Fellini’s Rome

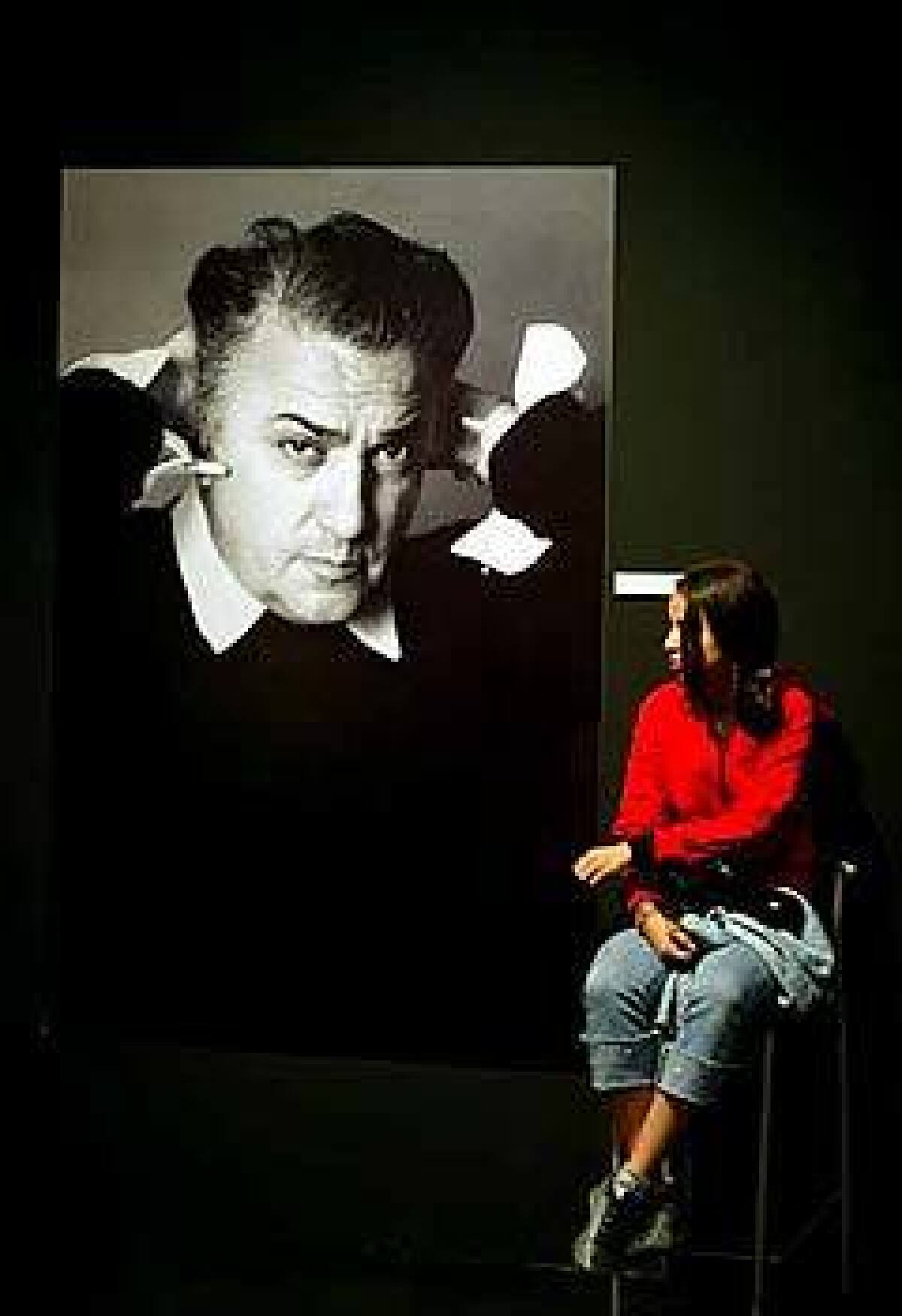

ROME — He was 18 and inexperienced — in all respects — when he came to Rome in 1938. For Federico Fellini, it was the beginning of a love affair that lasted more than 50 years.

Rome dazzled and indulged him. It fed the dreams he turned into such movies as “La Dolce Vita,” “8 1/2,” “Roma” and others so imaginative that a word had to be coined to describe them: “Fellini-esque.” He could hardly bear to be anywhere but Rome, even when Hollywood summoned him to receive an Oscar (four for best foreign film and an honorary award in 1993, just a few months before his death).

“When I was a boy, I wanted to travel and see the world,” he told Charlotte Chandler, the author of reminiscences titled “I, Fellini,” “but then I found Rome and found my world.”

