Postcards From the West: In San Antonio, remembering (and rethinking) the Alamo

The Alamo has captured the imagination since the bloody 1836 battle there. Sift the myths from the history at the shrine, then amble over to the nearby River Walk for another chapter in San Antonio’s story.

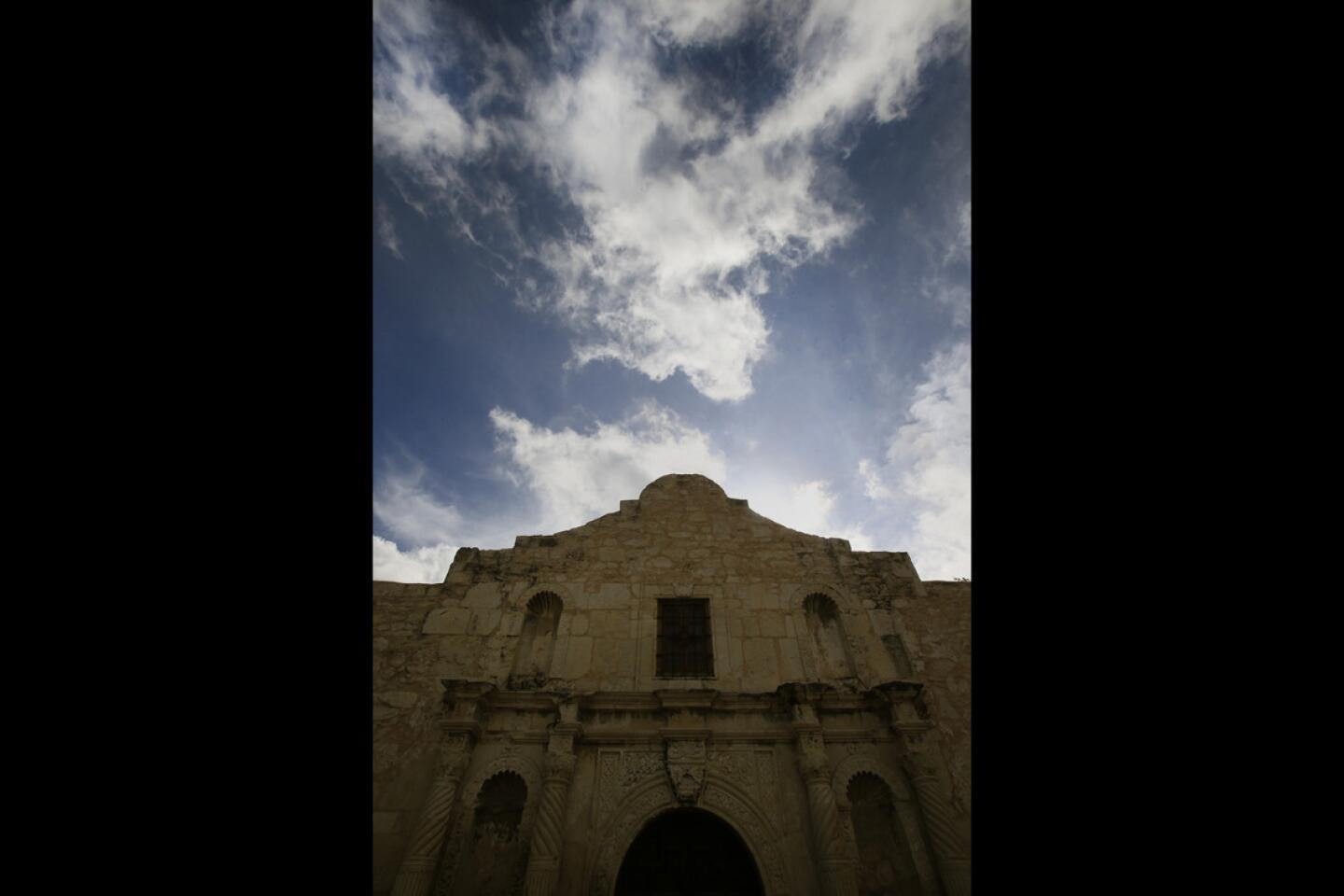

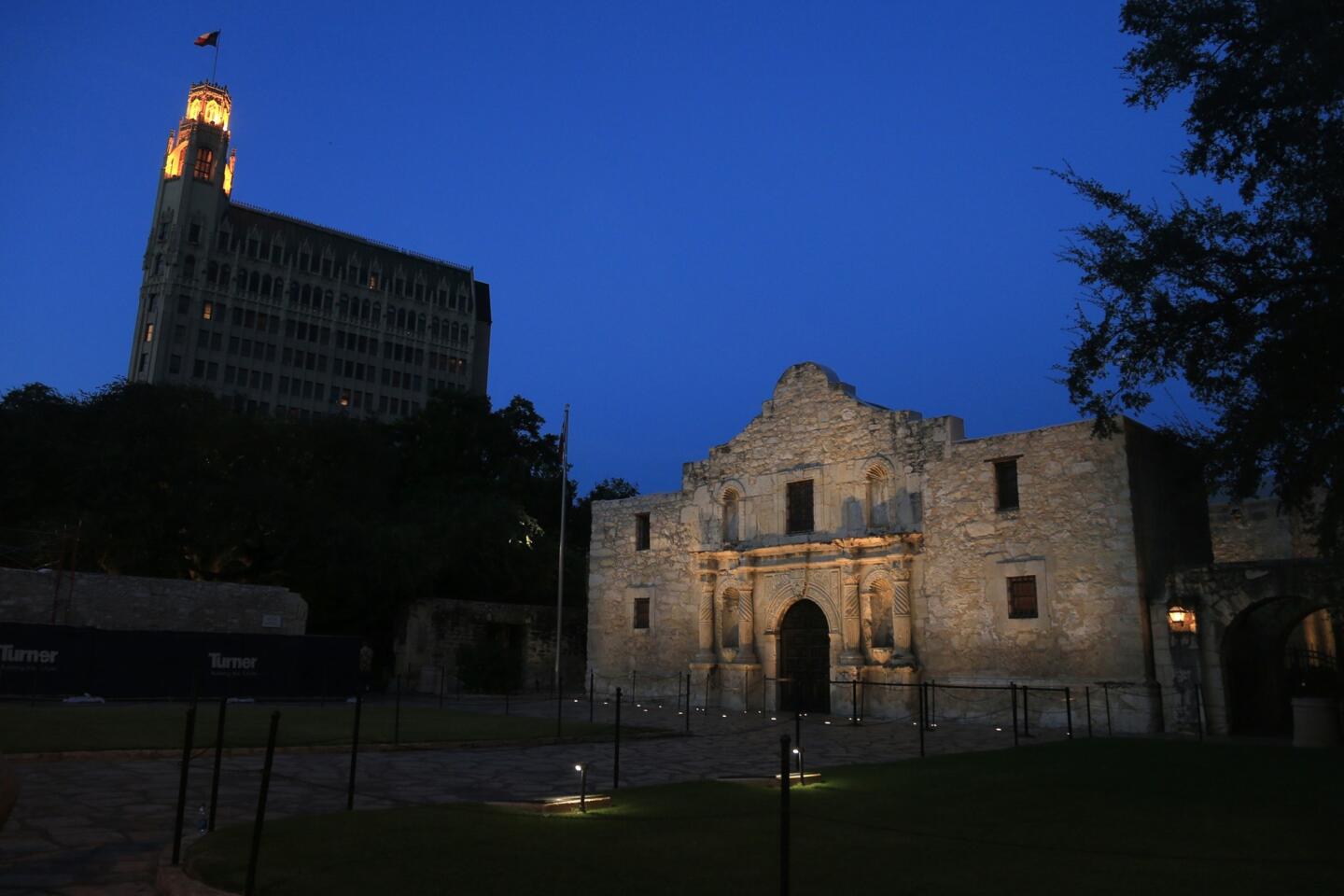

Reporting from SAN ANTONIO — The most famous building in Texas is smaller than you expect, and it’s about as pretty as your average California mission. In fact, it was once a mission, though these days it stands across the street from an unholy row of Ripley’s and Guinness tourist operations. You can cover it in about two hours.

Yes, it’s the Alamo. And yes, it’s worth remembering — and maybe some rethinking too.

