San Francisco, in Full Swing

SAN FRANCISCO — At 10 on a crisp Saturday morning, my sister Connie and I stood in our woolly socks in a cavernous former high school gym and gazed up. A silver-haired 64-year-old retired college professor in a turquoise leotard had just climbed a skinny steel ladder to a 30-foot-high ledge.

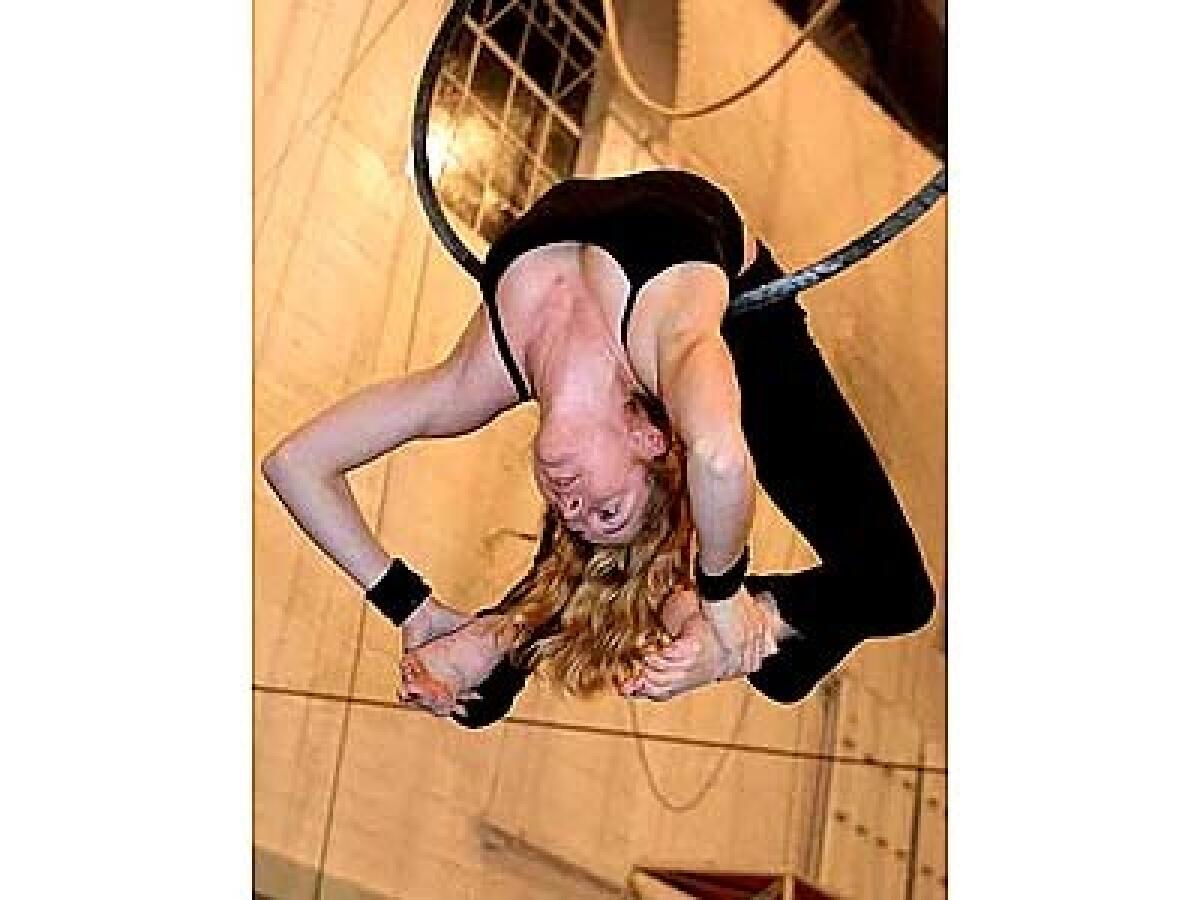

Eyes focused ahead and legs slightly bent, she grasped a gauze-covered bar with both hands. On the command of “Hep!” she swung out with a graceful arch, kicked her legs back, then brought her feet up and hung by the knees upside down, flying back and forth before dropping to the net below.

Forget skydiving, bungee jumping or hang gliding. This was the thrill I sought: the flying trapeze. This was the realm of the young at heart, a place of levity and joy--sentiments that have been all too elusive for many of us in recent months. When Connie and I walked through the door of the San Francisco School of Circus Arts that morning and read the sign, “Do Not Ride Your Unicycle in the Basement,” we knew we were in the right place.

As a girl, I found nirvana high in the treetops, hanging by my knees. I never outgrew that yearning. A circus-themed weekend in August, centered on the San Francisco trapeze classes, let me fulfill a lifelong dream while letting go of stresses and sending my spirits soaring.

The adventure began on a Friday when I flew to Oakland to meet my sister, who lives in the Bay Area. We drove to San Francisco and checked into the monolithic Hyatt Regency at Embarcadero Center ($139 per night plus tax, though rates have since dropped on some weekends).

Wired about the next day’s trapeze lesson, we skipped a fancy dinner and channeled our energy into a walk through the lively North Beach neighborhood. At Caffe Trieste we stopped for café crema and authentic Roman tomato focaccia, then watched a parade of leather-clad hipsters bop down the boulevard before we called it a night.

Harvard philosophy professor and author Sam Keen, an ardent flier who first learned trapeze arts at age 62 at the San Francisco circus school, has written about “the aerial instinct--the drive to soar above our present condition.” It’s the defining characteristic of being human, he says.