The city has been marking the 10th anniversary of the director’s death this fall with “Romacord Fellini,” a celebration through the end of the year that includes concerts, presentations and showings of the master’s films. I went in October for the festivities and to see Rome through Fellini’s eyes, to sit in his favorite cafes and wander past the places from his films that lodged in my imagination: the Colosseum at night, lighted up like a birthday cake, as in “Roma”; the Bernini colonnade at St. Peter’s Square, where an errant young wife is reconciled with her husband at the end of “The White Sheik”; and, above all, Trevi Fountain, which some aficionados cannot conjure without envisioning Anita Ekberg and Marcello Mastroianni of “La Dolce Vita” wading in it.

To prepare for the trip, I spent most of my free nights for about a month watching videos: “La Strada” (1954), “Nights of Cabiria” (1957), “La Dolce Vita” (1960), “8 1/2” (1963), “Satyricon” (1969), “Roma” (1972), “Amarcord” (1974). Bizarre, vulgar, illogical, brimming with psychological disorder, Fellini’s films don’t submit easily to interpretation. Loving them is a visceral thing, a little like his love for Rome.

“FeFe,” Roman taxi drivers used to call to him, using the nickname by which he was known around the city, “why don’t you make pictures we can understand?” He says in “I, Fellini,” “I answer them that is it because I tell the truth, and the truth is never clear, while lies are quickly understood by everyone.”

It seems as though all of Rome knew Fellini. I met some of his old friends and colleagues almost effortlessly while I was here: Luigi Esposito, retired concierge at the Grand Hotel Plaza, who knew Fellini when he was sketching American GIs on the streets of the city during World War II to make money; and photographer Carlo Riccardi, who used to run into Fellini around town while taking pictures of people living the sweet life before Fellini’s film taught us to call it “La Dolce Vita.”

“He was a lovely man,” Esposito said. “Even when he was young, he was something.”

Filmmaking and fame

Fellini was tall and skinny when he came to Rome from his hometown of Rimini, too ashamed to wear swimming trunks at the beach in the nearby seaside town of Fregene, where he later bought a house and is remembered with an annual film festival.In his imagination, he looked more like suave, sexy Mastroianni, whom he cast as the lead in such autobiographical films as “8 1/2.” The director filled out and adopted accessories — tweed hat, brim turned down, and a coat, collar turned up — that created a look for him. As he aged, his eyebrows remained dark when his hair turned gray, and his bella figura increased in girth because he couldn’t resist pasta and pastry.

I frequently felt his presence. Walking the Pincio, a park on the northeast side of Rome, I fancied I saw him and his wife of 50 years, actress Giulietta Masina, on a dignified afternoon passeggiata. At the window of a shoe store on Via della Croce near the Spanish Steps, I wondered what FeFe would think of a certain pair of boots.

This section of Rome, stretching from about the Spanish Steps to the Piazza del Popolo, was Fellini’s neighborhood. He used to have coffee at Canova, a stylish cafe on the Piazza del Popolo, which he is said to have preferred to adjacent Caffè Rosati because Canova’s sidewalk tables were shaded from the morning sun.

Sandwiched between these, one on each side of the Via del Corso, are the almost-twin Baroque churches of Santa Maria dei Miracoli and Santa Maria di Monte Santo, designed in the 1660s by Carlo Rainaldi. Santa Maria del Popolo is across the way, justly more renowned for two Caravaggios depicting the crucifixion of St. Peter and the conversion of St. Paul, intimate images that could serve to remind us that, unlike many directors, Fellini took his inspiration from painting, not literature.

The piazza at the churches’ doorsteps is a terrific wide-open space, centered by an Egyptian obelisk, with steps leading up to a breathtaking overlook in the Pincio. The view of Rome from there is almost as good as in the opening scene of “La Dolce Vita,” which follows a helicopter carrying a statue of Jesus Christ over the Eternal City, dangling from a cable as if it were a toy action figure.

An excellent sampling of Roman humanity rushes across the Piazza del Popolo in plain view of an espresso drinker at Canova. “The show [in Italy] can be so engrossing that many people spend most of their lives just looking at it,” Luigi Barzini wrote in “The Italians.” Fellini was a great people watcher and collector; it stimulated his thinking about the characters in his films. He often drew people who interested him on napkins and tablecloths — fat, ugly, grizzled, dwarfish, the odder the better and, if female, magnanimously endowed.

Along with filmmaking, pasta, the circus and dreams, women are what Fellini adored most. It was part Italian machismo, part rebellion against the Catholic faith in which he was raised and part mother love, as evidenced by his fascination with big breasts. Fellini’s sexism struck me as more sexy than sexist, a quality often missed by tourists flocking to the chaste Vatican and Forum.

I felt it all around his neighborhood, where some of Rome’s ritziest shops cluster. On Via del Babuino, near Fellini’s apartment, a woman can buy a negligee to match her sheets, and on chic Via dei Condotti, running from the foot of the Spanish Steps to Via del Corso, there are costly gifts for lovers from La Perla, Max Mara, Dolce & Gabbana. In “I, Fellini,” the director told author Chandler something that echoed in my mind about rich men taking their mistresses shopping there in the afternoon: “After that, they go to the ‘nest,’ and the man is finished in time to arrive home for dinner with his wife and children.”

