A Second Renaissance in Harlem

NEW YORK — Noisy, diesel-belching tour buses routinely roll uptown headed for the heart of Harlem. Some residents call them “drive-bys.”

“The bus comes by. Cameras go off. Then they’re gone,” said Anthony Bowman, co-owner of the Harlem Gift Shop. “There’s no exchange if you only roll off a bus.”

The exchange, as Bowman called it, is a deeper interaction with Harlem and its people. The neighborhood, covering much of the north end of Manhattan above Central Park, isn’t on the itinerary of many tourists. But it’s one of New York City’s most rewarding spots, a community where America’s past, present and future are all dramatically represented. Walking tours--on your own or with a guide--allow you to take in a treasure trove of history while day-to-day life pulses around you.

Named by early Dutch settlers, Harlem had few black residents until a wave of white flight at the beginning of the 20th century--the product of failed real estate speculation, a growing black presence and a frustrating wait for a rail line connecting to lower Manhattan. The Great Migration of the late 19th century drew thousands of Southern blacks to New York, and black real estate agents steered clients to Harlem.

The neighborhood became the heart of the 1920s Negro Renaissance, a social movement that wed art and activism. As a center of urban black America, it was home to churches, hospitals and other important institutions.

Harlem was a mecca for black activists, intellectuals, painters and musicians. Writers Langston Hughes, Nella Larsen and Zora Neale Hurston and political figures Adam Clayton Powell Jr., Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X are among those whose contributions are memorialized in buildings, parks, housing projects and street names throughout the neighborhood.

Today the area’s architectural grandeur rubs elbows with scaffolding announcing gentrification, as well as boarded-up, burned-out emblems of past neglect. The arrival of Bill Clinton, who set up an office on 125th Street last year, coincided with a burst of public and private development that put Harlem in the spotlight again. A smattering of new cafes, galleries, gift shops and boutique hotels signals a percolating tourist industry.

When I was a child living in suburban Washington, D.C., Harlem was a place where I visited relatives. Faded family snapshots capture Aunts Anne and Skeeter and Uncles Bud and Ty helping me grow up back when. These same relatives put me up in 1988 when, as a Harvard graduate student, I started field research on gentrification in Harlem.

But visiting as a tourist was to be something different. This time, a high-school friend’s 40th birthday party in February brought me to New York. The invitation’s hotel suggestions included one that caught my eye: the Harlem Flophouse, a 11/2-year-old boutique hotel on 123rd Street. I booked myself for a weekend stay, and Demetra, a friend from Maine, joined me on her first Harlem visit.

The Harlem Flophouse is run by René Calvo, a writer from Massachusetts who has lived in New York for 15 years. Tucked between 7th and 8th avenues, the three-room hotel is in the heart of Harlem. The house, a four-story 1890s brownstone, was in the throes of restoration during our stay. Calvo, who is still searching for the right Victorian-era wallpaper, said he wants to restore the building’s grandeur without erasing its “torrid past.”

“Beautiful and rough around the edges, a little funky,” is how he described the place in a conversation after my visit. A parlor with two kitschy orange sofas and a fireplace opens out to the kitchen on the spacious first floor, where guests relax, socialize and soak in Latin jazz. In a quirky nod to the brownstone’s rooming-house past, a claw-footed tub occupies a corner of the parlor, showing off old jazz LPs rescued from the garbage during renovation.

Second- and third-floor guest rooms are spacious and simply furnished--radios but no TVs or telephones. The maple, oak and Peruvian walnut floors, fireplaces and alcoves with built-in cabinets add turn-of-the-century charm.

Calvo hopes that the Flophouse name--harking back to the places where jazz musicians stayed--will attract painters and other artists. He has hosted two exhibits and offers an “artist rate,” $75 versus the $90 I paid for a double. But for now he receives mainly non-artists--German, Italian, French and Scandinavian tourists as well as African American couples looking for a romantic getaway.

Demetra and I started our visit by meeting a friend, Maria, for lunch at one of my old favorites, a local coffee shop called Pan Pan, where we found her at the low Formica counter swapping astrological information with a woman seated on the next stool.

On summer days after my library research, I used to slip in here and nurse the same iced tea for hours. People don’t come to Pan Pan simply to order coffee or grits. They come in, well, to come in. Maria was happily going at a plate of salmon cakes, recommended by her new friend. Demetra and I settled on cheeseburgers and fries.

