hurled its first beams at us from the horizon. Locals note that many winter sunrises are rain-soaked and cloud-bound, but this one was well worth the early wake.

For the seven bike-tour companies with permits to offer sunrise viewing and downhill rides, the day’s adventure was just getting started.

At 7:30 a.m., after transport to our starting point just outside the national park (about 6,500 feet above sea level), we saddled up and got a stern safety briefing from guides Everett Bennett (driving) and Joshua Sisson (riding). I chose Cruiser Phil’s, a small 12-year-old outfit, because it had done well in a 2008 National Park Service safety study (www.nps.gov/hale/parkmgmt/bikesafety.htm).

“I need you to ride defensively,” Sisson said. “I don’t mind if you take a quick glance at the view, but not on the hairpin turns. We’ve got a problem with guys getting halfway around these bends, whipping around and chatting with the dude behind them, and then missing the second half of the turn and going off the side of the road. I’ve seen it happen.”

Then, bundled up in jackets, gloves, rain suits and motocross helmets with chin-protectors, we rolled. Our one-speed Worksman bikes were heavy (why worry about weight when you’re going downhill?) and featured heavy-duty brakes.

One turn, two turns, three turns. Green valley, blue sea and, because the high ground is cattle country, the occasional cow pie. I expected to be intimidated, but I wasn’t — just invigorated.

“You’re looking out at the valley of Maui,” Bennett said when we paused to take pictures. “The north shore is over here.” To the west, he continued, “snorkel boats going out to Molokini. Lanai in the background. Windmills up on the ridge.”

What many cyclists don’t realize is that three years ago, this was a different ride.

In the old days — that is, from the 1980s until late 2007 — the classic Haleakala downhill route was 38 miles, not 27, and it began where those sunbeams struck us at the volcano’s lip. The first 11 miles were inside park boundaries, and they were fairly nasty, descending about 3,500 feet through a series of tight turns, with jagged rocks at the edge of the blacktop.

But tourists wanted to ride it anyway, including many who were overmatched. By 2007, about 90,000 riders a year were signing onto Haleakala downhill tour groups, and rangers were handling an average of five injury accidents every month.

On Sept. 26, 2007, a 65-year-old woman on a bike tour lost control on a curve near the summit, crossed the center line, collided with another company’s tour van, and died. By the park service’s tally, her death was the second within a year involving guided commercial downhill bicycle tours. Soon after, Marilyn H. Parris, then the park superintendent, temporarily banned commercial bike tours within the park.

In the months that followed, a compromise emerged: The volcano-bike tour buses would be allowed to carry their customers to the top of Haleakala for sunrise, but they would ferry their customers back down to 6,500 feet — just outside the park entrance — before beginning their rides. Below the park, the road isn’t as steep, the turns aren’t as sharp, and the roadside isn’t as rocky.

Three years later, while park officials continue to work on a long-term commercial-services plan, those rules still hold for all bike-tour companies. (Individuals can still ride from the top, but few do.) The result, locals say, is less bike-tour traffic and fewer accidents.

“It was crazy before,” said Ben Hokoana, a veteran guide with Maui Mountain Cruisers. “Much safer now.”

The Maui Police Department, which counted about two cycling injury accidents a month in the area in the mid-2000s, reported 10 in all of 2008, 19 in 2009, and five injury accidents — plus the one fatality — in the first nine months of 2010. Moreover, a police spokesman said, most of those accidents involved independent cyclists, not tours. Among tens of thousands of tour-group riders, police figures showed just nine injury accidents — and the one fatality — since January 2008.

By the time we reached Kula, 3,200 feet above sea level, I was running low on things to worry about. The grade was about 5%, and it felt gentle, perhaps because of the good visibility and the surrounding beauty, perhaps because the road was so smooth. In all of the city of Los Angeles, I doubt I could find 27 miles of blacktop in such great shape.

Traffic was thin. Though the route was on public roads and though some upcountry locals complain about cyclists snarling traffic, I saw mostly open road and probably more bikes than automobiles. When cars turned up behind us, we pulled over and let them pass.

Besides me (a once-a-month rider in the last days of his 40s), our group included a couple of young newlyweds, a 40ish man from England and a middle-aged couple from San Bernardino County — everyone between the ages of 15 and 65, all less than 270 pounds, and nobody pregnant, as Cruise Phil’s paperwork stipulates. Everyone looked comfortable on two wheels — and because I rode last in the single-file line, I got a good look.

“Very smooth ride,” said Rick Bell of Rancho Cucamonga, a few spots ahead of me. This might be what prompted me to ask Sisson the record for the fastest top-to-bottom ride.

“Fifty-eight minutes,” he said immediately. “And you’ve got to weigh more than 320 pounds to beat that record.” (The record-setting ride, Sisson explained later, was achieved several years ago at a “banzai race” staged by local riders on a night when the moon was full. I’m guessing no park rangers or police were invited.)

Many companies stop for breakfast in Kula. On the right side of the road sits the Sunrise Market and Protea Farm, which in the old days specialized in bikers’ lunches. These days, the bikes arrive sooner, and the main meal is breakfast, with chickens meandering underfoot as riders carry coffee and snacks between the cash register and a set of shaded picnic tables.

Just a few hundred yards farther along on the left, other groups stop at the Kula Lodge, a proper indoor restaurant with a fireplace, panoramic views, a gift shop, an art gallery, a fancy patio in back and several comfortable guest rooms. (If you have dinner and spend the night here, you can sleep until 5 and still make a 6:15 sunrise up top.)

We blew right past these places. The Cruiser Phil philosophy is to get down the hill before eating a full breakfast. By 9 a.m., we’d dropped down to about 1,600 feet above sea level, and the artsy outskirts of Makawao, where our guides waved us over and loaded our bikes into the trailer.

This wasn’t the end. Rather than annoy his neighbors by further clogging the main drag, Cruiser Phil has taken to busing his customers through the town, whose commercial strip of several blocks is full of galleries, boutiques, restaurants and cars pulling in and out. (Locals call Makawao a cowboy town, because it’s neighbored by a cattle ranch and it hosts a Fourth of July rodeo.)

As we saddled up again below Makawao for the last seven miles or so, Sisson told us to keep our mouths shut. Bugs, he said, are attracted to the neighboring cane and pineapple fields, and it’s never fun to swallow one at 20 mph. Sure enough, zipping past the open fields and the stone walls of an old church, I felt little winged creatures bouncing off my cheeks.

And then, in what seemed like no time at all, it was 9:45 a.m., and we were pulling into the parking lot of the Holy Rosary Church in Paia, about a mile from the beach. We were done. Subtracting standing-around time, we had averaged 24 mph.

“Normally, I do a hard cycle to work, commuting through London traffic,” said fellow rider Tim Clark. “Not pedaling, you just feel like a kid again, grinning side to side for 28 miles.”

As the crew loaded the bikes into the trailer and sorted helmets, we were free to check out the church shrine to Father Damien (who tended the lepers on Molokai in the late 19th century). Then we went on to choose breakfast places in the T-shaped tourist-and-surfer town of Paia. I went with crêpes on the patio of Café Des Amis.

But what I really wanted was 20 more miles of empty upcountry roads and an encore from those singing spokes.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.