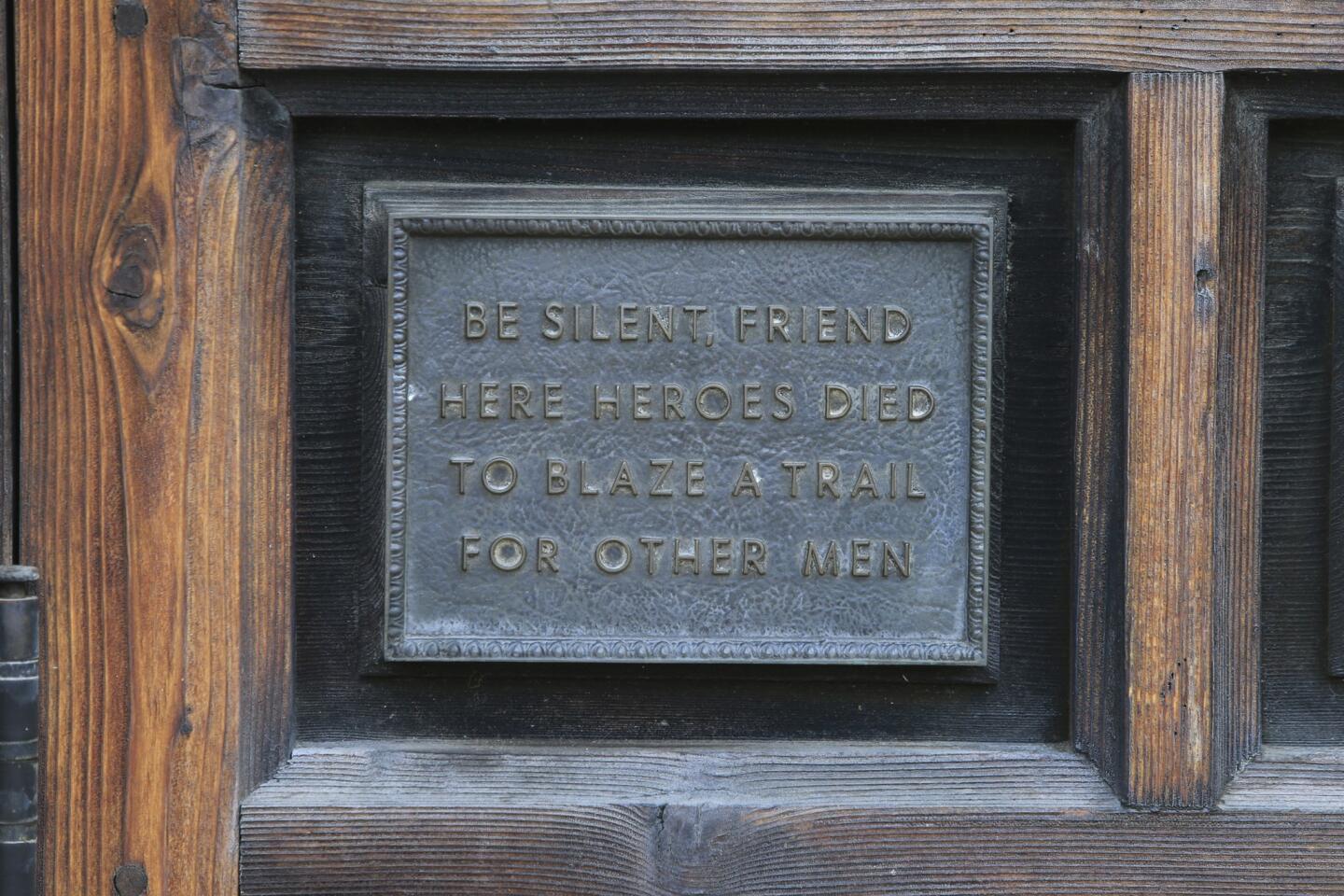

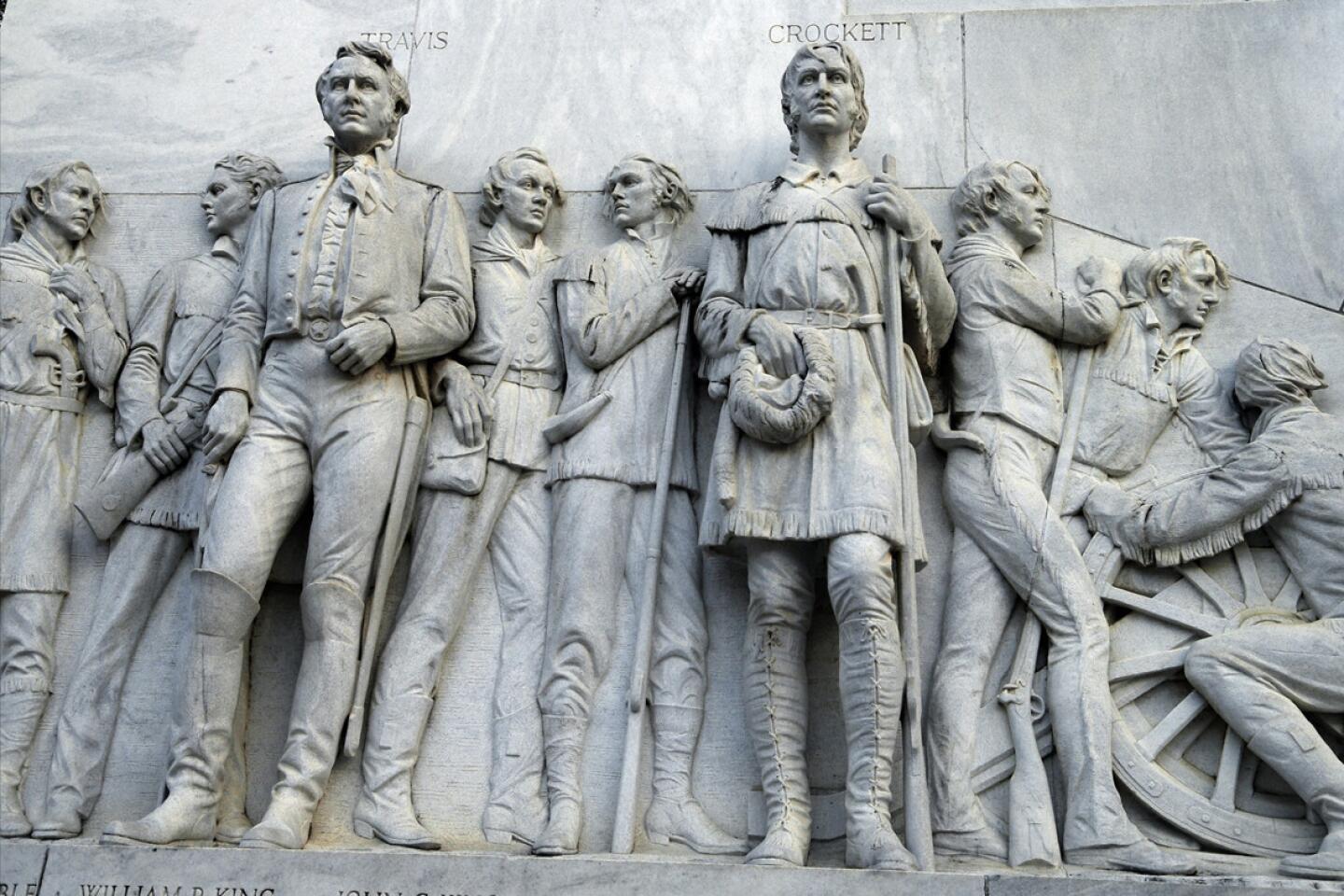

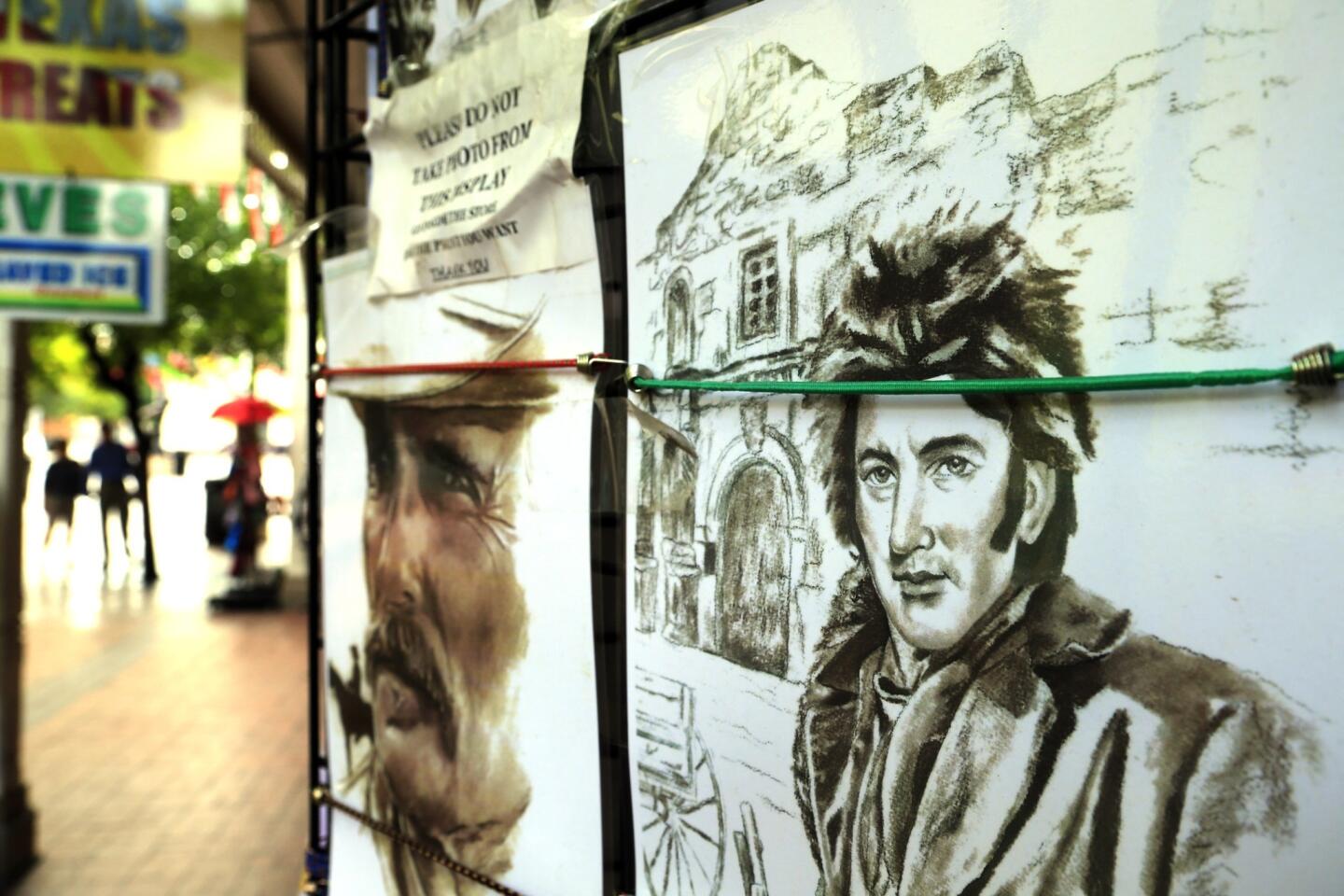

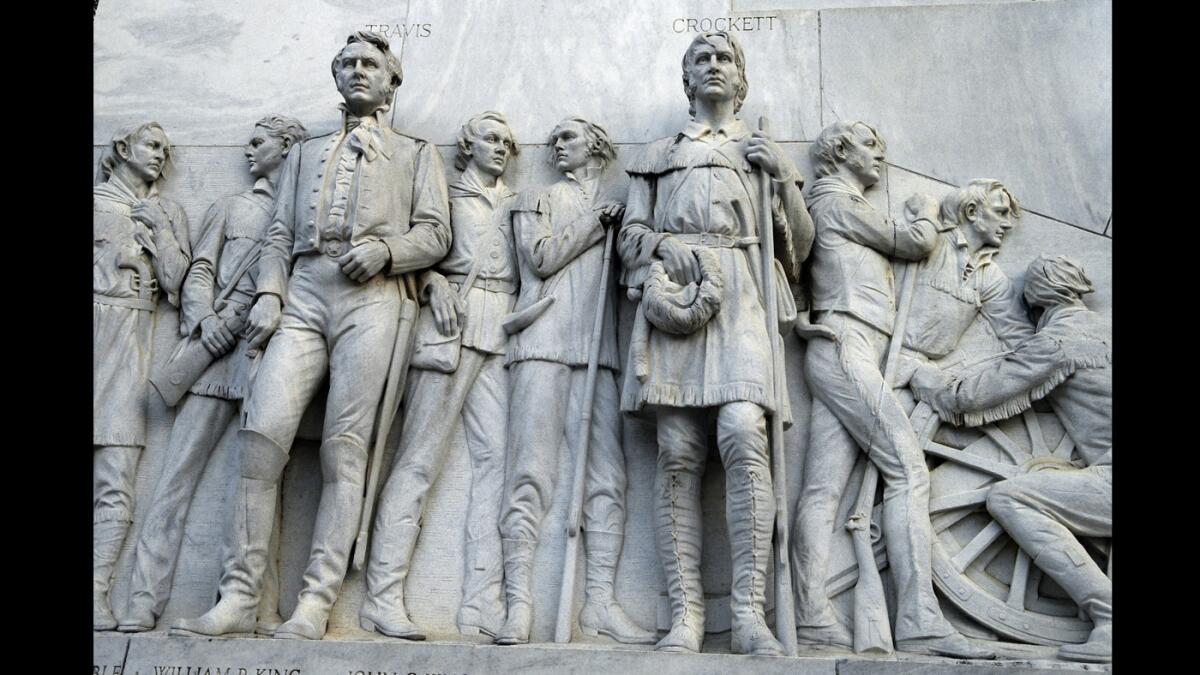

This is where William Travis, David “Davy” Crockett, Jim Bowie and about 200 other rebels died fighting for Texas sovereignty against a Mexican force of perhaps 1,800 soldiers, perhaps 6,000. Ever since that day in 1836, statesmen, stateswomen