After lunch we emerged into a brisk but sunny afternoon for a self-guided walking tour. The corner outside Pan Pan is rich with pillars of Harlem society: Harlem Hospital and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, plus a historic branch of the New York Public Library and the YMCA. Demetra loved “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” and was pleased to stand before the YMCA where the civil rights leader stayed, getting a glimpse of “his view of the world.”

We headed to Striver’s Row, the nickname for the black middle-class enclave of Stanford White townhouses. Along the way we passed the home of James Weldon Johnson, author of “Lift Every Voice and Sing” (a poem and later a song that became a black national anthem of sorts), and a studio space of Harlem Renaissance photographer James Van Der Zee, who came to prominence in the 1969 show “Harlem on My Mind” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Eventually we circled back to 125th Street, Harlem’s main commercial thoroughfare. Also named Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, the street is a bustling mix of old and new. The famed Apollo Theater, where performers such as Ella Fitzgerald and “Little Stevie Wonder” performed at Amateur Night, is undergoing an 18-month renovation. (AOL Time Warner held its annual shareholders meeting here last year.) The new $65-million Harlem USA is a monstrous glass expanse that houses Old Navy, the Disney Store and Magic Johnson Theatres. And what’s brewing at the corner of Lenox Avenue, a few doors down from Bill Clinton’s office at 55 W. 125th St.? None other than Harlem’s first Starbucks.

Afternoon street life was loud and busy with hip-hop music and neon signs advertising hair braids and gold jewelry. Pungent wisps of sandalwood incense wafted from tables where piles of black history books, $1 socks, watches, CDs and videocassettes were for sale.

On Lenox Avenue near the north end of Central Park, we ducked into Harlemade--a new, bright and uncluttered bookshop that also stocked Harlem memorabilia, postcards, posters and T-shirts.

A few doors away we were drawn into Settepani, a sleek new cafe and bakery. We sipped espresso and cappuccino and shared a fruit tart as dusk set in. An elderly man clutching plastic shopping bags paced before the glass case of treats, bemoaning the fact that his diabetes forbade even a taste.

Harlem’s West Indian presence dates to World War I, and a vibrant Caribbean commercial and political life is evident today. A Guyanese restaurant called Flavored With One Love was our choice for dinner. We enjoyed delicious plates of spicy curry chicken and goat accompanied with rice and peas, string beans and chickpeas.

We found night life at the restored Lenox Lounge. It was early enough for us to land two stools at the bar, our vantage for an evening of people-watching and chatting with regulars. “This is our Cheers,” said one of our bar mates.

The next day I wanted to see Harlem through a different lens, so I selected the guidebook “Stepping Out: Nine Walks Through New York City’s Gay and Lesbian Past.”

Demetra and I concentrated on the area around historic Mount Morris Park, also known as Marcus Garvey Park. Elegant brownstones, churches and apartment buildings sit amid signposts festooned with banners announcing the neighborhood’s landmark status.

Looking for the homes of writer Hurston and Alain Locke, the so-called father of the Harlem Renaissance, we were treated to the magnificent Graham Court apartment building, the Olga Apartments and a brownstone that was home to Langston Hughes. None of these buildings is open to the public, but their exteriors--windows, stoops, columns and arches--opened our eyes to the aesthetic sense and sensibility of another era.

The art scene in Harlem today also provides a richness tied to the neighborhood’s diversity. With the remaining daylight we headed for Gallery X, a new venue showing paintings of an Iranian American artist. Antonio Pringles, who was minding the front gallery for Turkish owner Gulsun Erbil, offered to show us the studio in back.

There Erbil had spun a crazy, three-dimensional web of colors--string, glass, mirrors and spiral slivers of wood. The art sprawled around the office and into a kitchen and the loft sleeping space.