Regardless of where he’d been, Fellini went home to elfish Giulietta, his soul mate and muse. Her performance in “La Strada” as the heart-rending clown Gelsomina, opposite a savage circus strongman played by Anthony Quinn, helped make Fellini famous. He loved the privacy of their life together. In his brief 1993 Oscar acceptance speech, he brought down the house by saying, “Thank you, dearest Giulietta. And please, stop crying.” At the end of his funeral in Michelangelo’s church of Santa Maria degli Angeli, near the Piazza della Repubblica, she did the same, waving and saying simply, “Ciao, amore.” She died of cancer five months later.

They lived at No. 110 Via Margutta, an apartment marked by a simple plaque, on a pretty Roman lane close to the Piazza del Popolo. Artists and antiques dealers have long favored this street, which has a few restaurants and hotels but is otherwise residential.

Nearby, the Grand Hotel Plaza on Via del Corso, where I stayed for several nights, is another important stop for Fellini pilgrims. From his childhood, the director was in awe of grand hotels where beautiful rich people drank champagne. With its fabulously frescoed inner lobby and marble staircase guarded by a large stone lion, the Plaza evokes Fellini’s grand hotel fantasies.

My room on the third floor was pure Italian baronial. There were prints of Rome on the walls, tassels, fringed lamps, a generous double bed and flowingly draped casement windows, all with the look of a beautiful Roman woman of a certain age who’s barely hanging on to her looks.

When Fellini found fame, he could afford to entertain American producers here. “They spend their days sitting in their underpants in the biggest suites making long-distance calls,” he says in “I, Fellini.” “ When they receive you they make no effort to put on anything more.”

Real-life setting

Fellini found shooting on location hard to control and had elaborate re-creations of famous Roman monuments — Trevi Fountain, for instance — created at Cinecittà, the studios on the southern outskirts of the city that became virtually synonymous with him. It isn’t easy for Fellini fans to visit the places where key scenes from his movies were filmed.But you can take the Metropolitana from Piazza del Popolo to Cinecittà, as he routinely did. He went there even when he wasn’t making a picture to get inspiration and feed the studio’s stray cats.

Riding the subway is a Fellini-esque trip in itself, evoking an unforgettable sequence in “Roma,” the director’s paean to the Eternal City, depicting the construction of the Metropolitana. In it, workers break through a wall underground and discover an ancient Roman house with breathtakingly intact wall frescoes, like those tourists see at the National Roman Museum in the Palazzo, that melt away before our horrified eyes.

In 30 minutes, you’re at the front gate of Cinecittà, though you can’t go in unless you’ve come to make a movie (a pity, because Fellini’s office is still there, the colored markers he sketched with on the desk, his hat and scarf hanging from a peg on the wall). But for devotees, the 99-acre studio complex is still worth a visit. It looks like an Italian Fascist Art Deco college campus, overhung by funereal cypresses. It was built in the 1930s by Benito Mussolini and used for such big American movies as “Ben-Hur” (1959) and “Cleopatra” (1963) during the decade after the war when the paparazzi chased U.S. stars up and down the Via Veneto and Rome got the moniker “Hollywood on the Tiber.”

Flush times didn’t last, and Cinecittà moldered; eventually part of it was sold to developers of Cinecittà Due, a big shopping mall. But somewhere FeFe is smiling because in the decade after his death, Cinecittà came back to life, attracting American movie projects again, including Martin Scorsese’s “Gangs of New York” and Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of Christ” (due in early 2004).

Beyond Cinecittà, Canova, Via Margutta and the Grand Hotel Plaza, Fellini devotees must rely on the imagination to guide them. For summoning up “La Dolce Vita,” a movie that fascinated and repulsed viewers, visits to Via Veneto and the Trevi Fountain are musts.

The Veneto fell on hard times in the 1980s and 1990s, but it’s starting to look up, with swank idlers again filling Harry’s Bar, Doney and the Café de Paris. And crowds never forsook the 18th century Baroque fountain, a looming white marble confection with water so clear and inviting some people can’t resist plunging in à la Ekberg and Mastroianni.

Just off the little piazza, on Vicolo delle Bollette, is Al Moro, a trattoria favored by Fellini, known for its version of spaghetti alla carbonara. The director liked proprietor Mario Romagnoli’s face, which appears in a large photograph in the front room, and cast him in “Satyricon.”

One night, I took a taxi to Trastevere, on the west side of the Tiber River, to tour the International Museum of Film and Entertainment, a funny little place on Via Portuense way off the beaten track that tries its best to live up to its name. It is stuffed with Italian film, TV and theater memorabilia, including scripts and letters written by Fellini.

Then, in a flash of enlightenment, I knew what next to do to celebrate Fellini. I saw a movie at the Alcazar, one of the many theaters in Trastevere: Bernardo Bertolucci’s “The Dreamers,” about a youthful ménage a trois, which I found ultimately tiresome. It didn’t matter, though. I was in a bigger, better motion picture: Fellini’s Rome.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.