and storytellers have embraced the Alamo as a symbol of doomed bravery.

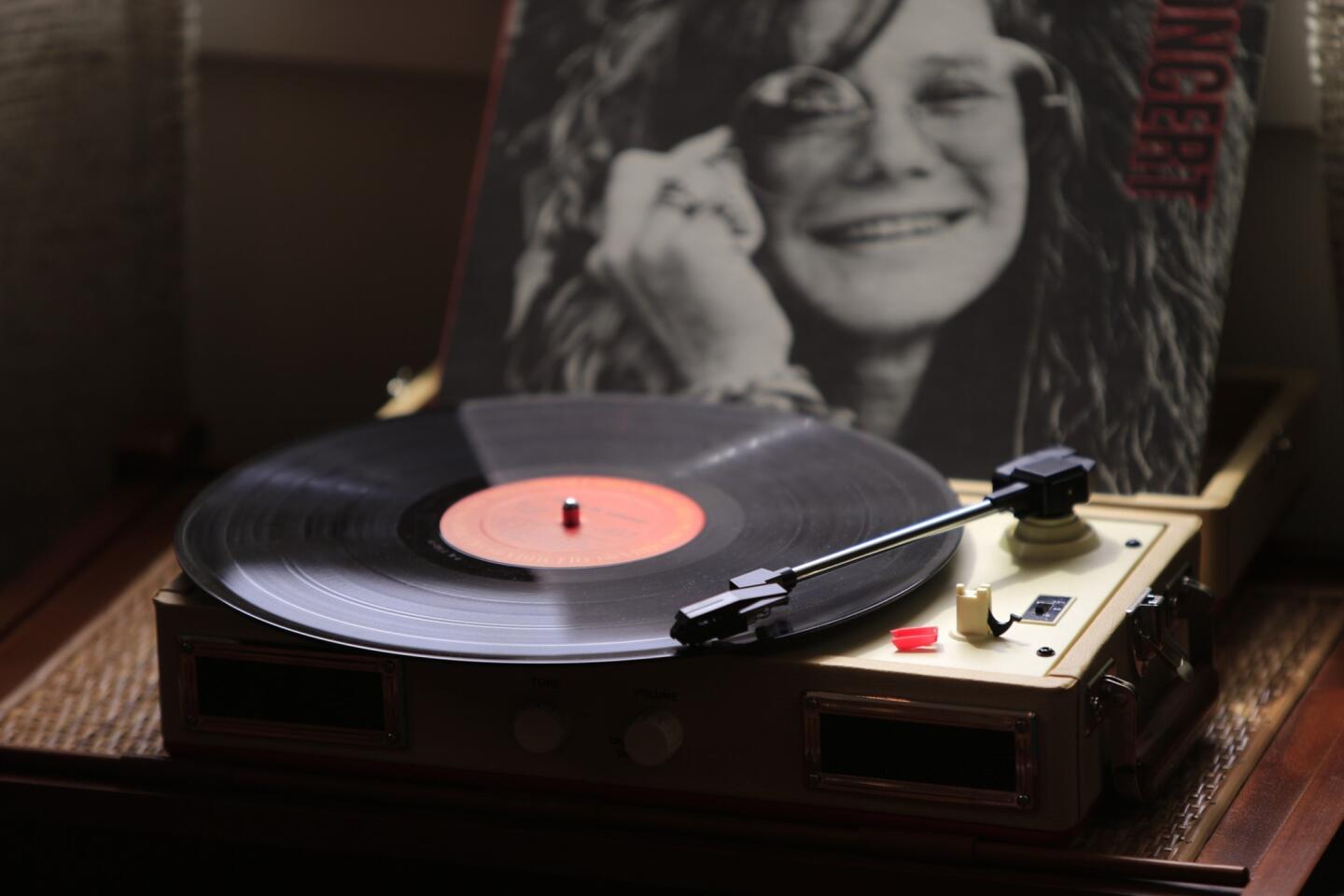

The story won over Fess Parker, who starred in a ‘50s Disney miniseries about Crockett, and John Wayne, who directed and starred in a movie version of the Alamo story in 1960. And it spoke to pop star Phil Collins, who grew up in England watching Parker on TV. He spent a fortune acquiring 200 artifacts of the battle and of Texas history, then last month handed them over to the state of Texas.

The Collins collection includes letters from Travis, a rifle of Crockett’s, a knife of Bowie’s and a sword that belonged to Mexican leader Antonio López de Santa Anna. State officials hope to build a museum to show it all off, but no new building will displace the Alamo’s facade as an emblem of the West.