School founder Stephan Gaudreau shares the philosophy. The trapeze is a metaphor for risk, for overcoming self-imposed limits, he says. Some students use classes as a way of conquering midlife crises, shyness or phobias.

Many of the teachers are current or former members of Cirque du Soleil, Ringling Bros. and other top shows. The school also develops talents for its own professional troupe, the New Pickle Circus, which practices and performs in the same space. Classes are offered in clowning, stage combat, Chinese acrobatics and other arts. The most popular by far is the flying trapeze.

The beginners’ class is open to everyone and has no physical requirements. Surprisingly, upper body strength matters little. By the end of the 90-minute lesson, students should be able to perform a blind, upside-down flight into the arms of an instructor on a facing trapeze. Classes are limited to six and emphasize personal attention, so even the klutzy students can learn to fly.

Inside the gym we found an air of privilege, as if we had been admitted to a rarefied (albeit eclectic) club, one that included a kindergarten teacher, a waitress, a physical therapist and a stockbroker. After we had practiced with instructor Scott Cameron on what is called a static trapeze on the ground, Connie and I were eager for flight.

She ascended to the platform first, where a lithe instructor named Eric Vuillemey attached safety lines to her belt and assisted with takeoff. (The lines, held by another instructor on the ground, resemble the belaying ropes used in rock climbing.) In the air--as when earthbound--Connie demonstrated a dexterity that put me to shame when my turn came.

At the top of the platform, I grasped the bar. Then everything happened as if I were in a trance. With Eric’s loud “Hep!” I swung out. The whoosh of air in my ears seemed to whisper “welcome.” With the deepest pleasure, I was flying.

Timing was essential. My takeoff and back arch got better after a few tries. I managed to curl up my feet for the knee hang with ease, and it took only two tries to perfect my upside-down drop.

But when instructor Jennings McCown climbed hand over hand up the rope, wrapped his Superman legs around his trapeze and began to arc toward me with outstretched arms, my concentration took a nosedive.

He called “Hep!” That was my cue to take off from the opposing platform, hang upside-down and meet him midway, where he would grasp my wrists and I would let go of my bar. This was the idea, anyway.

The first two attempts, I was late; our movements wouldn’t synchronize. Third try, we touched hands, but my knees would not cooperate. I was too scared to let go.

The connection trapeze artists make is as much mental as physical. I stood on the platform, took a deep breath and reminded myself I had to trust Jennings. On my last try, I got the timing right--barely--and released into his arms.

Connie and I were still giddy after class. We changed clothes at the hotel and strolled over to--where else?--the Original Clown Alley on Columbus Avenue for sloppy Clown Burgers and strawberry shakes. After 40 years, this joint is still popular with lawyers and bankers from the Financial District. Former owner Enrico Banducci, inspired by the clientele, named the restaurant for the under-the-grandstand area of the circus where clowns gather before entering the ring.

After lunch we detoured along the waterfront, where a dazzling white tent with streaming flags caught my eye. This was Teatro Zinzanni, billed as “Love, Chaos and Dinner.” Translation: a dinner-theater spectacle of circus acrobats, illusionists, musicians and other performers. Held in one of the few remaining handcrafted traveling tents from 1920s Europe, the show is Moulin Rouge in style. A five-course meal is included in the hefty price, which starts at $99.

It would have been an ideal cap to the day. Alas, the show was booked for a corporate affair that night. But next time, next time. (Connie has since seen the show and thought the performers were interesting and the setting much more intimate than she expected.)

We spent the rest of Saturday afternoon at the Musée Mécanique, our curiosity having been tweaked by a description in the guidebook “San Francisco Bizarro.” Hidden in the basement of the tourist-trap Cliff House restaurant on Point Lobos Avenue, this privately owned museum houses one of the world’s largest collections of working antique arcade games: 140 in all, 25 cents a pop each. They ranged from the hilarious (the How Hot Are You? Love-o-Meter) to the grotesque (the French Guillotine, featuring a mechanized executioner).

After watching chattering kids go mute at the sight of Laughing Sal, a towering, gap-toothed doll that greets visitors at the door with maniacal cackles, we looked over the ruins of Playland at the Beach. Powerful waves washed over the once-lively 1914 amusement park where many of the machines were originally installed.

A Vietnamese dinner followed at venerable Thanh Long, my sister’s favorite San Francisco restaurant, where the “secret-recipe” garlic noodles and roasted crab were fantastic. Opened in 1971, Thanh Long is the more casual predecessor of the chic Crustacean restaurants in Beverly Hills and San Francisco, all still owned and operated by three generations of An family women. Without a reservation, we waited 30 minutes, but it was worth it. Just the thought of those noodles still makes my mouth water.

Sunday morning, Connie and I grabbed a bench at Red’s Java House, a funky Embarcadero landmark crowded with construction workers, sailors and J. Crew prepsters. A good cuppa joe and sugar doughnuts--real sinkers--opened our bleary eyes.

Before my plane, we drove a few minutes south on Interstate 280 to the rolling hills of Colma and a curious monument at Olivet Memorial Park cemetery. Erected in 1945 by Showfolks of America, a national organization of circus performers, a memorial salutes big-top professionals “so that they might rest in peace among their own.”

The marker is hard to miss: Amid shady manicured grounds, a smiling, bright yellow clown points to the resting place of Swacko, Bunny Bunting and dozens of other troupers.

At the airport I mused about our aerial escapades. Most important wasn’t the trapeze trick we accomplished but what grew within us during flight: a little more faith in others, a little more trust in ourselves. And keeping a smile on my face was the golden rule of circus school: Do not ride your unicycle in the basement.

Lisa Marlowe is a freelance writer based in Malibu.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.