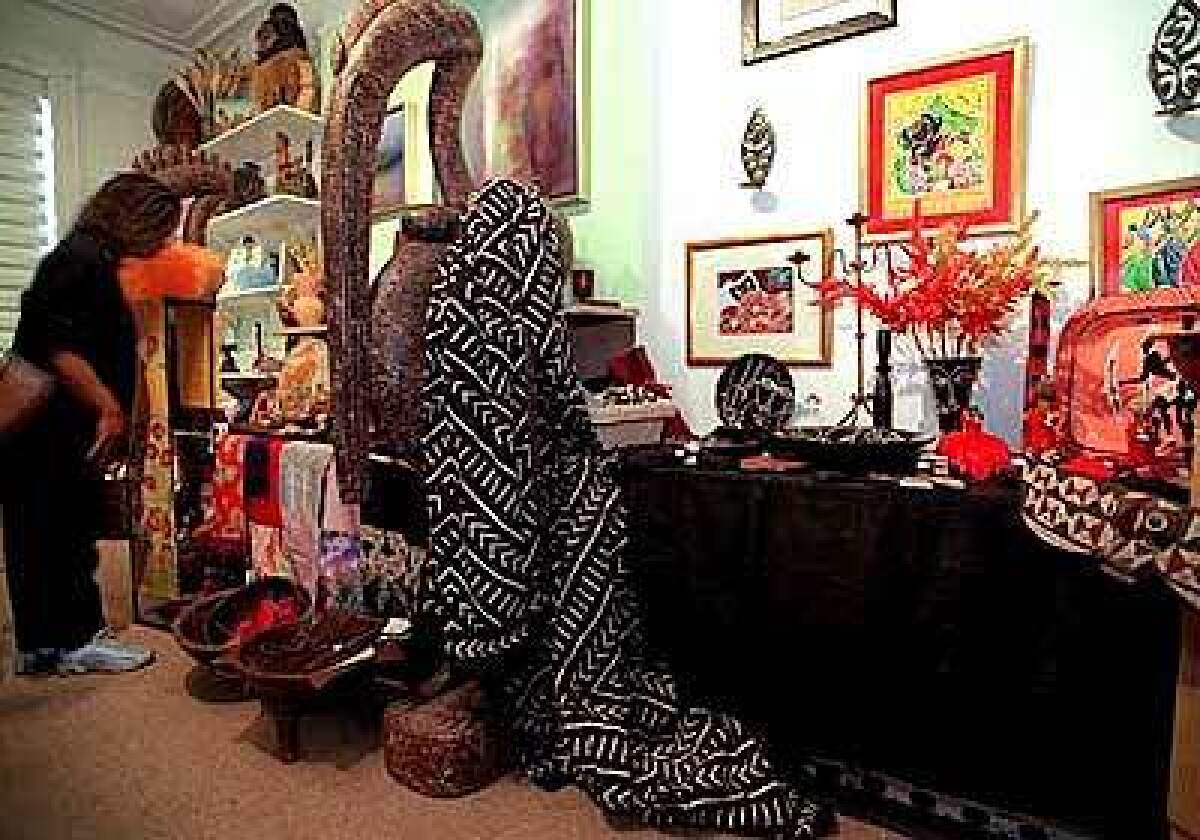

At day’s end we stumbled upon the Brownstone, another fabulous discovery. “Created by women for women,” the house is a cozy, shared commercial space. Each room offered something different: clothing, accessories, fine jewelry and art, a bridal salon, an interior design studio, even massages and facials at the Lady Sandalwood Day Spa. It added up to a funky mix.

A small tearoom on the second floor offered lunch and dinner by reservation only. Lucky to get a last-minute spot, we stayed for dinner and found ourselves seated at a silk-wrapped table. Our orders--Thai peanut chicken, cilantro-soaked whitefish, carrot-and-basil-dressed salad and sweet potato chips--were delicious.

The meal was sophisticated and elegant, two qualities we discovered again later that night at Showmans, a jazz club dating to the 1940s. The long, narrow layout made for a cozy setting when the joint reached full swing. Throaty saxophone notes played off rat-a-tat drumming and keyboard twinkles. Up and down the bar, hands clapped and heads nodded.

Demetra chatted with a Japanese couple next to us. He was in New York studying English. She was on a weekend visit. They wanted to hear good jazz, and their guidebook had led them to Harlem. Just then a tea-colored woman at the bar grabbed the hand of another Japanese tourist and pulled him to an improvised dance floor. They may not have understood each other’s words, but they settled on a language their dancing bodies knew how to speak, giving us all a glimpse of the exchange that can happen when you get off the bus.

Monique M. Taylor, a sociology professor at Occidental College in Los Angeles, is the author of a book on Harlem to be published this fall.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.