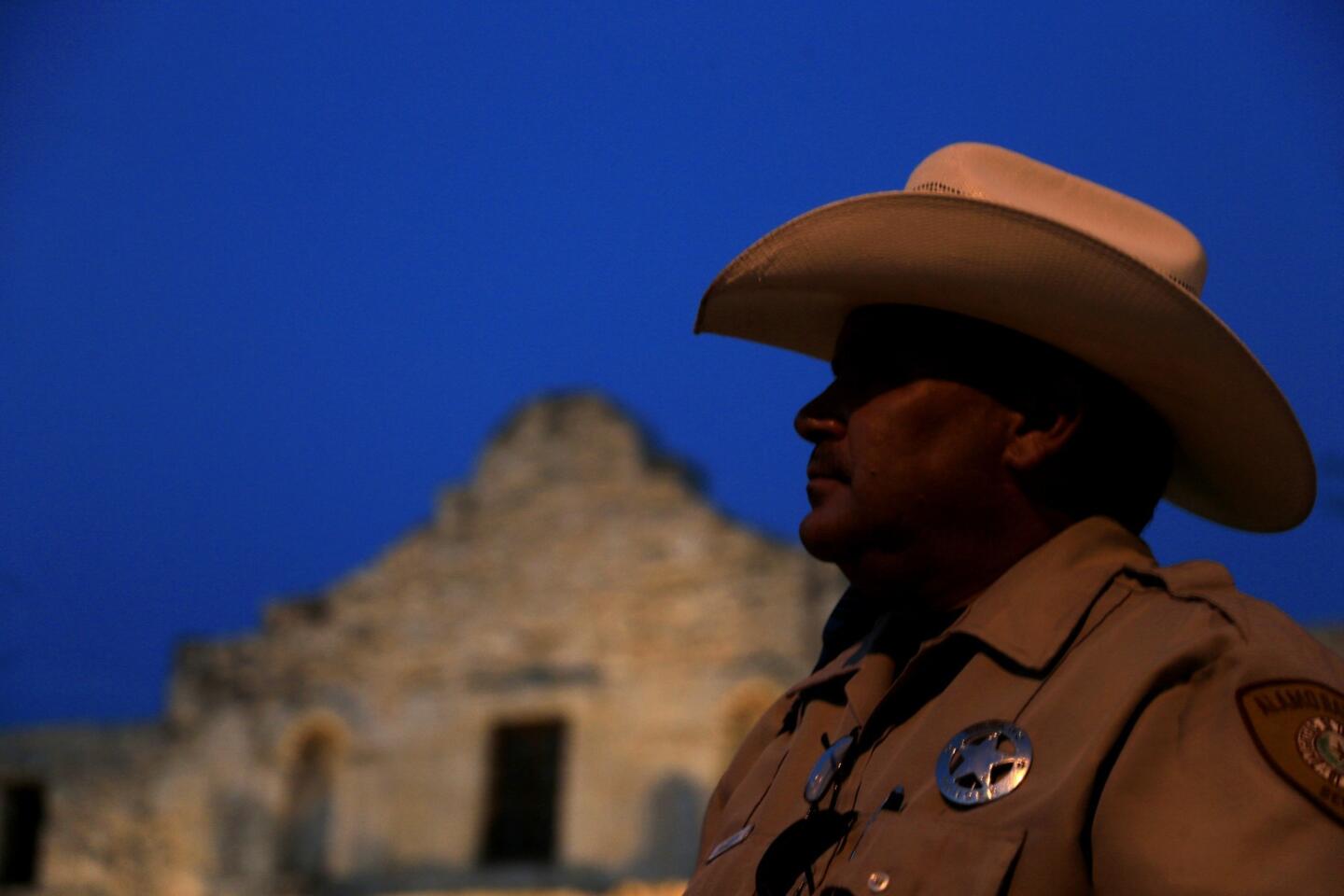

This made it a natural stop for Times photographer Mark Boster and me on our campaign to explore some of the West’s most enduring icons. We spent three fall days in San Antonio, sifting history and myth, nosing around mission ruins, roaming the River Walk and admiring landmarks that turn out, like the Alamo, to be old buildings in their second lives.

First stop was the remnants of the old Alamo compound, much of which was gobbled up by shops and streets in San Antonio’s early decades. Nowadays, the landmark, which is free to visit, is surrounded by urban San Antonio and dwarfed by the tall, slender Emily Morgan Hotel to the north and the low, rambling Menger Hotel to the south.

You begin with the Alamo’s focal point, the former church with the weathered facade that’s now known as the shrine of Texas liberty. It was built by Spanish missionaries and Coahuiltecan Indians in the 18th century as the chapel of the Mission San Antonio de Valero. But the mission didn’t last, so the roofless building was pressed into service as a garrison for Spanish troops, then Mexican troops and then, in 1836, a band of rebels aiming to pry Texas from Mexico and establish a republic.

Inside the shrine, gentlemen are instructed to remove their hats. In dim light, visitors inspect a knife associated with Bowie, a vest that belonged to Crockett and a row of flags that honor the dead rebels. Many of them had recently arrived from Tennessee and elsewhere (including former Tennessee congressman Crockett); most expected to be paid for their services with big chunks of land; and many had not-so-heroic histories (including the slave-trading knife-fighter Bowie, who was sick in bed when the battle took place). But there’s no denying the extremity of their last chapter, holed up in the ruined mission compound for 13 days as enemy troops massed nearby.

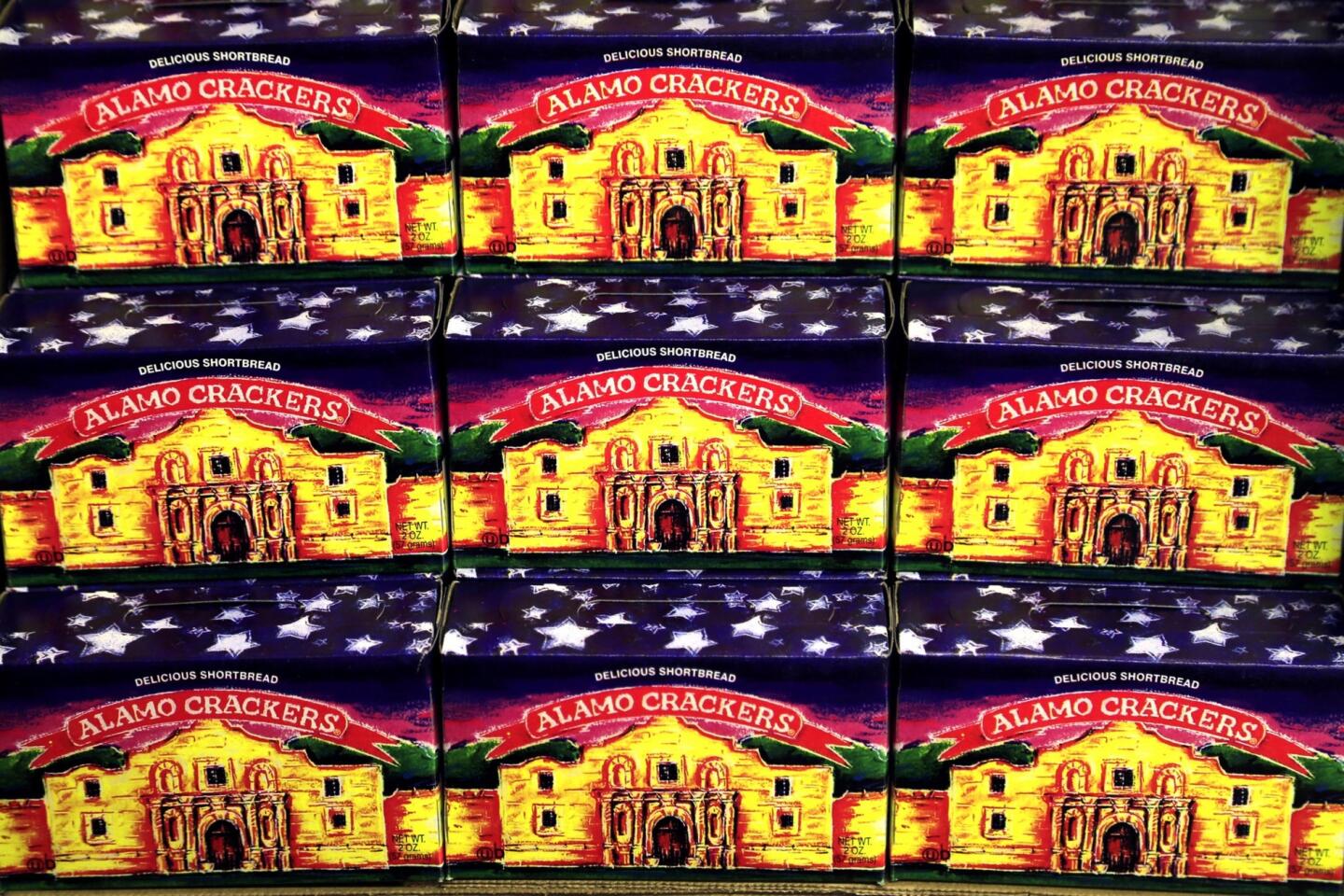

Nowadays, the shrine has a solid roof over it, a gift shop next door (faux coonskin caps, $12.99) and a well-tended garden all around. But as you wander through the shrine, or linger by the neighboring long barracks building (which was closed for improvements during my visit but houses a collection of Alamo artifacts), it’s not hard to imagine the scene.

“This is where Texas begins,” I heard somebody say with an accent I couldn’t immediately place. It was Dennis Kozinski, who had come to town from his native Ukraine. He was sporting cowboy boots and a silver belt buckle — but he was thinking about the Ukrainian troops, outnumbered along the Russian border in recent months.

“It’s like Ukraine,” he said of the Alamo battle. “Before this moment, they were not sure. But this moment, being against 5,000 Mexicans, they were sure. Being against all that, it brings them together.”

“Victory or death,” Travis, the rebels’ commander, wrote in a letter seeking reinforcements during the siege. But reinforcements never came, or at least not enough to make a difference. When Santa Anna’s troops charged on March 6 — with orders to take no prisoners — the rebels did what they could with cannons, muskets and swords, killing as many as 600 of the attackers. But it was over quickly.

By most accounts, every rebel fighter was killed that morning. But the recollections of surviving women, children, slaves and Mexican soldiers were hazy and often conflicting, leaving historians to endlessly debate who died when, where and how. Some people believe the Alamo defenders’ ashes are at nearby San Fernando Cathedral; many don’t.

This much is clear, though: Six weeks later, revenge-seeking rebels prevailed in the Battle of San Jacinto, took Santa Anna prisoner and proclaimed Texas a republic. Nine years later, the U.S. annexed Texas. Twelve years later, in 1848, the U.S. won the Mexican-American War.

To see what San Antonio has been up to since then, just look around Alamo Plaza, where you’ll see stately buildings from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, some of them now occupied or neighbored by Ripley’s and Guinness.

Activists at the Alamo Plaza Project would like to replace these businesses with a replica of the Alamo’s western wall, which once stood there. Richard Bruce Winders, historian and curator of the Alamo, told me the block “presents a sort of problem for the Alamo.” But, he continued, “This is America. Do we drive people out of buildings just because we want the buildings? I’m not comfortable with that.” (Earlier this year, the San Antonio City Council named an Alamo Plaza advisory committee to wrestle with the issue.)

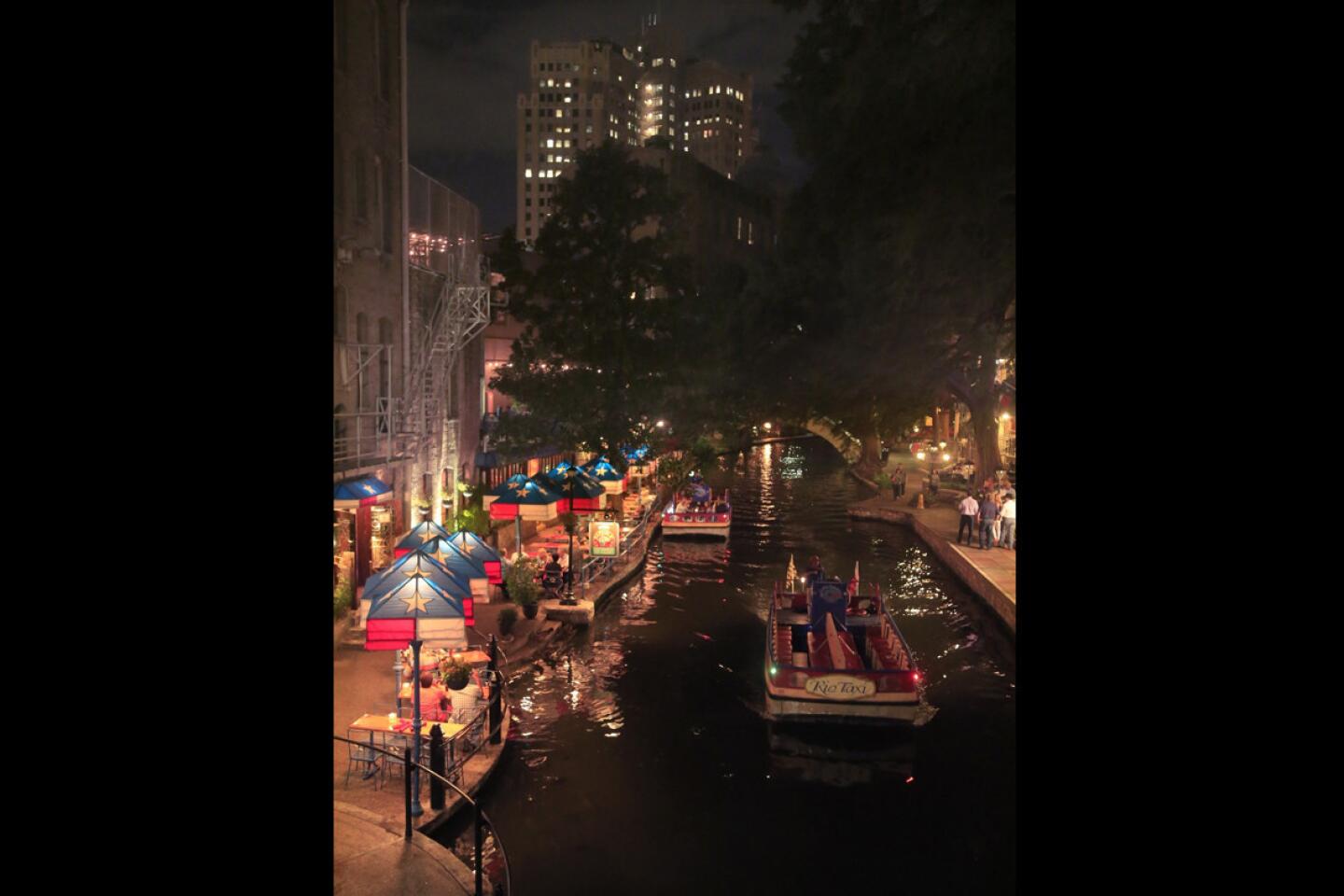

I sidestepped the sideshow businesses because I wanted more time with a San Antonio tourist attraction far bigger than I expected — the River Walk.

Conceived in 1929 by architect Robert H. H. Hugman and completed (or so it seemed) in 1941, the River Walk was a simple idea: Put walkways along the banks of the San Antonio River as it loops through downtown and make them a thoroughfare for tourists.

It worked. Then the system got a boost in the 1960s, when San Antonio hosted HemisFair ’68. Further boosts followed, and the walkways now line 15 miles of the river. Scores of restaurants and hotels stand alongside the river, as do the city’s glittering new Tobin Center for the Performing Arts (which incorporates the facade of the old municipal auditorium); the San Antonio Museum of Art (built in the 1980s on the site of the old Lone Star Brewery) and the restaurants and shops of the not-quite-completed Pearl (another brewery redevelopment project).

As many a conventioneer has discovered, you can spend three days meandering the River Walk and scarcely set foot on the grittier downtown streets where locals tread.

My plan was to rent a bike and pedal to the four other missions along the river within an easy ride of the Alamo — but rain came. So we drove mission to mission, walking grounds maintained by the National Park Service and interiors where Catholic priests still say Mass.

If history had happened a bit differently, I thought, any one of these ruins might be a shrine to Texas liberty. The Alamo might be a working church or a brewery. Or part of Mexico.

Later that night, when I doubled back downtown and found the old Alamo shrine bathed in floodlights, backed by storm clouds, surrounded by rain puddles, it didn’t look so small after all.

::

A timeline of the Alamo and Texas history

1521

Spain sets about claiming much of North America, including land that is now Texas.

1744

Spanish Catholic missionaries lay a foundation stone for Mission San Antonio de Valero, later known as the Alamo. The church and neighboring buildings stand near the San Antonio River in what is now downtown San Antonio.

1773

San Antonio becomes capital of Spanish Texas.

1793

The padres give up at Mission San Antonio de Valero, and the complex is secularized. The convento, a long building neighboring the church, becomes a barracks for Spanish troops.

1803

New troops occupy the mission site and stay for decades, first as soldiers for Spain, later as soldiers for Mexico. The landmark becomes known as the Pueblo de la Compañia del Alamo. But people eventually start calling it the Alamo.

1821

Texas becomes part of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas.

1823

Mexican leaders, eager to boost the area’s population, encourage white settlers to start a colony in the San Antonio area. Over five years, more than 25,000 settlers show up.

1835

Texas colonists — mostly whites from the United States — launch a War of Independence against Mexico. San Antonio (population about 2,500) becomes a key location. The rebelling colonists, known as Texians, take control of the Alamo and the town.

February 1836

Mexican leader Antonio López de Santa Anna and thousands of troops arrive. The Texas rebels take over the Alamo while Mexican forces mass across the river.

March 1836

About 200 troops dig in at the Alamo, including William Travis, James Bowie and David “Davy” Crockett, along with some women, children and slaves. After a 13-day siege, Mexican troops attack on the morning of March 6, overwhelm the Texas rebels and kill almost all the men.

April 1836

About 220 miles east of San Antonio, Gen. Sam Houston leads Texas rebel forces into the Battle of San Jacinto, with shouts of “Remember the Alamo!” resounding. The rebels kill more than 600 Mexican soldiers and capture more than 700, including Santa Anna.

1845

Congress authorizes a resolution to bring Texas into the U.S. as the 28th state. Soon after, the Mexican-American War begins.

1848

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ends the Mexican-American War, gives the U.S. about half of Mexico’s territory and makes Texas an uncontested American state for the first time.

1850

The U.S. Army leases the Alamo, rebuilds its stone church and adds a roof for the first time. The new roof requires addition of a curved parapet — the birth of the Alamo’s hump.

1870s

The Alamo compound is divided up and sold. Some of the property reverts to the Catholic Church.

1883

Texas buys the Alamo church from the Catholic Church for $20,000. The long barracks is a general store.

1903

As plans are laid to level the long barracks and build a hotel, local teacher and preservationist Adina de Zavala starts a campaign to save the building and enlists wealthy rancher Clara Driscoll. They buy the Alamo church and the long barracks building and hand it over to the Daughters of the Republic of Texas.

1905

The Daughters hand ownership of the site to the state. The state entrusts the Daughters to be caretakers of the church and long barracks as “a shrine to Texas liberty.”

1911

The first movie about the Alamo, “The Immortal Alamo,” is released. No known copies remain.

1914

Release of “The Siege and Fall of the Alamo,” a silent feature film shot on site with 2,000 extras.

1935

As the battle’s centennial nears, the Alamo complex is renovated and expanded, including a gift shop. Later in the decade, a 60-cenotaph is added in front of the Alamo site, honoring those who died in the battle.

1954

“Davy Crockett,” a five-part Disney miniseries, airs on TV. Fess Parker stars.

1960

“The Alamo,” a film directed by and starring John Wayne, is released to wide acclaim despite historical accuracies.

That same year, hoping to quietly slip away from the landmark during a presidential campaign stop, John F. Kennedy asks to be steered to the rear exit. “There is no back door,” San Antonio attorney Maury Maverick Jr., replied. “That’s why they were all heroes.”

1968

The daughters of the Republic of Texas open a museum in the Long Barracks building.

1985

Acting on a psychic’s tip that his stolen bicycle is in the Alamo basement, Pee-wee Herman takes a tour in the film “Pee-wee’s Big Adventure” --only to be humiliated by the tour guide’s reply that there is no basement.

2004

“The Alamo,” directed by John Lee Hancock with Billy Bob Thornton as Crockett, is slammed by critics.

2011-12

A state investigation finds that the Daughters of the Republic of Texas have “failed to adequately preserve and maintain the Alamo,” misused state funds and failed to follow their own rules. The Legislature gives the Texas General Land Office greater control of the landmark, though the Daughters remain in charge of daily operations.

2014

English musician Phil Collins donates more than 200 Alamo-related artifacts and documents to Texas. It’s billed as the largest collection of its kind.

Sources: The Alamo, thealamo.org; the National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary, https://www.1.usa.gov/1qmi9TC; San Antonio Mission National Historical Park, https://www.nps.gov/saan; Texas State Historical Assn., https://www.bit.ly/10jWV1O; Internet Movie Database, https://www.imdb.com

::

24 hours in Austin? Tex-Mex, music and history

Three facts about Austin, Texas:

— It’s 80 miles from San Antonio.

— LAX-Austin flights are often cheaper than LAX-San Antonio flights.

— Austin is fun.

OK, maybe that’s two facts and one widely held opinion. If you can get to Austin when the city’s prices and population are not inflated by the annual South by Southwest festival of music, film and interactive media (March 13-22, https://www.sxsw.com), you’ll see, hear and taste plenty of rewards. Live music. Tex-Mex and barbecue. All the energy that comes with a 52,000-student University of Texas campus.

I capped my September trip to San Antonio with about 24 hours in Austin, so I can recommend these spots:

Güero’s Taco Bar (1412 S. Congress Ave.; [512] 447-7688, https://www.guerostacobar.com), a bric-a-brac-filled Tex-Mex restaurant, seems as casual, smart and rowdy as Austin itself. The weathered wood floor dates to the building’s days as a 19th century seed and feed store (with dice games in back and bookies on the porch, it is said). Dinner main courses $7.99-$12.99.

The Continental Club (1315 S. Congress Ave.; [512] 441-2444, https://www.continentalclub.com) is the granddaddy of live-music joints in the city, dating to 1957. In the dim confines, you’ll see an endless parade of live musical acts — typically three or more per night, every night. Cover prices vary.

If you can’t afford the hippest, priciest most central hotels (for instance, Hotel Saint Cecilia, Hotel San José, Kimber Modern), you can still find style on the brink of suburbia. The Lone Star Court (10901 Domain Drive; [512] 814-2625, https://www.lonestarcourt.com), which opened in 2013 about 12 miles north of South Congress Avenue, is full of playful flourishes from fire rings to farm equipment. Also live music Wednesdays through Sundays. Doubles generally $169-$249.

The LBJ Presidential Library (2313 Red River St.; [512] 721-02000, https://www.lbjlibrary.org), housed in a brutal minimalist building on the UT campus, tells the story of Lyndon Baines Johnson (1908-1973) and serves up an interesting slice of the ‘60s. (LBJ was president from late 1963 to early 1969.) On the gift shop wall, don’t miss the great 1968 photo of the dog-loving president howling along with his mutt, Yuki, while his toddler grandson, Patrick, watches in wonder. Adult admission $8.

If I’d had four more hours, I would have headed for Franklin Barbecue (900 E. 11th St.; https://www.franklinbarbecue.com), whose praises have been sung by Texas Monthly and Bon Appétit magazines, among others. Then I’d have jumped into the Barton Springs Pool, the city’s favorite swimming hole, in Zilker Metropolitan Park.

::

Separating the fiction from the fact at the Alamo

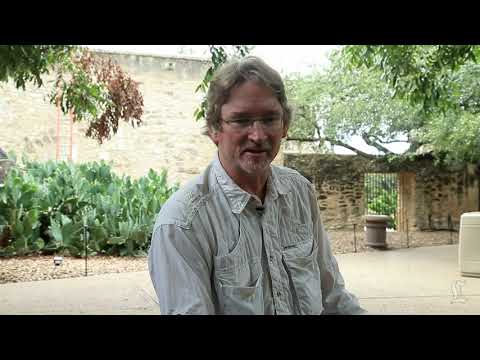

You thought the fighting was over at the Alamo. But only now, 178 years after the last cannon blast, is Richard Bruce Winders gaining the upper hand.

Winders, 61, has been historian and curator of the Alamo since 1996. From the start, his job has been complicated by the legacies of Fess Parker and John Wayne, who each played Davy Crockett in not strictly accurate stories of the Old West.

When he started in the job, Winders recalled, separating fact from fiction “was much more difficult” because “the majority of visitors had seen Fess Parker’s portrayal of David Crockett [on television in the 1950s] or had seen John Wayne’s movie,” which was released in 1960.

Nowadays, Winders said, fewer visitors have seen those Hollywood treatments. And that gives him a better chance of gently guiding them toward a more historical version of the story.

Since earning a doctorate in history from Texas Christian University in 1994, Winders has written several books about 19th century Mexico and the Republic of Texas, which declared itself in 1836 and was absorbed by the United States in 1845.

In “Sacrificed at the Alamo: Tragedy and Triumph in the Texas Revolution” (State House Press, 2004), Winders thinks that infighting among revolutionary troops was a key reason that reinforcements never arrived to aid the Alamo.

In daily conversations at the landmark, he likes to point out that “the Texas Republic is something that happened in the course of a long Mexican Civil War.”

Winders, who spent many years as a classroom teacher, is not above donning period attire to dramatize the story in living history presentations at the shrine. And he knows he’s playing to a broad audience, including Texans who studied their state’s history in seventh grade, other Americans who know only the broad outlines of the tale, and foreigners who “often know more about the story of the Alamo than Americans or native Texans.”

Still, a big chunk of the Alamo’s 3 million annual visitors arrive certain that the landmark’s facade had its distinctive hump, or parapet, in 1836 and, of course, a roof too. They often imagine that the final battle happened in daylight and that it was all Americans on one side and all Mexicans on the other. And they may assume that with 189 confirmed rebel deaths, the Alamo battle must have been the deadliest day Texas troops suffered in their fight for independence.

No, no, no and no, Winders tells them gently.

The U.S. Army added the Alamo church’s roof and hump in 1850. The battle began before dawn and was probably over in about 90 minutes. Alongside the scores of doomed defenders of the Alamo who had come from other places (many from Tennessee), several were native Texans (Tejanos) with names such as Abamillo, Badillo, Espalier and Esparza. And three weeks after the Alamo battle, Mexican troops executed more than 300 prisoners in the Goliad Massacre.

In fact, when the Texas troops got their revenge at the Battle of San Jacinto in April 1836, many sources say they were hollering both “Remember the Alamo!” and “Remember Goliad!”

Said Winders: “The worst way to educate somebody is to say, ‘Everything you know is old, everything you know is stupid.’

“What you want to be able to do is introduce people to things that make sense.”

Twitter: @mrcsreynolds

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.